China’s one-party state cleans up air pollution in record time

For years the Chinese dismissed pollution as ‘fog’ but in 2014 they decided to tackle the problem with ‘an iron fist’ – and won. Phoebe Weston looks at a record-breaking clean-up campaign

In 2014 Beijing was deemed “almost uninhabitable” for humans. The country was seeing the worst stretches of pollution in its history, with levels hitting 45 times the recommended daily limit. Beijing was the 40th worst city in the world for a small lung-damaging particulate matter known as PM2.5.

For years authorities dismissed the poisonous blanket of pollution as “fog” but the problem grew too big to ignore and in one year the government went from denial to tackling the problem with “an iron fist”.

“We will resolutely declare war against pollution as we declared war against poverty,” Chinese premier Li Keqiang announced in 2014. It was a pivotal moment and marked the first time China had put the environment before economic growth. The policy has been so successful that five years down the line it is set to exit the list of the world’s 200 most polluted cities. Particulates were cut by more than 32 per cent and the promise of clean (or much cleaner) air was delivered.

The 70th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China was celebrated on 1 October. It was a little overcast but Beijing was free from Victorian levels of festering pollution. The “airpocalypse” was over.

Households were banned from burning coal for heat as part of a campaign to turn all coal heating to gas or electric. Officials even physically removed coal boilers from people’s homes

It’s not just China that’s struggling to give its citizens clean air to breathe. Globally, air pollution is the biggest public health problem, responsible for around 4.1 million deaths every year. But this is the story of how Beijing won the war against air pollution – and asks whether other countries could follow suit.

Between 1998 and 2013 China morphed from being an economic backwater into a vast global power and air pollution shot up by 75 per cent. During this rapid expansion, unregulated coal plants and heavy industries peppered the landscape – especially in the north – coughing out vast amounts of pollution.

In 2014 authorities did a U-turn and decided to clamp down on industrial pollution in its largest cities. Rather than creating market opportunities for green energy, the government's main tactic was to ban key sources of pollution. Coal-fired power plants were immediately prohibited in Beijing and the number of cars on roads were also restricted.

Households were banned from burning coal for heat as part of a campaign to turn all coal-heating to gas or electric. Officials even physically removed coal boilers from people’s homes and replaced them with electric or gas. In places where replacement heaters weren't ready, people were left to face winter without heating. Hospital wards froze and schools taught children outside to avoid freezing classrooms and try to glean some warmth from the winter sun.

In 2016 the government set up a Central Environment Protection Inspection to monitor the implementation of local environment laws. For Beijing, $120 billion was set aside to reduce air pollution. Despite immense human suffering, the policies worked. Now people in China can expect to live 2.4 years longer than they did in 2013 and the 20 million people living in Beijing could expect to live 3.3 years longer.

“These improvements in air quality in just four years are truly remarkable by any measure,” according to a report by Michael Greenstone and Patrick Schwarz from the Energy Policy institute at the University of Chicago. “By comparison, it took the United States a dozen years and the vicious 1981-82 recession to achieve similar reductions in air pollution after the enactment of the Clean Air Act in 1970.”

Our results show that the reduction in primary PM2.5 and secondary precursor emissions in the target regions comes at the cost of increasing emissions in neighbouring provinces

Beijing’s levels of PM2.5 have already dropped by almost 20 per cent this year compared with 2018.

“The most important lesson is that improving air quality is quite feasible on a short timescale, given sufficient commitment from both the government and the population,” said professor Oliver Wild from Lancaster University.

“Many of the pollution reduction measures have had additional benefits for the population: for example the continued rapid expansion of the metro system, and accelerating the switch to cleaner domestic fuels and to electric vehicles on the road,” he said.

However, despite these impressive declines, air pollution in China is still far too high. This year Beijing’s overall air quality is likely to be more than four times higher than the WHO guidelines of 10 micrograms per cubic metre. There is still room for improvement.

Not everyone has been a winner, according to research led by Beijing Normal University. In order to cut its own pollution, authorities moved industry out of the national capital region Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei (often referred to as Jing-Jin-Ji, or JJJ). This transferred the problem of PM2.5 emissions to less populous regions with lower environmental standards and inferior technologies.

“Unintended side effects of these policies to other environmental policy arenas and regions have largely been ignored,” researchers wrote in the paper published in Science Advances. “Our results show that the reduction in primary PM2.5 and secondary precursor emissions in the target regions comes at the cost of increasing emissions especially in neighbouring provinces.”

Prevailing winds also mean JJJ receives pollution from satellite towns such as Liaoning, Shandong, Henan and Shanxi but this is less than what was outsourced

“The main points of the study are that such emission outsourcing may impose pressure on their surrounding regions, thus the policy may not be able to solve the problem but rather move the problem somewhere else,” said Kuishuang Feng from the University of Maryland, who was an author on the paper.

“Stricter air pollution control policy will certainly reduce the emissions in the targeted regions or urban areas. However, consistent policy across the whole country would be able to prevent emission outsourcing and the air pollution control would be more effective.”

Despite cleaning up its own act, China is also dirtying the air of countries it trades with more than ever. “Over the last decade, China has become the biggest trade partner to continental Africa and to several countries in Latin America, homes to some of the world’s poorest people. At the same time, air pollution has surged in many of these countries, especially in Africa,” Jonas Gamso, assistant professor of International Trade and Global Studies at Arizona State University, wrote in a piece for The Conversation.

“Western governments have increasingly been pushing developing countries to protect their environments via trade agreements.

“In contrast, China does not push its partners to strengthen environmental protections. For this reason, trading intensively with China is especially likely to generate high levels of pollution in developing countries,” he wrote.

Pollution is to blame for one in five infant deaths in sub-Sahara Africa. Professor Gamso’s research showed that the environmental impact of trade with China depended on the nature of the African countries’ governments.

He said: “In countries with strong governance, such as Chile, Gambia and Tanzania, which scored near the top of my sample, trading with China had little impact on sulphur dioxide emissions and environmental public health. On the other hand, trading intensively with China worsened the air quality in countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia and Paraguay, which all ranked among the worst in governance.”

Professor Gamso said China should be doing more do push for stronger environmental laws abroad. As wages continue to grow, it is likely the government will face more lobbying domestically to improve environment trading standards.

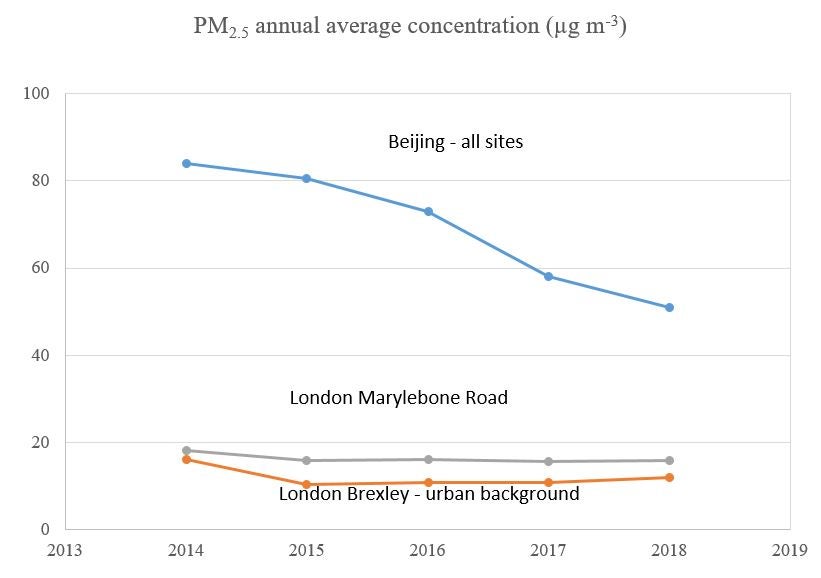

While Beijing’s PM2.5 levels have reduced by 35 per cent from 2015 to 2018, London’s urban background pollution has increased by 14 per cent. “It is important to note that the dominant sources of air pollution in Beijing can differ somewhat to those in London. Therefore, different policies need to be developed to tackle different pollution sources and air pollutants,” said Ben Silver, PhD student from the University of Leeds

“To put air pollution in the two cities into perspective: London’s annual mean PM2.5 concentration in 2018 was about one quarter of Beijing’s (12 micrograms per cubic metre in London and 50 micrograms per cubic metre in Beijing).”

While it’s relatively straightforward to get rid of the heaviest pollution, it’s difficult to make further reductions once the major sources have been removed. Although London is already looking to get to 10 micrograms Beijing probably won’t be thinking about this for another 20 years.

Despite power stations having gone, cities are still left with a number of sources of pollution from individual houses, offices and vehicles. The 10 microgram limit set by WHO is extremely challenging and scientists question whether any advanced megacities could guarantee its citizens such a low average.

“Even in a fully electric future, vehicles will still release particles from brake and tyre wear, and it is implausible to think we can eliminate friction. It’s also hard to imagine a city without cooking for example,” said Professor Alastair Lewis from the National Centre for Atmospheric Science.

“If enough people live together in a densely packed space, these almost irreducible sources of emissions mean 10 micrograms / m3 could well be breached no matter what.”

PM2.5 particulates can also travel in the wind from more than one hundred kilometres away. This means to tackle pollution, authorities need to look at local sources as well as sources from provinces around them. As discussed, regions surrounding Beijing are polluted but in London the main source of urban pollution is released locally from vehicles.

The air in rural parts of the UK is generally unpolluted as any remaining industries are tightly controlled and regulated. Favourable weather conditions also mean strong westerly winds dilute pollution in London.

Beijing, on the other hand, gets pollution blowing over from regions surrounding the North China Plain which tend to linger over Beijing meaning polluted air festers over the city for longer. “In China there are major sources of pollution right across the country, which means the cities and the rural background are both more or less equally polluted,” said Professor Lewis.

“Where the UK has urban hotspots of pollution, often at the roadside, China has entire weather systems that are polluted. A consequence is that working only at the city level is rather ineffective,” he said.

In the past decade China has made a number of impressive moves to improve its environmental credentials by cutting air pollution and saying no to Europe’s waste. It has reforested an area the size or Ireland in 2018 as part of its “Great Green Wall of China” programme and is also the biggest generator of renewable energy in the world.

If it wants to tackling greenhouse gases, the country will need action on a national – as opposed to regional – scale which will require significant restructuring of power generation. However, the country’s ability to tackle air pollution shows that should it decide to properly tackle environmental issues, its “iron fist” approach could prove very successful.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments