Climate change: Should we sue politicians for crimes against humanity?

Amid mass die-ins, no-fly movements and Greta Thunberg sailing the climate emergency message across the Atlantic, there’s one route for tackling climate change we haven’t pursued, writes Jane Fae: through the courts

When we think about climate change, the headlines are all about the damage hurtling down the track towards us: the consequences and, sometimes, the difficulties of putting a solution in place. Technical difficulties. Financial difficulties. Political difficulties.

We treat these last as though they are as much a fact of nature as the damage wrought by a warming climate. Increasingly, though, serious jurists and campaigners are beginning to ask whether those who stand in the way of reform, of repairing our climate, should be considered culpable for their actions – and criminally culpable at that.

In short, is the time coming for coordinated international action against those who, for all sorts of reasons, do not just stand in the way of measures to mitigate damage, but actively promote damaging policies? How should we treat those who benefit the climate apathy of their leaders while simultaneously decrying the systems that keep returning them to power?

“Not OUR fault!” proclaim some of the nicest of nice people – ourselves included. But, as Extinction Rebellion and David Attenborough tell us, this is an emergency, so aren’t legal repercussions inevitable?

Is it so eccentric or extreme? From where we stand today, perhaps. From banning smoking in public to exiting the EU without a deal, how quickly yesterday’s outlandish becomes the commonplace of today.

In fact, the idea of taking action against climate change deniers is not new. One of the first to do so was climate scientist James Hansen, who argued powerfully in 2008 for fossil fuel CEOs to be tried for “high crimes against humanity”.

Governments have violated the youngest generation’s constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property, as well as failed to protect essential public trust resources

Dismissing this as “political theatre and not legal scholarship”, two legal experts, Professors Charles Moellenberg and Leon DeJulius, responded by locating the issue firmly in the realm of freedom of speech. They argued that the alleged crime was no more than the “promotion of a minority, although honest, view in an unsettled debate”.

After my own brief outing on national television to discuss this idea, I was assailed on Twitter by a small army of free speech enthusiasts. Climate change is a debate like any other, so perhaps this free speech-ism is inevitable, given how the climate crisis has evolved.

Over the years I have written a lot on the topic, particularly on the consequences and implications of climate change for business.

I’ve looked extensively at renewables and their economic feasibility, the usefulness of transnational networks, examined a whole host of smart technologies, from smart homes to smart grids. We also took the measure of initiatives to make decarbonisation commercially viable through carbon emissions trading and taxes.

I learnt, courtesy of the IPCC, how concentrations of atmospheric CO2 had soared, from 277ppm in 1750 to approximately 386ppm in 2010 (and today, less than 10 years later, we have breached 415ppm: a level not seen in more than 3 million years – and never in all the time that humans have existed on this planet).

Even back then, the enormity of what humanity was doing was impressive – but not in a good way. Larger reports put together by the IPCC and economist Nicholas Stern predicted varying degrees of apocalypse. What happens if the global temperature rises by 2C, 4C, 6C... even, as one forecast had it, 17C? (Clue: we’ll be looking for a new planet.)

Meanwhile, the Association of Small Island States pluckily stood firm against global incompetence. They highlighted that those who refused to adhere to calls for action benefited the most from climate degradation, while many small island states face near-certain destruction.

Still, this can feel a bit detached from everyday reality: a theoretical future most of us won’t be around for, discussed in technocratic terms by academics and experts. A mere decade ago, concerns fell on deaf ears. (Now, Extinction Rebellion could not be more loud and clear.)

Back then the issues were too big, too frightening. The detail just too much for ordinary people – and many politicians – to grasp. Sure, the forecasts were clear enough. If we continue to pump greenhouse gases (GHG) into the atmosphere, humanity faces a series of disasters of ever-more-biblical proportions, from fire, floods and droughts to the ultimate rendering uninhabitable of large portions of the planet. We needed mitigation to address the causes of climate change (reduce emissions and remove them from the atmosphere) as well as adaptation to address the impacts of change.

The problem? It required money, resources and sacrifice: countries that had benefited from an unfettered GHG world would have to take less, while those yet to enjoy such affluence would have to accept they never would. The US would have to stop guzzling fossil fuels at a rate of 15.5 metric tons of CO2 per capita, while countries such as China (6.6) and India (1.6) would never have the chance.

But money and technology are needed to help countries adapt and mitigate. Where would this money come from? Logic – and justice – suggest the wealthier nations that caused the mess in the first place. Realpolitik took us elsewhere, to a place where the US became concerned with defending the new, carbon-reducing technology, and many of the richer nations argued that developing nations should foot the bill.

It does not take a genius to see how this was never going to work.

And all of this overlooks the fact that significant actors, including major fossil fuel producers, were lobbying hard against anything that might curtail their right to make money by continuing to pollute.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s William C Tucker put forward a more realistic call for action in 2012 with an article in Ecology Law Quarterly that questioned whether climate change denial was a crime.

Tucker started with an idea we’ve come to know well: “Climate change poses a grave threat to humankind”.

He showed that despite growing evidence of the damage being done by the emission of GHGs over two decades, the US government has failed to take effective measures to address climate change at home or in the international sphere. Moreover, he said “it is now well-documented that a shift in public opinion and failure of political will on climate change took place at the turn of the millennium, a change which can be largely attributed to a sophisticated, nationwide public relations campaign designed to conceal the dangers of burning fossil fuels from the American public by deceiving it as the true state of climate science”.

It is now well-documented that a shift in public opinion and failure of political will on climate change took place at the turn of the millennium, a change which can be largely attributed to a sophisticated, nationwide public relations campaign designed to conceal the dangers of burning fossil fuels from the American public by deceiving it as to the true state of climate science

Great stuff! The legal journey that follows is equally persuasive. Sure: the US constitution protects the promotion of honest views. But “the constitution does not protect dishonest or fraudulent speech, and without honesty there can be no meaningful public ‘debate’”.

He examines claims that the public debate is being skewed by massive, high-level, systemic spin-doctoring. He finds there is more than enough evidence to show active deception by several megacorps – and their friends in the political establishment – and goes on to look at the remedies available to different groups on the grounds that fossil fuel advocates have been committing fraud. Against individuals. Or, more serious, conspiring to defraud the US in its entirety.

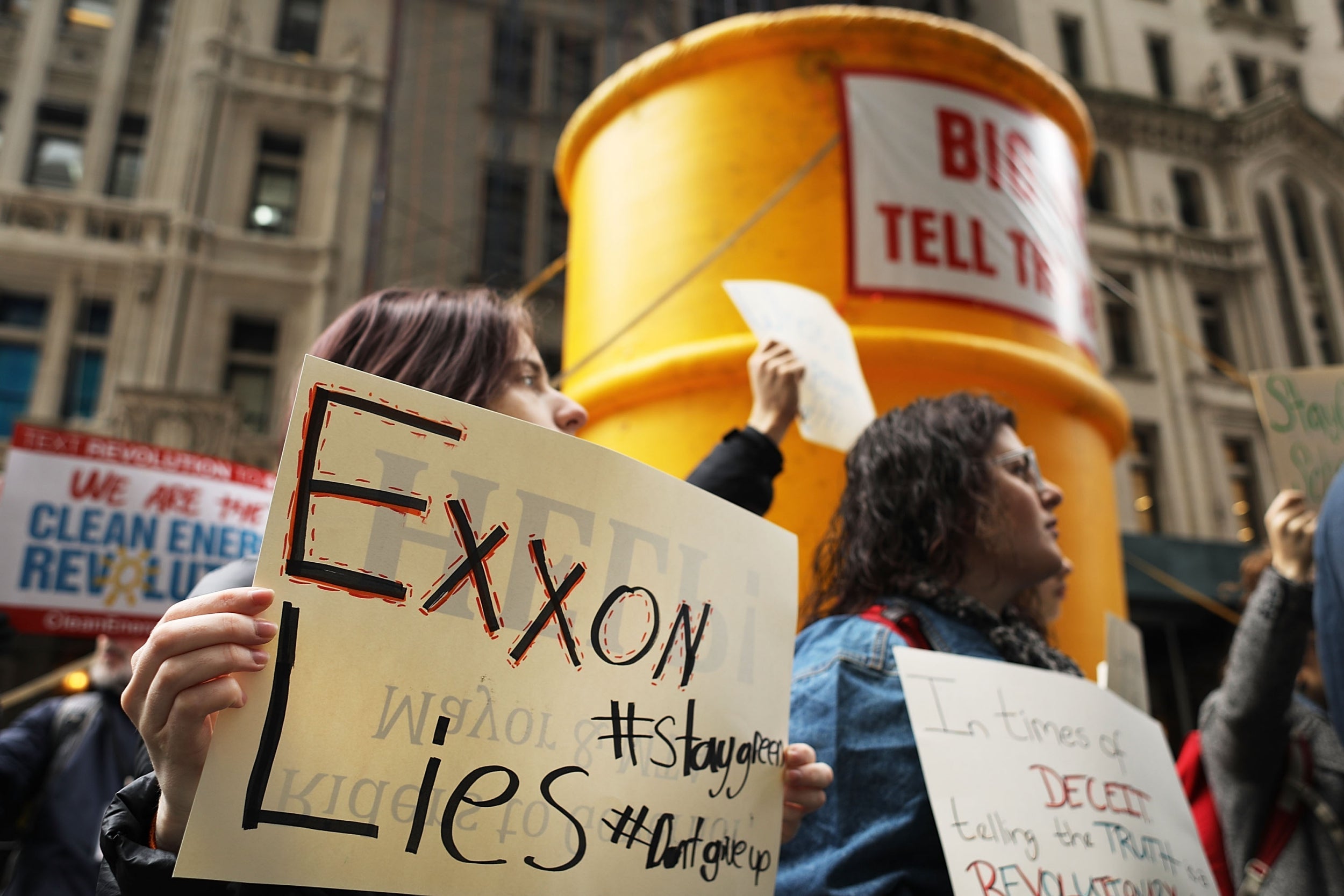

Since then, the legal debate has shifted up a notch, as increasingly creative alternatives are proposed to deal with climate change deniers. Interventions already underway range from a consortium of nine cities suing the fossil industry for climate damages to California fisherman taking on oil companies for destroying their livelihoods.

Elsewhere, state attorney generals are investigating whether ExxonMobil has misled its shareholders over the risks it faces from climate change or defrauded the public by spreading disinformation about climate change. Separately, Our Children’s Trust has begun an action – Juliana vs the US – arguing that government actions causing climate change have “violated the youngest generation’s constitutional rights to life, liberty and property, as well as failed to protect essential public trust resources”.

These actions, though welcome, according to Kate Aronoff, a fellow at the Type Media Centre, are just the beginning. The time has come to take proceedings to the next level and try fossil-fuel executives for crimes against humanity, she wrote in an article for Jacobin magazine earlier this year.

Aronoff is not the first to make such a call. In October 2018, Jeffrey Sachs, head of Columbia University’s Centre for Sustainable Development, suggested something similar, taking aim at politicians like Donald Trump and Marco Rubio.

Without a doubt, there is something in the air – and not just more CO2.

Perhaps the most significant change lies in the fact that we are no longer living in the technocratic bubble of 2010. From the slightly parochial menace of a dam bursting in the north of England to wildfires on the west coast of the US, the consequences are being felt daily.

Real damage is happening. Real costs are being incurred, with insurance bills for natural disasters running into the billions. And real people are dying.

Public tolerance for deniers such as Mike Talbott, the former head of Houston’s flood control district, is waning. Interviewed in 2016 after Houston had been hit by the second of two back-to-back “hundred-year floods”, incredulity followed his admission that he still had no plans to study climate change or its potential impacts on the county.

Is this just opinion, or something else? Negligence, perhaps, given that a consequence of Talbott’s wilful complacency is that the damage from Hurricane Harvey was more serious and, it is argued, the death toll higher.

The problem is: we can rarely tie specific damage to specific actions. Yes: the ravages wrought by drought, wildfire, flooding and hurricanes are going to get worse. A lot worse.

At a global level, several nations, mostly in the Pacific, could be overwhelmed. From the Maldives to Vanuatu, from Samoa to the Solomon Islands, the future is bleak. And not just because they will disappear beneath the waves: Kiribati, an official representative tells me, will simply become uninhabitable due to a lack of safe drinking water.

Whether it is massive flooding in countries such as the Netherlands and Bangladesh, or whole regions rendered uninhabitable due to intense heat, population displacement will be the result.

Or, to take away the technocratic language: millions of people who once lived sustainable lives in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, will be on the move – and many may, in time, consider it only right that nations such as ours, that caused the problem in the first place, put them up.

When it comes to delivering justice for the eventual victims of climate change, the first priority must be to help them survive – and that will cost us dear. But after that comes the questions, raised here, of whether legal retribution is appropriate and if so, to whom and how.

Historically, our record of dealing with political and corporate misdemeanours, even when they result in death and destruction on an industrial scale, is patchy.

In respect of Nazi war crimes, the overt and murderous nature of the “Final Solution” was exposed at Nuremberg – which also gave rise to a series of principles for determining what constitutes a war crime.

When it comes to deaths caused not just by smoking but also as a direct result of misinformation put out by cigarette companies, there seems little appetite for charging individuals. But the principle of tobacco companies paying out compensation that runs into billions is well established.

For now, the situation in respect of climate change seems to fall somewhere between the two: action is being demanded in cases of clear-cut negligence. But the broader charge of crimes against humanity – acts deliberately committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian or an identifiable part of a civilian population – is hard to sustain, not least because it is a much more nebulous area of the law.

One significant intervention in this area comes from Netherlands-based Stop Ecocide, a law-based group working to make ecocide a crime under international law.

In the end, though, the letter of the law may count for less than the mood of the people. If Britain – or any other nation or organisation – were to invade another country and evict the local population, that would be an act of war, whether it was treated as one by international courts or not.

We are in the process of doing just that to millions of people across the world and, once those people join up the dots, from Trump walking out of the Paris agreement to Bolsonaro pushing ahead with the destruction of the Amazon rainforest to oil companies continuing business as usual, the resulting anger will be a wonder to behold.

How culpable are they? Does it matter whether this is ignorance or greed? Just listen to Trump, who has single-handedly dismantled the Environmental Protection Agency, pontificate on how climate change is a difficult question and how we need experts to tell us about it and decide for yourself.

It feels inevitable that some of these people should be treated as criminals. The only remaining question is how far we hold others – the ones who only followed orders or, even, just voted for the wrong person – responsible. It would be wholly unfair to treat a Hillary-voting Democrat as somehow tarred with the Trump brush. Or would it? When it comes to crime, a long-held and respectable principle is that of deterrence.

Perhaps we do need to start being beastly to those being beastly to the planet. Americans, Brazilians… and maybe, before we get too smug, some Brits as well.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments