Behind the scenes at Cop28 with a negotiator whose nation’s survival is on the line

Louise Boyle spends a day at the global climate summit with Tina Stege, climate envoy for the Marshall Islands, who came to Dubai with a very important mission

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s 6.45am, and the first rays are filtering through the morning smog, the sign of another scorching day in Dubai.

Tina Stege, climate envoy for the Marshall Islands, is on the metro headed for the Cop28 climate summit, and in desperate need of a cup of tea. Last night she left Expo City, where the two-week event is being held, after 9pm.

“It’s a lot of late nights and early mornings,” she told The Independent.

Stege is one of thousands of representatives and negotiators from 196 countries who speak for their national interests at the annual conference under one overarching goal: limiting the global temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius, or “well below” 2C, beyond which scientists say Earth faces irreversible tipping points.

Stege grew up in Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands, and attended Princeton University where she studied the legacy of nuclear testing by the United States on her homeland. After working in the Marshall Islands foreign affairs ministry and at a series of NGOs, she was appointed as climate envoy in 2018, representing the country’s interests from New York.

Now at Cop28, her first commitment at 8am is a closed-door coordination with the Alliance of Small Island States, and she heads inside with a tea, finally, in hand.

AOSIS (Ay-Oh-Sis, per one of the climate world’s many, many acronyms) is a group of countries from the Caribbean, Pacific and South China Sea who negotiate together to give them more clout because, as their website explains, they are “small, remote, vulnerable”.

While no nation is immune to the worsening climate crisis, the Marshall Islands faces urgent, existential threats.

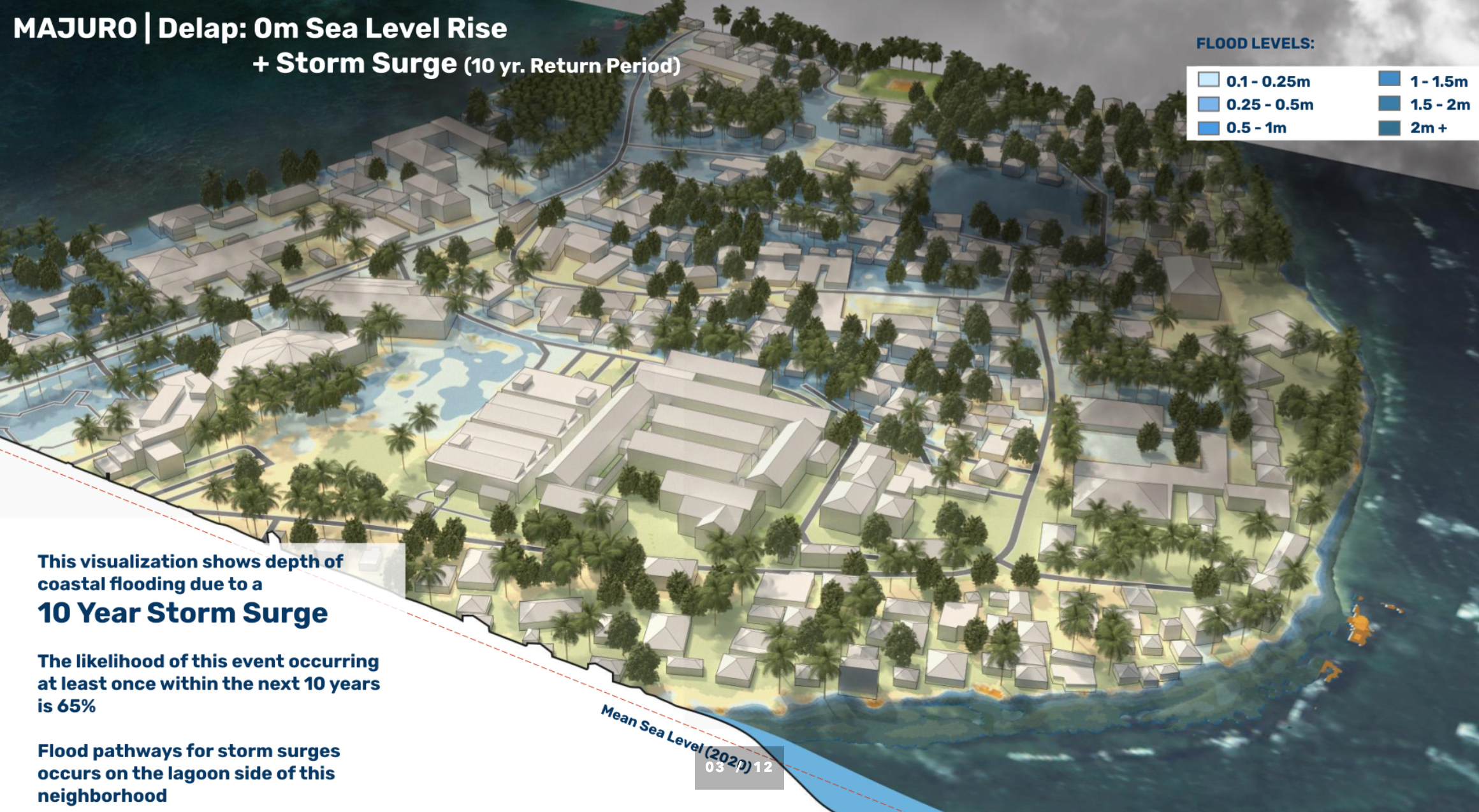

Halfway between Hawaii and Australia in the Pacific, the nation of coral atolls is only 7 feet (2 metres) above sea level at its highest point. Around 60,000 Marshallese live in an area equivalent in size to Washington DC, surrounded by 77,000 square miles of ocean territory.

The projected one-metre sea level rise in the coming decades would permanently flood 40 per cent of buildings in Majuro and see some islands disappear beneath the water, according to a 2021 World Bank study.

Even greater sea level rise - not out of the question if governments fail to rein in global heating - threatens the country’s very survival.

The Marshall Islands has done little to cause these impacts since it is responsible for only a minuscule amount of total global carbon emissions.

The injustice of this predicament led the country to form the “High Ambition Coalition” (HAC) ahead of the 2015 Paris negotiations, and is one of the strongest voices demanding the lower target - often chanted as “1.5 to stay live”.

Their demand that developed, rich countries work harder, and faster, to cut the fossil fuel reliance that is causing them so much harm, is what Stege, and the rest of the 40-strong Marshallese delegation, are battling for at Cop28.

“Below 2C does not cut it,” Stege told The Independent. “Those on the frontlines will not be able to adapt.”

“All our future will hold is loss and damage, past 1.5C. This is why we continue to fight, and never give up,” she said.

At the Dubai summit, the Marshall Islands’ demand to “phase out” fossil fuels gathered pace with more than 100 countries joining the call for this outcome.

While negotiations are fraught and the final agreement remains far from consensus, there was for the first time a real possibility that the world will call time on the fossil fuel era. And for Stege, the responsibility she feels when in these meetings is deeply personal.

Much of her family remains in the Marshall Islands. “My mom, dad, brother, and his kids,” she explained between meetings. “We grow up with an extended family and a lot of cousins who are like brothers and sisters are still there.” But other relatives have moved to the US. (A government pact allows unrestricted migration by the Marshallese in exchange for America using the islands as a Pacific military base.)

It’s estimated that one-third of Marshallese have left to seek jobs and escape climate impacts, not only sea level rise but increased droughts, heatwaves and saltwater intrusion in the past five years,according to research.

When Stege returns to the Marshall Islands with her children, she notices that beaches where she played growing up have vanished. Water wells, used for cooking and washing, are now brackish. “My brother lives on land where it’s very low and when the tides are really high, the water comes right up,” she says.

After an hour of the AOSIS meeting, the doors open, and delegates peel off in different directions. Stege makes a beeline for a quiet corner. She has been constantly texting with other countries’ delegations, to shore up support for the fossil fuel phase-out demand.

In between official events, she has seized the opportunity for a “bi-lat” with the Netherlands - negotiator-speak for a meeting between representatives of two countries. (The Netherlands is a HAC member.)

“I have always called him ‘Jaime’,” Stege said. “For the longest time, I didn’t know he was a Royal Highness.”

Minutes later, the low-key Prince Jaime de Bourbon de Parme, Netherlands’ climate envoy, greets Stege warmly. For the next 20 minutes, she explains their key issues and then he updates her on the Dutch strategy to address fossil fuel subsidies (plans potentially in jeopardy after the recent election victory of right-wing populist Geert Wilders).

Stege’s next meeting is across the sprawling venue, and requires speed-walking under the baking sun. Despite confessing a bad sense of direction, she makes it to the French pavilion with few wrong turns.

Inside the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA) have gathered - a group of two dozen countries and states, which pledged to end their domestic oil and gas production and are among the most strident on “phasing out” fossil fuels.

The discussion centers around new members - Spain, Kenya and Samoa - who will be announced at a press conference later in the day. The alliance is also joined by former US vice president and longtime climate activist, Al Gore, who offers words of encouragement.

Despite fossil fuels being the root cause of the climate crisis, mention of them first appeared in a final Cop agreement two years ago in Glasgow (and then, only coal).

A swift lunch of shakshuka follows while Stege talks strategy with an advisor and makes phone calls to check up on a colleague who has been briefly hospitalised in Dubai.

Then it’s on to the Moana Blue Pacific Pavilion, where the Marshall Islands are launching their National Adaptation Plan after five years of work.

The delegation has dressed in matching shirts and dresses along with traditional amimono, handwoven handicrafts from shells and coconut fronds, as a sign of unity.

The plan is titled Papjelmae in the Marshallese language, which loosely translates as preparing for the future. It is a sobering look at what the coming decades will hold there.

“We call it our national adaptation plan, but it is really our survival plan,” says John M. Silk, Minister of Natural Resources and Commerce, and head of delegation.

The plan requires billions of dollars in the coming years to build seawalls, protect freshwater supplies, relocate residents and elevate the land.

Hundreds of people across the islands, which each have a unique identity, were interviewed for the plan about what matters most to them - fears over loss of livelihoods, education, freedoms, and opportunity.

The resounding message was that forced migration would be intolerable, and that people want to remain in the Marshall Islands.

“I don’t want to leave my country,” Mannley Compass, one of the youth delegates, said.

In the late afternoon, Stege is on the move again to one of the large plenary halls where Cop28’s most high-profile events take place, for the BOGA announcement.

With ten minutes to spare, she and a few colleagues take advantage of refreshments on offer - chocolate-covered dates, petit fours (and more tea).

Simon Stiell, executive secretary of the UNFCCC which oversees Cops, waves to Stege as he races past, quickly followed by Selwin Hart, Barbados’ former climate negotiator and special adviser on climate action to Secretary General Antonio Guterres who calls that he will see her at the Powering Past Coal Alliance event, where both have been scheduled to speak. She replies that she will be asking the countries to go further than “powering past coal”.

At the “BOGA” event, Stege joins representatives from Denmark, Ireland, Chile, Samoa and Spain on stage.

When asked by a journalist if Cop28 will be a success without a final agreement calling for fossil fuel phase out, they give a resounding “no”.

As everyone moves off, Stege grabs a moment with Chile’s environment minister Maisa Rojas to coordinate another “bi-lat”.

Rojas plays a key role in Cop28 as one of a ministerial pairing (with Australia) who have responsibility for finding consensus among countries over tricky issues when the clock ticks down to a final agreement.

Outside, the evening has cooled and Stege makes it to the UK pavillion for the coal event with five minutes to spare - giving her just enough time to glance over remarks on her tablet.

While the Marshall Islands has no coal power, it has joined the group in support of those that are working towards ridding their economies of the dirtiest of fossil fuels.

At the event, she listens as David Turk, deputy to US climate envoy John Kerry, speaks on the US decision to join the alliance. Then it’s Stege’s turn.

“We support the PPCA in saying ‘no new coal’” she says. “But we also say ‘no new oil’ and ‘no new gas’.”

At 8pm, she regroups with Hart to return to the main negotiations on the other side of the venue which are expected to go late into the night. “It’s a long walk,” she tells him.

Before leaving, she recalled a moment at the beginning of Cop28 which managed to stop her in her tracks.

“On my very first day, I was walking to a meeting room and passed this gallery of photos from across the world. I passed, and thought ‘wait a minute’ and I went back. It was my Bubu Tejja, who I just spent time with over the summer. She was right there.”

Stege had seen a photo of Theresa de Brun, her great-aunt, who she refers to as “bubu”, or grandma, in Marshallese which is part of an exhibition inside the Cop venue, “Loss and Damage in Focus”. It features Ms de Brun in her wheelchair with her arms around her grandchildren on the remote outer island of Likiep.

“The Marshallese woman has seen a lot of changes happen to her island over the past 86 years,” the caption reads.

“She’s noticed that the climate has been getting dryer and hotter. Because of a nine month dry spell, her grandchildren experience more hunger than she did due to less food being produced.

“She also recalls the backside of her house being covered by trees, preventing her from seeing the lagoon. Today, she sits in her wheelchair with her grandchildren and gone are all the trees and beaches that have eroded away. Instead, all that’s left is her seawall, which protects her land from further erosion, and a perfectly clear view across the lagoon.”

The final day of Cop28 negiotations stretches into the early morning — but while the days are long, Stege is all too aware of how short the coming years will be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments