Can birdwatching make us more passionate about the environment?

Social media didn’t just turn Matthew Stadlen into a photographer. It turned him into a twitcher too. Now he’s on a mission to turn our eyes to the skies, not just to raise awareness for our feathered friends, but to inspire an environmental movement

If you’re not someone who picks a fight with science, you’ll agree that our world is in trouble and we’re running out of time. How we force ourselves to change, whether it is driven from the top down by governments or from the bottom up by citizens – or both – is the defining question of our age. However we get there, though, it can surely only be a good thing to take a greater interest in the natural beauty all around us. If we pay attention to the wildlife on our doorstep, we are more likely to want to preserve the ecosystems that support not just the animals and birds with which we share our world, but also ourselves.

Birdwatching and photography can open your eyes to the everyday beauty that may be passing you by, whether you live in deepest countryside or innermost city. And, in turn, the inalienable duty we have to protect our environment, locally and globally.

We tend to overlook many of the treasures to which we have surprisingly easy access in our busy daily schedules. As Martin Harper, the global conservation director of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), puts it in his foreword to my new book, How to See Birds: “There are some things we take for granted: the passing of the seasons, the rising and the setting of the sun and even the wildlife that we often ignore as we carry on with our hectic lives.” But, he goes on: “If we only took time to stop for a few moments and look up, we would be reminded of the majesty of the natural world, the beauty of bird song and the artistry of flight.”

So, when you see a bird, do you really see it? Even if you can identify a common magpie, do you take the time to notice its glossy blacks, blues and greens illuminated in the shifting light? Have you ever stopped to marvel at the apparently dour starling as the sun transforms its colours into a rainbow iridescence? If we look, if we really look, there is so much to captivate us. And many of us are looking. There are in Britain more than a million members of the RSPB. And, thanks to the likes of Instagram, there is also a growing number of bird photographers opening the eyes of others to unimagined delights.

Social media has turned many of us into photographers and it’s also made an occasional twitcher of me. I sometimes drive implausible distances just to see and photograph a species for the first time – and I might not have bothered were it not for the dopamine hit posting your work online can bring. Along the way, I have come to admire the efforts we are already making in conservation around the country. But I’ve also come to realise that there is so much more to do.

The iconic cuckoo features strongly in my book. Its relationship with the English summer is both familiar and reassuring. In fact, one particular cuckoo makes its way over from Africa each spring to the same patch of ground in Surrey, where keen photographers feed it worms in a bid to catch a close-up of the typically shy species. This cuckoo has been nicknamed Colin and boasts legendary status. But Colin serves as a reminder of the challenges facing our birdlife. Like many of our migratory birds, the cuckoo has been struggling, its population having declined by 65 per cent since the mid-1980s.

The scale of our loss is enormous. In the words, again, of Harper: “There are 44 million fewer birds today than there were when England won the football World Cup in 1966 – with the majority of species in decline. We have not treated the other species with whom we share this planet with the respect that they deserve. We have destroyed or polluted their homes, persecuted them and made it harder for them to rear their young. To live genuinely in harmony with nature, our own species needs to change.”

My own birdwatching journey began when my uncle took me, aged eight, on a trip to the edges of the Highlands in search of golden eagles and ospreys. Birds of prey immediately impressed me, and it’s not hard to see why. The peregrine falcon can swoop down on its airborne target at 200 miles per hour. The jurassic-looking white-tailed eagle, which I have photographed off the coast of Mull, boasts a wingspan of comfortably over two metres. Today, though, I am almost as enthralled by the subtle beauty of the wheatear as I am by the majesty of the red kite in all its shimmering reds and whites.

I sometimes drive implausible distances just to see and photograph a species for the first time – and I might not have bothered were it not for the dopamine hit posting your work online can bring

Talking of the red kite, its thriving numbers represent one of this country’s conservation success stories. Brought to the very verge of extinction in the 1980s and confined to a tiny pocket of mid-Wales, this handsome scavenger is now a reliable sight on the London to Oxford road. Between 1989 and 1994, the birds were reintroduced from Sweden, Spain and even one from Wales to areas as diverse as the Chilterns and northern Scotland. The project was a triumph and kites soon began breeding both north and south of Hadrian’s Wall.

There are teams of bird-lovers across the country who commit themselves to the preservation of our landscapes for the benefit of our birds. Indeed, the same uncle who inspired my early interest in birdwatching used to protect peregrine falcons’ nests from poachers in Scotland.

That I was able to see two common cranes and their yolk-yellow young at Slimbridge in Gloucestershire is also thanks to the efforts of British conservationists. These incredible birds, with their metallic red crowns and long legs, were helped to breed as part of the Great Crane Project, an initiative which returned the famous creatures to the southwest of England between 2010 and 2014. Eggs were collected in Germany before hatching here and 93 common cranes were hand-reared for release onto the Somerset Levels and Moors. The British Crane population has doubled as a consequence.

Travel, however, is not a prerequisite of a successful day’s birding. You don’t have to be in remote corners of the globe to enjoy birds, nor even in the British countryside. Wherever you live in the UK, you are likely to be within eyesight, or at least earshot, of a surprisingly extensive range of species. I’ve counted more than 20 in my parents’ garden alone. Not bad for central London. From the comforting grey heron, as it lopes across the rooftops, to the miniature long-tailed tits flitting through the bushes, from the green woodpecker with its ungainly call to the graceful mute swans flying in formation, birds are at ease in our towns and cities. There really is beauty all around us, if only we lift up our eyes to see.

Not to forget pricking our ears to hear. Bird song is often an indispensable guide to identification, and it can be the sweetest of music, too. Listen out for the blackcap singing in the spring; notice the common blackbird, with its bright yellow bill, warbling from the tip of a rose bush in summer. What better soundtracks to the day?

Birds aren’t only aesthetically alluring, either – they have extraordinary stories to tell, too. Willow warblers are just over 10cm long, but each spring these tiny green, yellow and white leaf warblers fly 5,000 miles to reach us from Africa, having crossed desert, sea and mountain. And they do it without jet fuel!

Maybe it won’t surprise you that many birds can navigate vast distances using rivers, roads and coastlines as signposts. More amazing, though, is that juvenile cuckoos are able to migrate successfully despite never having met their parents. How they are programmed to find their way is said to be one of the great unsolved mysteries of nature.

It hasn’t always been “cool” to be able to tell the difference between a blue tit and a great tit, but a 2004 study found that nearly 3 million people aged over 15 go birdwatching in the UK regularly or occasionally. A decade and a half later and we are now at a tipping point for birding. As bird photography booms, more and more of us seem to be waking up to the lavish variety of avian life in our midst. Where once a close friend would have raised an amused eyebrow had I pointed out a pair of bullfinches making their way from branch to branch, these days she has a beady eye of her own for distant raptors.

3 million

people aged 15 and over go birdwatching in the UK regularly or occasionally

It always struck me as peculiar that taking pleasure in the natural world around us, whether we live in urban or rural habitats, should be considered quirky or, worse, the object of ridicule. Yes, there are the life lists, the species counts, the hint of competition, too; but at its core, birdwatching is about immersing yourself in nature.

I can remember the first red-footed falcon I spotted sweeping to and fro across an Albanian mountainside. So, too, my first barn owl as it jumped from tree to tree in search of food in the snowdrifts of a Welsh country lane. But there are other, more profound needs, that watching birds can fulfil. Meditation is one. When photographing birds, or just birdwatching, you can lose yourself in the experience. Drawn into the avian world around you, you become as close to nature as you will ever be. Distracting thoughts fade away…

Improving as a photographer, meanwhile, is as much about being disappointed in what hasn’t worked as it is about enjoying what has. For most, it really is a case of trial and error. You pick up just as much from that almost-brilliant image as you do from the rare times when you take a shot of which you are proud. The essential thing is to be interested in the bird. The more you understand about your subject, the greater the chance you’ll produce a strong photograph. And it works the other way round, too: the better your photography, the more you’re likely to appreciate and understand the bird.

Today, I don’t even own a pair of binoculars and travel instead with my Nikon. It has a 500mm zoom lens that can reveal breathtaking detail even at challenging distances. And if I’m unable to identify a bird with the naked eye, I can compare my photographs with the images I google on my phone.

Here’s a memorable example: for decades, I’d wanted to see a merlin. It is Britain’s smallest bird of prey and something about the contrast between its neat features and deadly will intrigued me. While I was out looking for hen harriers in the Cambridgeshire Fens, a flock of birds sprung into the air in a terrible frenzy, startled as they had been from the bushes. Almost immediately, two peeled away from the crowd and darted to the left. Within a moment I realised that this was a chase and that, in fact, one of the pair was a miniature raptor, not much larger in size than its prey.

Kestrels have been known to hunt clustered birds on the wing but this attacker seemed too small and the behaviour more characteristic of a merlin. To my huge frustration, though, I wasn’t quick enough with my camera so I couldn’t be certain. Only months later, when I managed to capture a darting grey shape flying close to the ground across wetlands in Oxfordshire at the RSPB Otmoor reserve was I sure that I had, finally, seen a merlin. The image was blurred, but the bird’s identity wasn’t in doubt.

There’s a social side to bird photography, too. I once was able to match a face to an Instagram account I’d seen when I got chatting to a hospital doctor at the same reserve. Another time, when one of the listeners to my radio show started following me, I discovered her brilliant bird photos and she gave me directions to find the little owl she had snapped in a London park.

There are those, as you probably know, who take birdwatching several steps further. Twitchers make their way specifically to areas of the country where a rare species has been spotted. They can travel thousands of miles a year in pursuit of their passion. I once discovered via a colleague’s Twitter account that two bearded tits had turned up in the reed beds by the Diana Memorial Fountain in Hyde Park. The male is one of our most handsome birds, with a russet cloak, azure head and its eponymous black beard. I went with my mother to investigate and found what appeared to be two females by the water.

More recently, I have driven far further in pursuit of rare visitors. Perhaps most thrillingly, after a long trek to the Essex coast, I watched a rough-legged buzzard catch the evening sun as it hunted above a golf course. But I am an amateur in comparison to Lee Evans, a famous twitcher I once spotted on a Norfolk beach while I was among a group of birdwatchers attempting to distinguish between an isabelline and desert wheatear. Lee reportedly travelled 70,000 miles to see 352 of the 390 species that were recorded in the UK in 1992.

However you choose to enjoy birds, if you buy yourself a pair of binoculars or a half-decent camera, you won’t be treading a lonely path. But it is important to be mindful that whether we are out to take photographs or just to look, the welfare of the birds we’re searching for should always take priority. Some species, in fact, are protected by specific legislation. The kingfisher, for example, is a Schedule 1 bird, which means it is afforded special protections under the law. It is an offence to intentionally or recklessly disturb Schedule 1 species at, on or near an active nest.

There are, of course, birds that we never see on British shores, and my ornithology has accompanied me around the world. I’ve taken photographs in Iceland, Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa. Many years ago, during a stay near the Point Reyes Peninsula in Marin County, just across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco, I added around 60 species to my life list. And I’ll always remember the morning in my teens when I was camping in the hills near Nelspruit in northeastern South Africa. While making use of the outdoor loo, shielded only by bushes, a spectacularly coloured bird with a long tail fluttered above me. It was a paradise flycatcher and the contrast between the grimness of my surroundings and the magnificence of my companion was surreal.

More recently, I have watched honey buzzards circle high above Italian fields, crept close to hummingbirds hovering in Santa Barbara and photographed orange-breasted sunbirds in Cape Town’s Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens. In all, I’ve seen something like 900 species, although I’ve only been able to identify just over 600 of them.

Nothing gives you a greater thrill than seeing a new species for the first time. My book is not a guide or a gospel, but a call to inspire and motivate you to take an interest in birds and help to protect our vulnerable wildlife for future generations. Through a more developed sense of what our planet has to offer, I hope we will all do much more to protect it.

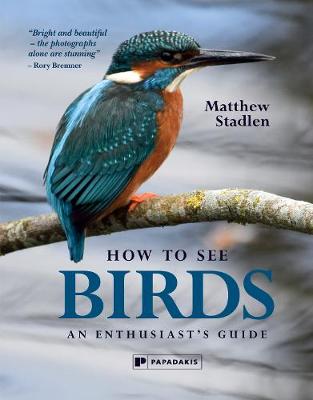

‘How to See Birds’ by Matthew Stadlen is published by Papadakis (£20)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments