Why 3D printing coral reefs won’t save our oceans

Since the 1980s, tropical marine habitats have suffered large-scale destruction as a consequence overfishing, pollution and climate change – but simply replacing them with modern technology is no miracle solution

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Coral reefs are vanishing from the world’s oceans. At least three quarters of these tropical marine habitats are severely threatened globally and in 2016 alone, the Great Barrier Reef lost up to 30 per cent of its coral cover. But could modern technology simply create more reef? It may sound fantastical, but scientists are working on 3D printing new reef habitats to replace those lost from climate change, overfishing and pollution.

Coral reefs are important ecosystems for people in tropical countries as the sea life which lives on them is a major source of food and income. They also protect shorelines from erosion and storms.

Unfortunately, overfishing, pollution and climate change have changed how most coral reefs look and function. Corals are particularly sensitive to small increases in sea temperature and so highly vulnerable to global warming. Since the 1980s, many reefs have suffered large-scale coral die-offs as a consequence of high temperatures.

Managing the reef

When corals die, the hard structure of the reef still remains behind and can be colonised by new corals. But this process of recovery can take a long time, particularly if the environmental problems have not been effectively managed. This means there is actually plenty of existing reef structure, but much of what is left is now devoid of corals.

Corals are a bit like trees in a forest – they create most of the complex structure that provides a habitat for a diverse range of species.

Most efforts to manage impacts on coral reef ecosystems have focused on establishing and setting up marine protected areas (MPAs), which are regions of the ocean where fishing and other activities are restricted or banned. At least a third of coral reefs are already inside MPAs and, if effectively managed, these provide huge benefits including protecting fish and other vulnerable species, limiting other practices that cause pollution or direct damage.

However, in some cases, even well managed and protected reefs show little recovery due to a poor supply of new corals. These arrive as small larvae carried by currents and use the reef to settle and metamorphose. Sometimes the reef surface has been reduced to rubble and is no longer stable enough to support growing corals, usually due to dynamite fishing or ship groundings. Reefs within protected areas are also not shielded from the effects of global climate change.

To address this, researchers have looked at how to restore degraded reefs, either by directly planting corals onto reefs, or more rarely, repairing or replacing parts of the reef with human-made structures.

Restoring the reef’s function as a habitat for wildlife has been attempted in numerous places around the world, often with limited success and usually at very small scales of tens to hundreds of square metres. In many cases, restoration efforts fail to deliver results because the factors that caused a decline in the first place have not been adequately managed. In other cases, the reasons for restoration are not carefully thought through, making it hard to judge if a project has been successful or not.

3D printing a reef

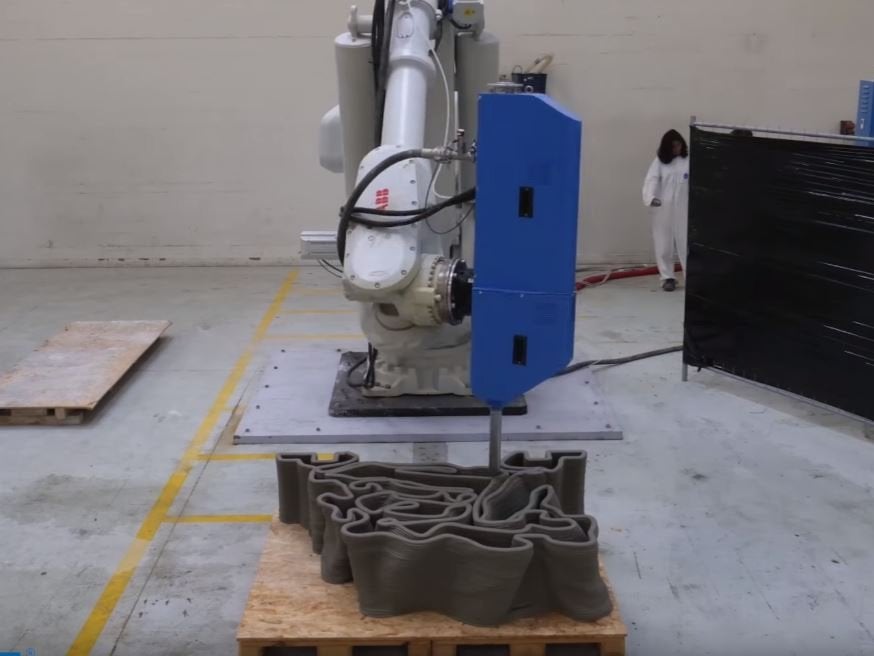

Recently, one the largest 3D printed coral reef was deployed at a site in the Maldives, as a way of creating new reef habitat, using a new technology called Modular Artificial Reef Structures, or Mars for short. Mars consist of lattices that have been 3D printed in ceramic material and designed to be deployed from small boats and pieced together by divers. The idea is that they can be used together with coral farming – where coral is cultivated for commercial purposes or reef restoration – to create new reef habitat in areas that have been degraded or where there were no corals to begin with, such as sandy bottoms.

The potential benefit of modular structures like Mars is that they don’t require heavy-duty machinery to deploy (for example, cranes and barges are needed to deploy large concrete structures), so can be used in remote locations to create artificial reefs at lower cost. Another advantage is that 3D printing technology allows you to make structures that actually look like reefs and have complex structures to create a range of habitat types for fish, corals and other reef organisms.

The system can also be tailored depending on the specific restoration goal in a given location. Each of the units is 3D printed and moulded, with hollow pieces filled with marine concrete and steel reinforcement to aid durability.

The surface design allows for corals to be easily transplanted using epoxy or a similar adhesive and the surface is chemically inert, so it is thought not to harm newly-attached corals and coral settlers.

Artificial reef structures such as these may create value at small scales by providing high value dive sites to tourists when natural dive sites have been degraded. They also provide a way of involving tourists and volunteers in conservation efforts if they can be engaged as volunteers to help construct reefs and transplant corals.

Aid not a cure

Much of the value of reefs comes from them having live corals, for example, many tourists prefer to see living rather than dead corals. Living corals continue to build reef. So without sufficient numbers of living corals, the actual reef structure will eventually erode over time and will not grow to keep up with sea level rises. Reefs need growing, healthy corals to continue to function and protect coastlines. So merely increasing the amount of reef structure available for coral growth will not in itself solve the problem of natural reef decline.

Another big concern with using artificial structures as a restoration tool is that they are very expensive and may therefore divert funds from existing proven conservation techniques (for example, policing within marine protected areas). It should also be mentioned that artificial reefs may not necessarily have the same levels and types of biodiversity as natural reefs. The biggest problem with artificial reefs, however, is that these methods cannot be scaled up to anything like that required to counter the current degradation on reefs.

This does not mean that 3D printed reefs cannot be beneficial in coral management as any restoration activity can provide an opportunity to engage the public to learn more about the difficulties facing coral reefs. However, the only way to tackle reef decline in the long term, is to deal head on with its main causes: climate change, pollution and destructive fishing practices.

James Guest is a research fellow, Adriana Humanes is a postdoctoral researcher, and Alasdair Edwards and John Bythell are professors of coral reef ecology at Newcastle University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments