Battle for Jefferies' land: How a 19th-century naturalist became a cause célèbre in Wiltshire

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They didn't do bestseller lists in Richard Jefferies' day, but even if they had, it's hard to imagine him submitting to the publicity interviews and book signings faced by the modern commercial author.

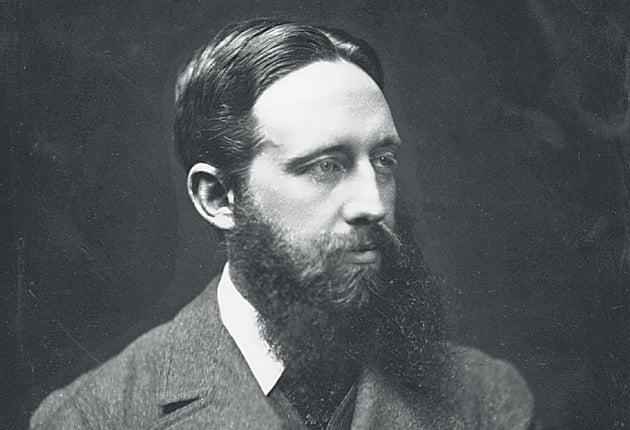

In fact, Jefferies, a reclusive, unworldly man – "long, languid and loitering", according to his biographer, Edward Thomas – was a journalist and nature writer of remarkable purity and intensity of vision. Even before his death, from tuberculosis aged 38 in 1887, cult rather than mainstream status was always his most likely destiny.

However, after a period when they seemed to fade from view, Jefferies' books are being read once more. They carry heightened value at a time when a backsliding David Cameron has gone from vowing to make his government "the greenest ever" to preparing a loosening of the planning rules that could unleash a bonfire of the countryside.

In his introduction to a new edition of Wild Life in a Southern County, first published in 1879, Richard Mabey refers to Jefferies' "electric attentiveness, a noticing that is hard to aspire to", and says that he was "sending a message in a bottle from a fast-disappearing country". However, that message seems not to have registered with those entrusted with guarding the integrity of the immediate landscape which charged his creative output.

Jefferies grew up and, until he married aged 25, lived on a tiny farm at Coate, near Swindon. Here his father kept a small dairy herd, but while Jefferies showed little interest in helping out on the farm, he inherited his father's love of nature, and spent his days exploring the surrounding meadows and hills, studying flora and fauna and seeking out archaeological sites, while honing the distinctive earth philosophy that elevated his work beyond mere observation.

Today Coate farmhouse, its outbuildings and orchard, all so vividly described in his novel Amaryllis at the Fair, survive as the Richard Jefferies Museum. Beyond the ha-ha, dug by Jefferies Snr to prevent the cattle straying into the orchard, is the ancient hedgerow recognised by Jefferies in Wild Life in a Southern County as "the highway of the birds". Over the ridge beyond is the reservoir of Coate Water, the scene for the mock battles of his children's novel Bevis. On the skyline is Liddington Hill, crowned by an iron-age hillfort, one of the numerous tumuli of the North Wiltshire hills which the writer memorably wrote of as being "alive with the dead". It was while lying on the slopes of Liddington Hill that Jefferies experienced the first of what he termed the "soul experiences" leading to his extraordinary autobiography, The Story of My Heart.

Developers have been eyeing the area around Coate Water for years, however, encouraged by a general refusal of the council's planning department to recognise Jefferies as "a major writer". A current proposal to build 900 homes and a business park was recently rejected by councillors – stunned by the strength of an opposition campaign which has seen protest letters written in the Times Literary Supplement and a petition signed by over 52,000 people. While that rejection was the first time, says Jean Saunders, secretary of the Richard Jefferies Society, that there had been any recognition of the cultural landscape value of Coate, the developers have appealed and a public inquiry is to be held.

That it should have got this far is testimony enough to Swindon Council's failure to appreciate its local heritage, but in refusing to accept Jefferies as a major writer, they turned the issue into a matter of national concern.

The list of artistic figures inspired by Jefferies is long and distinguished. Among literary names alone they have included Thomas, Henry Williamson (a past president of the Jefferies Society) and John Fowles. Andrew Motion has described Jefferies as "a prose-poet of the English landscape and a pioneer environmentalist". Like Thomas Hardy, Jefferies was alarmed by the pace of social change in late 19th-century England. Yet he was not some parochial figure, tiptoeing "feather-footed through the plashy fen", like William Boot in Evelyn Waugh's Scoop.

Nature Near London (1883) was written to alert Londoners to the countryside which lay on their doorstep, but Jefferies was not anti-progress, admitting he dreamt in London quite as much as in woodland: "I like the solitude of the hills and the hum of the most crowded city; I dislike little towns and villages." What he found intolerable was the suburban conformity and neatness – "artful niceness" – that was spreading like a suffocating blanket from the city's outskirts.

Edward Thomas thought that, whereas the writing of Gilbert White, the "godfather" of nature writers, was weighed down by the dead-weight of "matter of fact", Jefferies was the first nature writer whose essays led us to his own personality.

However, the major relevance of Jefferies today is surely that he found nature everywhere, pushing up through the cracks on the busiest pavement. In The Life of the Fields (1884) he describes watching the pigeons in the forecourt of the British Museum, for whom Robert Smirke's great neo-Grecian portico was no entrance to a temple of learning but "merely a rock pierced with convenient openings".

Officialdom, if it had its way, would like to parcel up the best parts of the countryside into "approved" areas, facilitating a developers' profitable free-for-all over the remainder, having thought it sold us the dummy that anything undesignated must therefore be without value.

But Jefferies, reared on the homely terrain at Coate, urged us to seek uncommon species in common places. A commonplace flower held as much delight for him as a rare one. No wonder the planners of Swindon would have us believe he wasn't a major writer. He was their spiritual enemy, and his prose still hounds them from his grave, 120 years after his death.

For information on Richard Jefferies and the campaign to save "Jefferies land", visit www.jefferiesland.blogspot.com

The other late, great nature writers

REV GILBERT WHITE (1720-93)

His The Natural History of Selborne, never out of print since first publication in 1788, is a work of science that is also a literary classic. By basing it on first-hand observation, not generalised philosophising, as was prevalent at the time, White pioneered the genre of natural history writing.

He was a Hampshire vicar who spent most of his life in the tiny village of Selborne. His home, the Wakes (now a museum), together with the Great Mead, Church Meadow and the beech hanger where he carried out many studies, are still evocative of his time.

JOHN CLARE (1793-1864)

The so-called peasant poet was the self-taught son of an illiterate labourer. After a brief period of fame, disillusionment at the failure of his poems to sell precipitated a mental collapse, and he had two spells in an asylum. Like Jefferies, another outsider hero, he detested the landowners he felt were exploiting the countryside for their own profit. The cottage in which he lived for much of his life, at Helpston, near Peterborough, recently opened as a heritage centre.

WH HUDSON (1841-1922)

The most exotic of "English" nature writers, Hudson grew up in Argentina, roaming the pampas plains and keeping the company of gaucho herdsmen. A keen ornithologist, he discovered a new species of tyrant bird in a Patagonian river valley, subsequently named Knipolegus Hudsoni.

Arriving in England, aged 32, in 1874, he struggled for years to get work published. However, Nature in Downland (1900) – vividly describing the South Downs – arguably wears better than the widely acclaimed A Shepherd's Life (1910) in which his affinity with the solitary shepherds of the Wiltshire Downs – soul brothers of the Argentine herdsmen – is clear.

HILAIRE BELLOC (1870-1953)

A belligerent Roman Catholic apologist and satirist of the political classes, his country writing, showing a gentler side, has been almost overlooked.

French-born, from the age of eight Belloc's childhood was spent playing in the chalky lanes beneath the Sussex Downs at Slindon, whose swaying beechwoods he'd describe "noisy in the loud October". He returned to live there in adulthood, then at nearby Shipley, with its windmill at the bottom of the garden. More celebrant of the outdoors than naturalist, his poems – "lift up your hearts in Gumber, laugh the Weald" – celebrate the West Sussex Downs with the heady exultation of the keen walker he was.

EDWARD THOMAS (1878-1917)

Like Richard Jefferies, Edward Thomas was alert to nature even while passing through the busy throng of London's West End. A walker and cyclist, he wrote books such as The South Country (1906) and In Pursuit of Spring (1914) before turning to poetry on the eve of the First World War. His biography of Jefferies is still probably the best, not least because it was written at a time when many of those who remembered him were still alive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments