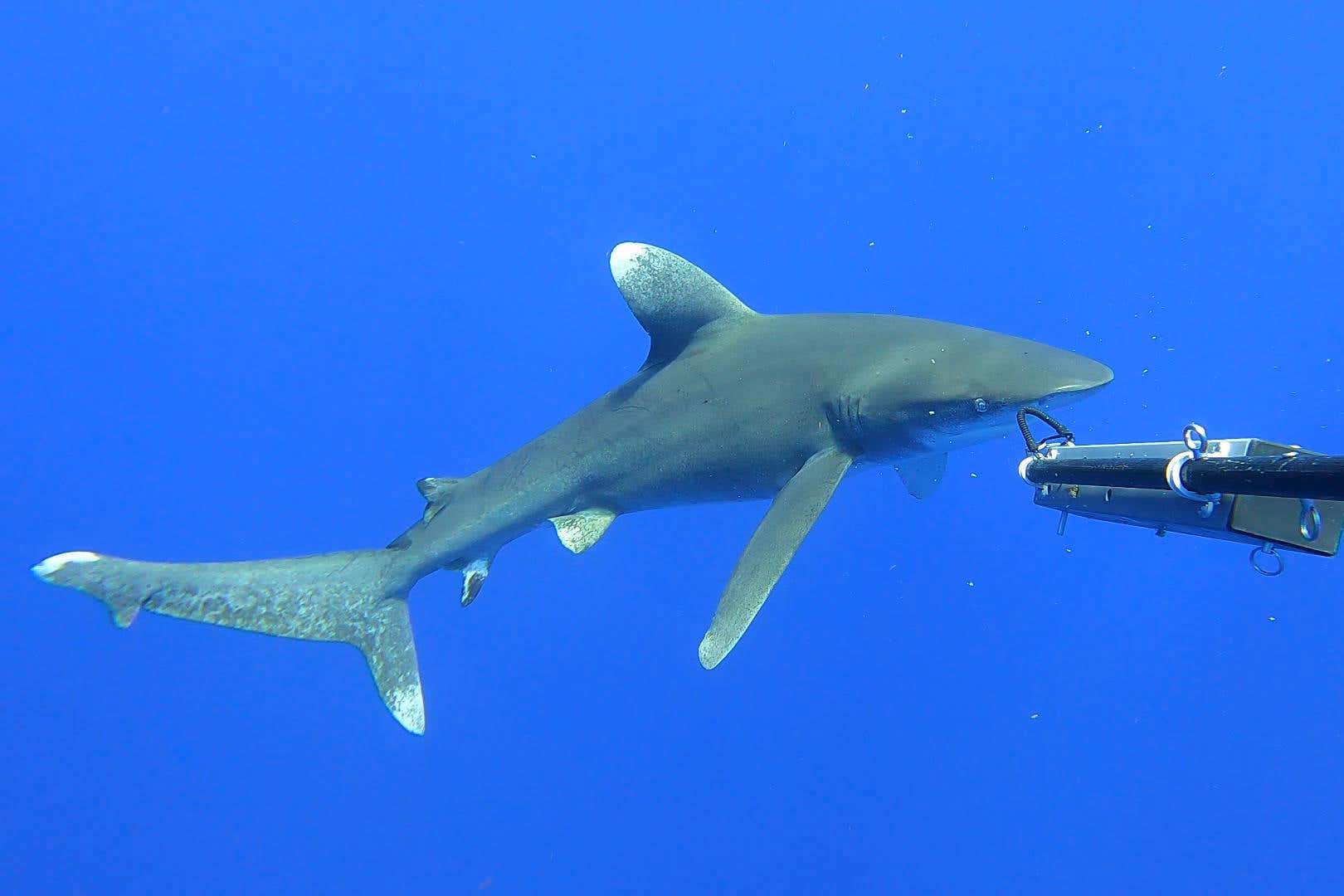

Rare on-screen glimpse of critically endangered oceanic whitetip shark

Scientists in the Cayman Islands are working to conserve the species and provide a haven for it in the Caribbean.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The oceanic whitetip is one of the world’s most endangered sharks that has declined by 98% throughout the world after being hunted for its fins or mistakenly caught in fishing nets.

Around the Cayman Islands, where the species is protected, scientists have made a rare, on-screen catch of the shark using a special camera that measures biological information without having to touch the animal.

Known as a baited remote underwater video (Bruv), the scientists hope to us this data to better inform conservation policies across the Caribbean.

They want their region to be a haven for the shark and other marine creatures that are facing extinction.

An apex predator, the oceanic whitetip used to be one of the most abundant species of shark swimming in the tropical oceans, but its preference for roaming near the surface means it is caught easily by fishing nets.

It is now rare in some regions, with the vast majority of the population having disappeared over the last 60 years.

We've got our waters protected, but now we can use this to help explain to other people - we need your help to protect these sharks

The International Union for Conservation of Nature classifies it as critically endangered, only one step away from extinction, and its slow reproductive cycle means it faces a long road to recovery.

Earlier this year near the coast of Grand Cayman, scientists working under the UK’s marine conservation Blue Belt Programme cast off their Bruv camera on the surface to see what creatures it would attract.

The shark, known for its inquisitive nature, was seen swimming around the camera and rubbing its head against the bait.

John Bothwell of the Cayman Islands Department of Environment, said the sharks are often seen on the surface but to capture one on camera was “amazing”.

He told the PA news agency: “You’ve got this beautiful video of what is really a charismatic megafauna for us.

“We’ve seen this with other video footage, in particular with other Bruvs, that we can then use to talk about these animals and the environment that they’re in and the threats they’re under.

“We’ve got our waters protected, but now we can use this to help explain to other people – we need your help to protect these sharks.”

But on a big picture, we're still generations removed from getting back to where they used to be. They will probably never get back to what they used to be, but we'll get them to something good

The Blue Belt Programme connects Overseas Territories from the Caribbean to the Antarctic to the Indian Ocean through scientific knowledge and resources with the aim of conserving unique ocean ecosystems.

Researchers want to provide policymakers in the Overseas Territories with a base of scientific knowledge that they can use to inform their conservation programmes and while showing why conservation is important.

Dr Paul Whomersley, lead scientist of the Blue Belt’s Global Ocean Wildlife Analysis Network project, called this “evidence-informed management”.

He said: “It’s always trying to use the science and the evidence to develop that policy and protection because we find that if you just go down that blanket route of saying no, it never works.

“But to actually be able to present why you think it’s important is really valuable.”

Blue Belt also allows researchers from different Overseas Territories and the UK to learn from each other how to manage their ecosystems or how to monitor illegal fishing.

Mr Bothwell said: “But of course, the first step is getting the protections in place locally and globally and then doing the science like this to figure out how much we have left and where are the hotspots for them.

“We’re so used to some of these species being under such reduced numbers, whether it’s sharks, marine turtles, whatever, and saying we’ve got a pretty good number there.

“But on a big picture, we’re still generations removed from getting back to where they used to be.

“They will probably never get back to what they used to be, but we’ll get them to something good.”