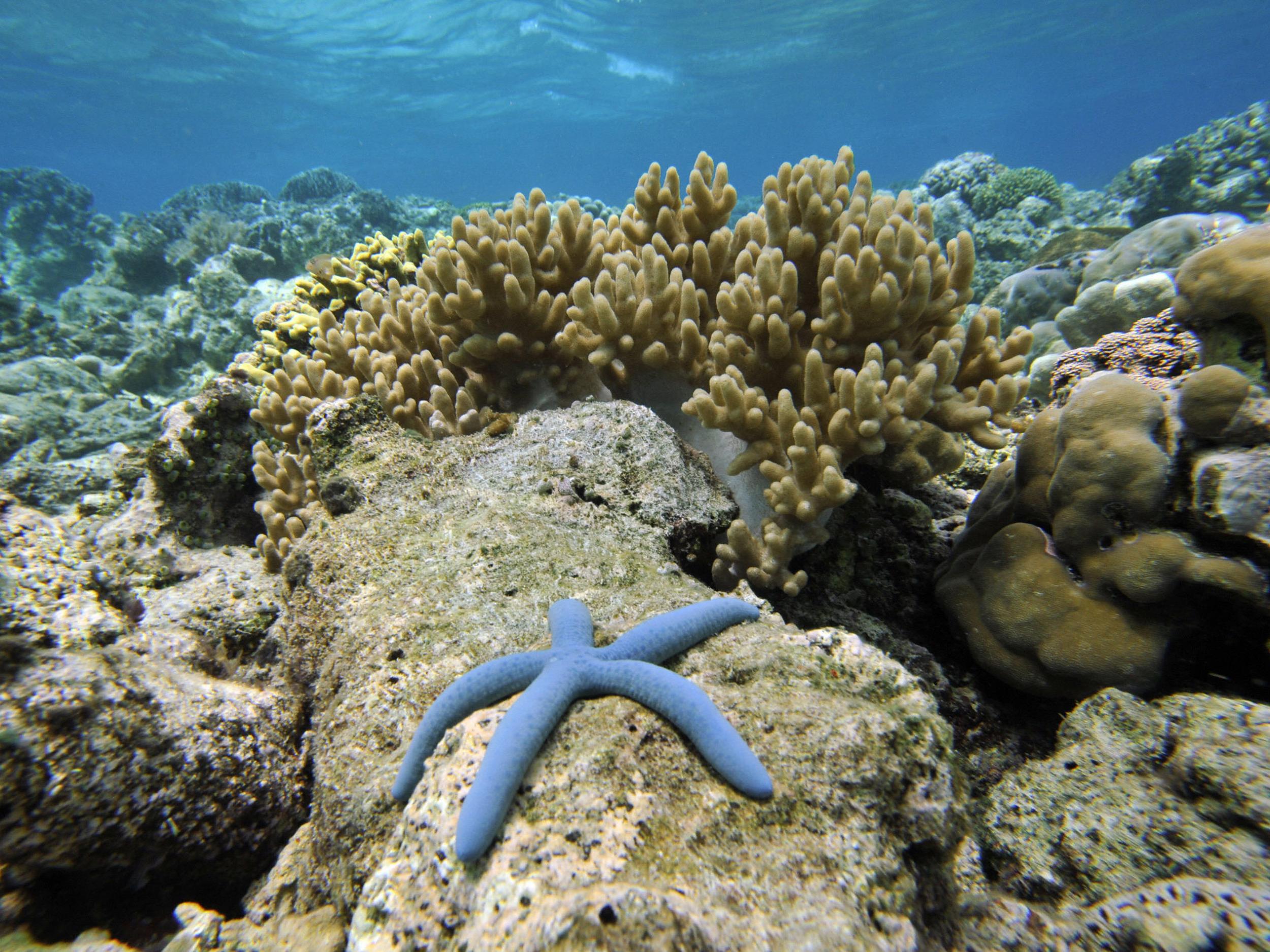

First genetically engineered coral created to help save reefs from climate change

New technique holds promise for understanding genes that protect corals from rising temperatures

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Genetically engineered coral has been created by a team at America’s prestigious Stanford University, in a project they hope will serve as a “blueprint” for future coral conservation.

For the first time, researchers were able to apply a unique tool called CRISPR-Cas9 to edit coral genes.

In the future they hope to identify genes involved in coral survival, especially those that help them tolerate the rising temperatures that have led to catastrophic reef “die-offs”.

While scientists have emphasised that genetically enhanced “super-corals” are still a long way from becoming reality, this work is still thought to hold great promise for coral protection.

“We hope that future experiments using CRISPR-Cas9 will help us develop a better understanding of basic coral biology that we then can apply to predict – and perhaps ameliorate – what’s going to happen in the future due to a changing climate,” explained Dr Phillip Cleve, a geneticist and the lead author of the new study.

CRISPR-Cas9 has become the biologist’s go-to gene-editing tool in recent years, but it has proved difficult to apply it to corals due to the way they reproduce.

Corals breed only once or twice a year in a process initiated by the appearance of a full moon. They eject huge quantities of eggs and sperm into the ocean, which mix freely and fertilise each other.

During this period, scientists have a narrow window of opportunity to perform gene editing when the egg and sperm have just met, but before the newly formed embryos start dividing.

Retrieving newly fertilised coral eggs from the sea is difficult, but Dr Cleve worked with a team of reef experts from Australia who understood the rhythms of coral reproduction.

Together they obtained enough samples to experiment with, and proceeded to modify three genes in a proof-of-principle study that they hope will help scientists understand and conserve corals more effectively.

Their results were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The new research comes at a time of great concern for the world’s coral. Heatwaves wiped out nearly a third of the Great Barrier Reef’s corals in 2016, as the rising temperatures caused them to bleach.

Coral bleaching is a phenomenon that is inextricably tied with climate change, as it involves high sea temperatures causing stressed corals to expel the algae they rely on for survival.

In light of these events, coral researchers have emphasised the need for “radical interventions” if the world’s reefs are to be saved.

Proposed measures have included geoengineering the atmosphere to cool the reefs down, and genetic modification of corals to make them more resilient to climate change.

Australian researchers have already examined the feasibility of “assisted evolution” – creating hybrid species or selectively breeding to produce strains that can tolerate warmer temperatures.

Other research has explored the idea of genetically engineering the algae that live in close association with corals to make them more heat-resistant.

Dr Cleves said he wanted to see other groups developing on this early work and potentially knocking out genes involved in the bleaching response.

“I want this paper to provide an early blueprint of the types of genetic manipulations that scientists can start doing with corals,” he said.

However, coral expert Professor Jorg Wiedenmann from the University of Southampton – who was not involved in the study – warned that this was not all about creating “super-corals”.

“The current paper is to an extent a breakthrough because that really allows us now to manipulate these systems and see if one particular gene or gene product is really responsible for heat tolerance,” he told The Independent.

“But we are a very long step away from generating ‘super-coral’ that can turn the fate of the coral reefs around.”

Dr Cleve agreed that for the time being the goal of applying genetic techniques to corals is to understand how these creatures work, and why they respond in certain ways to the changing climate.

“Maybe there are natural gene variants in coral that bolster their ability to survive in warmer waters; we’d want to know that,” he explained, describing the current situation in coral research as “an all-hands-on-deck moment”.

Professor Wiedenmann said that while gene editing is likely to prove a highly useful tool, scientists must not lose light of the bigger picture when considering coral conservation.

“We really need to focus on keeping the reef environments habitable for corals,” he said. “That has to be done by reducing the emissions of greenhouse gases to slow down the warming process and looking after reefs at the local scales.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments