The melting of the world’s ‘third pole’ is a looming climate disaster – so why aren’t we taking about it?

The vast Hindu Kush-Himalaya ice sheet contains the world’s largest amount of snow and ice, after the Arctic and Antarctic. Amy Coles explains that without a major reduction in global emissions, it could be a fraction of the size within decades - changing the lives of the hundreds of millions who rely on it

Ask anyone what’s happening in the North and South pole and they will tell you the ice caps are melting. Probe a little further and they might tell you it’s the result of runaway climate change, and, at some point in the near future, sea levels will rise and low-lying places like Florida and Venice will disappear.

It’s a familiar, if bleak, scenario, well known to most regardless if you follow climate science or not.

But ask the same person about the world’s ‘Third Pole’ and they will likely give you a bemused look, which is frightening because it’s the site of another, perhaps even more urgent, climate emergency, that will likely make life impossible for up to a fifth of the world’s population within our lifetime.

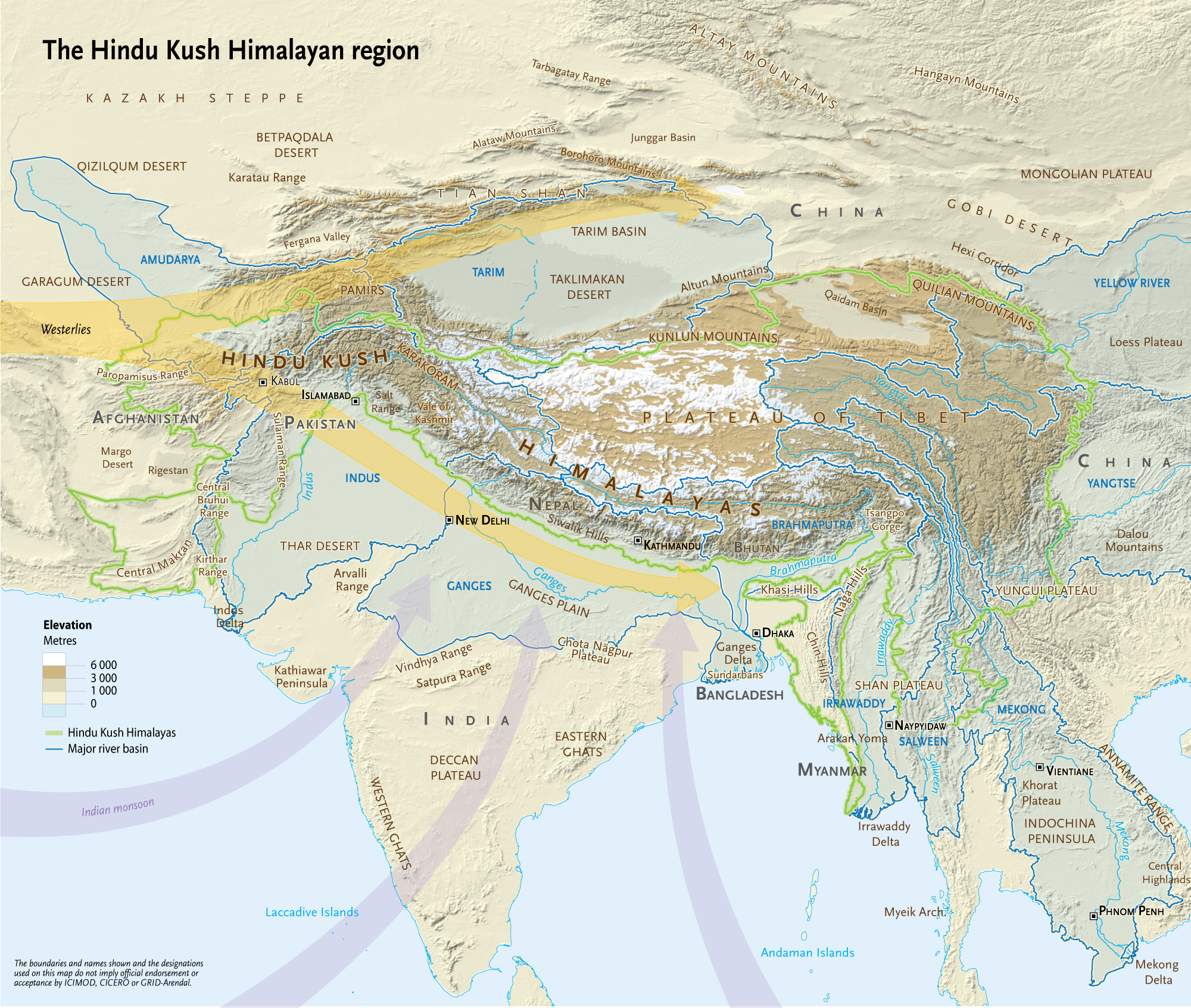

The third pole is the name given to the 1,200-mile-long Hindu Kush-Himalaya (HKH) mountain range. Stretching across eight countries in central Asia, the area is home to 10 major river basins and some of the world’s highest mountain peaks, including Mount Everest. It’s also where you will find the third largest amount of ice and snow in the world outside of the Arctic and Antarctic thanks to the 9,000 glaciers found there.

These remote glaciers are a lifeline for at least 240 million people who live in the peaks and valleys of this mountain range, and who depend on the cyclical winter freezing and summer thawing of the ice caps. Known as nature’s ‘water towers’, glaciers hold frozen snow collected over the winter months, melting slowly across spring and summer to release a steady, dependable flow of fresh water into streams that feed into rivers downstream covering hundreds of miles.

In the HKH region these mountain ranges feed the 10 largest river systems in Asia, which bring water to 1.65 billion in lowlands across Tibet, China, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh - countries that all likely to be most severely impacted by the effects of global warming.

A vital lifeline then, that the majority of Asia, depends on. Yet the first comprehensive studies of the area from last year paints a devastating future.

Scientists found that the melting rate has doubled since 2000, with over a quarter of ice lost in the last four decades after they compared spy satellite images from the mid-1970s were compared to the latest . Another landmark report published in February 2019 found that at least a third of the ice in HKH region will be gone by the end of the century – even if action is taken to drastically reduce global emissions.

If it isn’t, two thirds will be lost.

All signs point towards a chaotic and unstable future for the region – with water security likely to be a thing of the past.

Glaciologist Prof Jemma Wadham, at the University of Bristol, said: “This is a crisis that had perhaps been more hidden from the global public eye until recently.

“There have always been many isolated studies across the HKH but few integrated cross-HKH reports which raise awareness and help people understand what is going on – that’s changing now.

Two thirds of the ice in HKH region will be gone by the end of the century without a major reduction in global emissions

“Part of the issue with producing a coherent picture of what is going on is that we are talking about a 2,000km wide mountain belt, which holds over 9,000 glaciers and spans eight nations that are all rather different politically, economically and culturally.”

Scientists have projected melting glaciers will become more unpredictable, increasing river flows and the risk of serious flooding that could threaten whole communities.

After this meltwater will decrease, leading to more droughts, particularly in central Asia where the Indus River – one of the continent’s longest - expected to be among the worst hit.

Of course these are estimates. Much of the region’s future depends on the Paris Agreement pledge to cut emissions to zero by 2050 to keep warming to within the 1.5C guardrail, a target that many experts agree is looking increasingly out of reach.

Not to mention, evidence suggests mountain regions are warming at much higher rate than the global average. In a worst case scenario, huge swathes of Asia could become inhabitable without the glaciers.

For Prof Wadham, focus should now move to finding solutions to help people withstand the crisis.

She said: “Predicting what is going to happen is hard, mitigating against it is even harder.

“For the mountain communities of the HKH, some reduced streamflow in rivers later in the 21st century due to glacier loss is inevitable now, so we need to think about how to adapt.”

Climate change has already complicated life for those living closest, who were once able to predict the freezing and thawing of the village glacier with precision.

Now, the glaciers are shrinking and retreating, there are droughts, or in some cases unpredictable flooding when the glaciers melt too fast. Weather patterns are changing. The yearly monsoon, which is responsible for bringing rains that turn to snow up in the highest peaks, has weakened - starving the glaciers further and making it impossible for farmers who need the springtime water to plant crops.

In the Himalayan region there will be complete and utter crop failure at some point

Dr Duncan Quincey, Glaciologist and Associate Professor in Geomorphology in the School of Geography, University of Leeds, has been studying the region for the last 15 years.

He said: “These glaciers are not so much in the public spotlight because the impact in the western world is not very obvious.

“If there’s a flood or a drought there in south Asia why would people in the UK care about that, unless they particularly care about the environment.”

The lack of public outrage and knowledge when you compare it to the situation in the Arctic makes less sense when you consider how immediate this crisis is likely to be.

Dr Quincey said: “The issue here is much more direct and tangible than perhaps the risks associated with sea level rise from the big sheets in the poles.

“The third pole crisis will be much more immediate.

“We can adapt to the changes in the big ice sheets. We can map the low lying lands areas that will be lost and people can be moved from those areas.

“Instead, in the Himalayan region there will be complete and utter crop failure at some point.

“This could be followed in the next season by a glacial lake flooding and going down into the valleys.

“This crisis is more immediate and its effects will be completely without warning.

“People won’t have the time to adapt to the impact of rain wiping out one village or flooded plains downstream threatening food security for the entire region.”

He has been working with a team on a project called EverDrill to measure the temperature inside some of the glaciers to build a picture of how vulnerable they are to warming. The coldest temperature internal sensors have picked up over the last few years is minus 3.3C.

“It really opens your eyes to how close these glaciers are to a massive recessional phase,” he said.

Part of the challenge for protecting this area is the lack of climate science to build a full picture of its current state. As little as a decade ago, there were hardly any studies being carried out in part due to the hazardousness of the terrain.

However, both Dr Quincey and Prof Wadham are hopeful for the future. They say the significant work undertaken in the region in recent years could help the area adapt to the long-term reality and also help improve public awareness.

Prof Wadham said: “I would say that over the past few decades public perception of the crisis has been lower than perhaps in polar regions (ie the ice sheets) but that is changing now, helped by the increasing use of satellite data to gather information across such a vast region, and some landmark reports which have brilliantly synthesised a wealth of data on glacier retreat and water resources for the whole of the HKH and pulled it altogether in one place.”

She added: “Knowledge of glacier change and water resource issues in this region requires understanding of the complex natural, political, economic and cultural backdrop. What is a problem in one place, may not be in another.

“This means that any solutions or adaptations need to be effective, adaptable and cognisant of the human context. In many ways, they need to start with the people and then build out from there.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments