Inside the Canadian town wiped off the map by a heat wave: ‘I watched my pets burn alive’

‘I stayed up all night watching the town burn down. It was so scary,’ says one Lytton resident

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nine foot high flames were lapping at Pierre Quevillon’s Lytton home when he bundled his two dogs into his truck, ready to flee town.

He ran back inside to rescue his cat, only to return to his truck to find it already engulfed in flames.

With no choice but to abandon his burning vehicle, and the dogs inside, Quevillon fled town on foot, his cat in his arms.

“I ran towards the town and the fire was pretty much following me,” he says. “And in about 15 minutes, the whole town was gone.”

Quevillon is one of an estimated 1,000 residents of Lytton, British Columbia, who were forced to leave their homes behind and flee to neighbouring towns after wildfires razed much of the small Canadian town.

The BC Coroners Service has said it has received reports of two deaths related to the blaze, and many are missing.

The fire comes days after the temperature hit 121.1F (49.5C) in Lytton - the third day in a row that Canada’s all-time highest temperature was recorded.

Quevillon’s home was one of the first to go up in flames on Wednesday evening, after the town’s mayor issued an immediate evacuation order. A friend had called to warn him about the incoming blaze when he set about saving his pets, only to be forced to escape the town on foot with his cat.

“I couldn’t even see my truck anymore, the flames were nine feet high. So I ran,” he says.

“All the town was burning, the fire was coming towards me. Then, I got to the end of the town and the only thing left to burn was me.”

A passing driver picked Quevillon up and took him to a nearby hill, where the fire had already torn through. He spent the night “watching the town burn below me”. It was a hard sight for the Vancouver native, who had moved to the tiny community four years ago to renovate a friend’s house, and never left.

Nearby, 72-year-old Neil Dycke had managed to walk up the same hill on early Thursday morning, in order to escape the flames. He’d managed to gather a few belongings from his Lytton home before it became a blazing inferno. He’d mostly picked up photographs.

Dycke is a longstanding member of the community, having moved to nearby Spencer’s Bridge in 1970 to work as a fuel station attendant, before moving to Lytton. He said it had always been hot in the area, with summers around 40 degrees Celsius, but nothing like what had occurred this year. It was a similar notion with wildfires; they were common, as the area was so dry, but not like this.

Dycke loved the town because it was “quiet”, everyone knew each other, and he used to delight in speaking to tourists passing through to visit Alaska and the northern reaches of British Columbia.

Which is why watching it burn to the ground had been all the more devastating.

Dycke spent Wednesday night in Lytton, despite the mayor’s evacuation order, as he couldn’t find a way out. He slept at a friend’s house that was still intact.

Early Thursday, he made for the hills.

“There were electrical wires down everywhere. I was crawling under them and over them,” he says, still managing to smile at the memory.

Finding each other on the hill, Quevillon and Dycke picked up a friend’s truck and travelled together from town to town, trying to find shelter, before ending up in Chilliwack, 180 kilometres south of Lytton, at a temporary evacuation centre set up at the town’s secondary school.

Dycke was then allocated a hotel room to stay in for five days, and Quevillon had decided to stay with friends in a town nearby, awaiting the moment he could return home to survey the damage.

“I want to get back and rebuild the minute they say you can go back,” he says.

“We’re not sure still if everyone is okay there. I’m worried, because there are so many elderly people.”

Lytton evacuees were still trickling in to the evacuation centre on Friday morning, some with carloads of children and pets, desperate for a place to stay. Evacuees were then being offered hotel rooms, however, due to the number of wildfires in the area and the lack of accommodation, many towns were now full.

A Lytton resident, who asked not to be named, said Chilliwack was the fourth town he had tried to find accommodation in. He’d arrived in town at 4am on Friday morning and slept with his wife and children in his truck before heading to the evacuation centre.

“We’ve been bounced from town to town. I’m just trying to get my family situated.”

The road was now closed about five kilometres south of Lytton, as firefighters struggled to contain the out-of-control fires. Helicopters with monsoon buckets fly constantly up and down the narrow valley that leads into the town, collecting waters to spray the smouldering hills. Residents in towns in the region are ready and waiting to leave their homes at a moment’s notice, as wildfires nearby grow in size and threaten other communities. Fires near Kamloops, a larger town just north of Lytton, forced the evacuation of dozens of homes late on Friday.

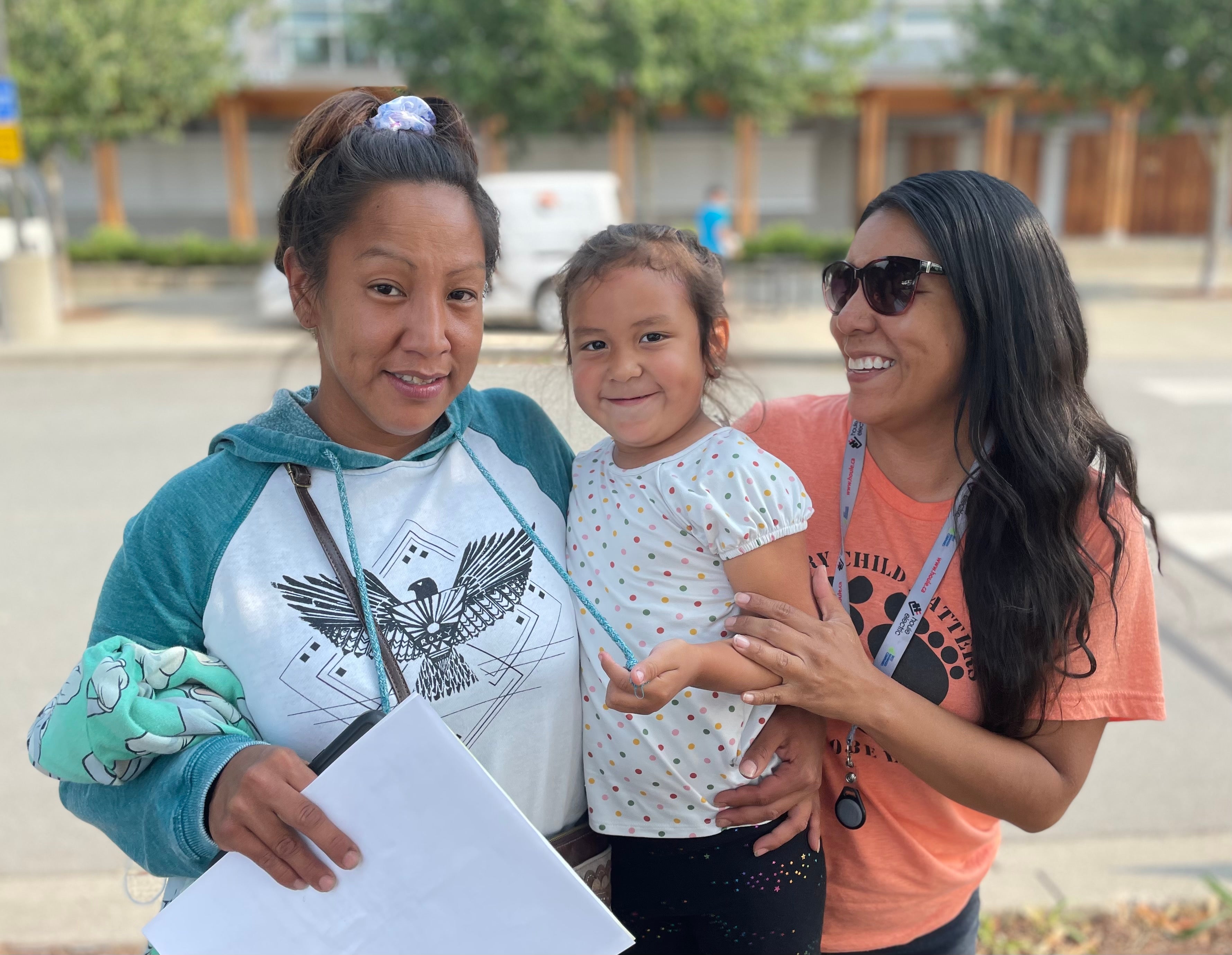

Karthryne Harry’s home was part of an estimated 10 per cent of Lytton that was saved from the fire.

Harry was inside her house with her four-year-old daughter Brooklynn “blasting the air conditioning and TV” when the sirens sounded to warn residents of the fire.

“We didn’t hear the sirens so we didn’t know the town was on fire. We went outside and there was all this black smoke coming from all the chemicals from the hospital burning - the propane tanks were exploding.”

Harry immediately set about furiously watering the lawn outside her house, as she battled to save the property. Luckily, the wind shifted and her home was spared, allowing the mother and daughter to remain in Lytton on Wednesday night as Harry didn’t have a car to leave town. There was no power, wi-fi or cellphone service.

“I stayed up all night that night watching the town burn down. It was so scary,” she says.

The next day, Harry’s sister Rainbow Acoby drove in from the nearby town of Merritt to help her sister. Thinking the fires had died down, the siblings settled in for another night, aiming to leave the next day.

“We were just lying down to go to bed and we heard that we’d been evacuated and the fire had jumped across the river. We freaked out and got in the car.”

The family arrived in Chilliwack at 5.30am on Friday morning, where they joined about 10 other displaced people from Lytton at Shxwha:y longhouse, a community centre run by a local First Nations family. The longhouse opened to provide food, clothing and mattresses to those fleeing the wildfires.

Volunteers there had gathered truckloads of donations to send north to fire evacuees and firefighters. Tables full of clothes, toiletries, food, Tim Hortons takeaway containers and clothes were piled high on tables in the front room.

On Friday evening, families from Chilliwack and fire evacuees alike gathered at the longhouse for a night of dance and song to offer support for fire evacuees.

Ron Prest, who runs the longhouse with his family, said the night was intended to “pick people’s spirits up” and was for “anyone who needs these prayers”. The longhouse shook with loud chanting and dancing, as the audience warded off the stifling heat with handheld fans, before tables laden with food were carried out to feed the congregation.

Prest said he expected more families fleeing the fires to turn up on Friday night, as other wildfires forced Lytton evacuees, and new evacuees, further afield.

“We’re just here for anybody who needs it. We’ve got beds and we’ve got food. We just want to look after the community.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments