Climate change: The devastation of Australia’s ocean

As fires rage, the tragedy playing out underwater is much worse, but invisible to most. Darryl Fears looks at the devastation being caused in the climate crisis

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Even before the ocean caught a fever and reached temperatures no one had ever seen, Australia’s ancient giant kelp was cooked.

Rodney Dillon noticed it the day he squeezed into a wet suit several years ago and dove into Trumpeter Bay to catch his favourite food, a big sea snail called abalone. As he swam amid the towering kelp forest, he saw that “it had gone slimy”. He scrambled out of the water and called a scientist at the University of Tasmania in nearby Hobart. “I said, ‘Mate, all our kelp’s dying, and you need to come down here and have a look.’

“But no one could do anything about it.”

Climate change had arrived at this island near the bottom of the world, and the giant kelp that flourished in its cold waters was among the first things to go.

Over recent decades, the rate of ocean warming off Tasmania, Australia’s southernmost state and a gateway to the South Pole, has climbed to nearly four times the global average, oceanographers say.

More than 95 per cent of the giant kelp – a living high-rise of 30ft stalks that served as a habitat for some of the rarest marine creatures in the world – died.

Giant kelp had stretched the length of Tasmania’s rocky east coast throughout recorded history. Now it clings to a tiny patch near Southport, the island’s southern tip, where the water is colder.

“This is a hot spot,” said Neil Holbrook, a professor who researches ocean warming at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania. “And it’s one of the big ones.”

Disastrous impacts from climate change aren’t a problem lurking in the distant future: they are here now

Climate scientists say it’s essential to hold global temperatures to 1.5C above preindustrial times to avoid irreversible damage from warming.

The Tasman Sea is already well above that threshold.

The Washington Post’s examination of accelerated warming in the waters off Tasmania marks this year’s final instalment of a global series, which identified hot spots around the world. The investigation has shown that disastrous impacts from climate change aren’t a problem lurking in the distant future: they are here now.

Nearly a tenth of the planet has already warmed 2C since the late 19th century, and the abrupt rise in temperature related to human activity has transformed parts of the Earth in radical ways.

In the United States, New Jersey is among the fastest-warming states, and its average winter has grown so warm that lakes no longer freeze as they once did. Canadian islands are crumbling into the sea because a blanket of sea ice no longer protects them from crashing waves. Fisheries from Japan to Angola to Uruguay are collapsing as their waters warm. Arctic tundra is melting away in Siberia and Alaska, exposing the remains of woolly mammoths buried for thousands of years and flooding the gravesites of indigenous people who have lived in an icy world for centuries.

Australia is a poster child for climate change. Wildfires are currently raging on the outskirts of its most iconic city and drought is choking a significant portion of the country.

Nearly 100 fires are burning in New South Wales, nearly half of them out of control. Residents of the state, where Sydney sits, wear breathing masks to tolerate the heavy smoke, which has drifted more than 500 miles south to the outskirts of Melbourne.

Dillon and other descendants of Tasmania’s first people are losing a connection to the ocean that has defined their culture for millennia

This is happening even though average atmospheric temperatures in Australia have yet to increase by 2C.

The ocean is another story.

A stretch of the Tasman Sea right along Tasmania’s eastern coast has already warmed by just a fraction below 2C, according to ocean temperature data from the Hadley Centre, a UK government research agency on climate change.

As the marine heat rises and the kelp simmers into goo, Dillon and other descendants of Tasmania’s first people are losing a connection to the ocean that has defined their culture for millennia.

Aboriginals walked to present-day Tasmania 40,000 years ago during the Stone Age, long before rising sea levels turned the former peninsula into an island.

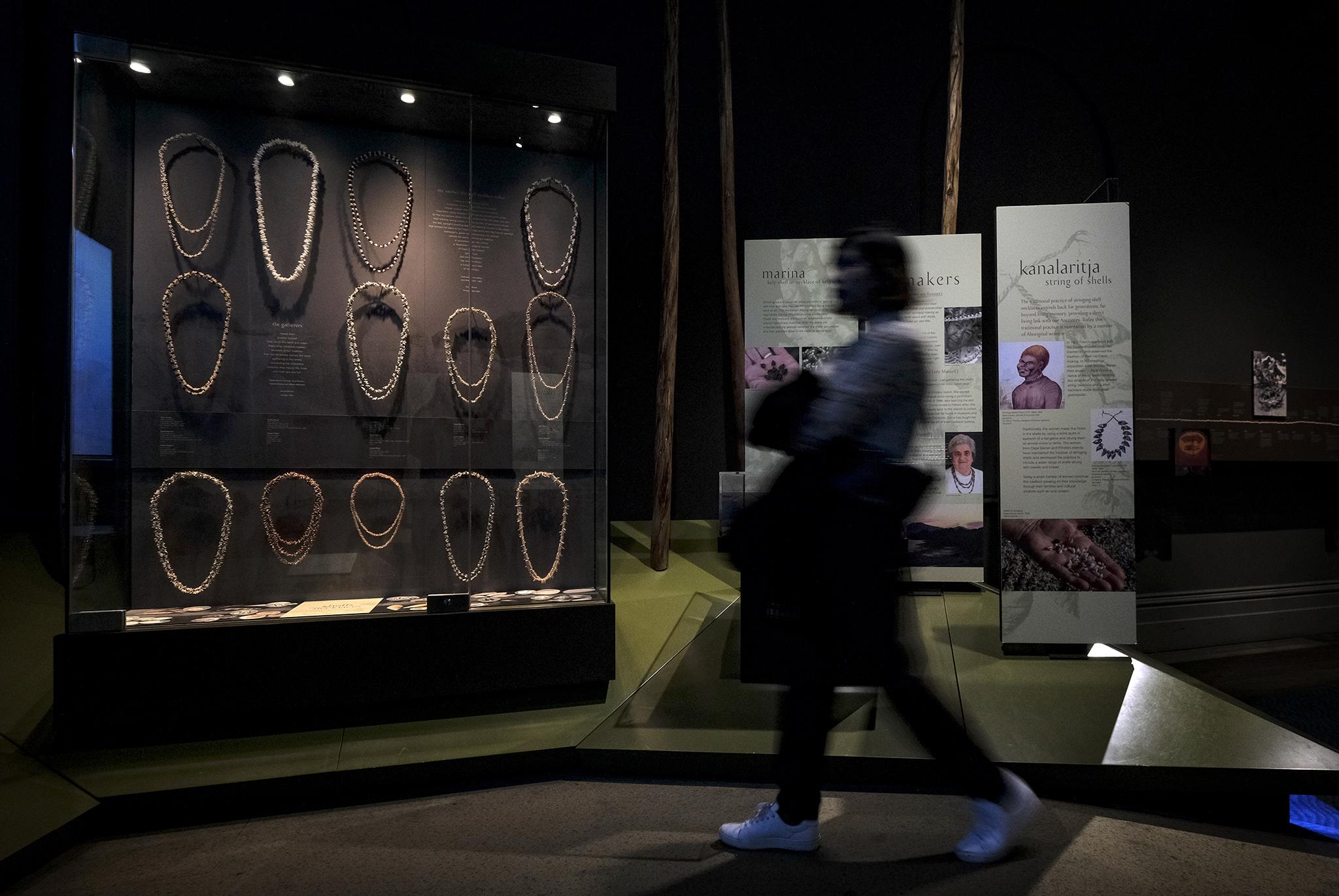

Cut off from Aboriginals on the mainland, about a dozen nomadic tribes were the first humans to live so close to the end of the Earth, fishing amid the giant kelp for abalone, hunting kangaroo and mutton birds, turning bull kelp into tools, and fashioning pearlescent snail shells into jewellery for hundreds of generations.

But that was before British colonisers took their land and deployed an apartheid-like system to wipe them out.

Now, as descendants try to finally get full recognition as the first people of Tasmania, climate change is threatening to remove the marine life that makes so much of their culture special.

Two of the most severe marine heatwaves ever recorded struck back to back in recent years.

In the first, starting in 2015, ocean temperatures peaked at nearly 3C above normal in the waters between Tasmania and New Zealand. A blob of heat that reached 2C was more than seven times the size of Tasmania, an island the size of Ireland.

The region’s past heatwaves normally lasted as long as two months. The 2015-16 heatwave persisted for eight months. Alistair Hobday, who studied the event, compared it to the deadly 2003 European heatwave that led to the deaths of thousands of people.

“Except in this case, it’s the animals that are suffering,” said Hobday, a senior research scientist at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, an Australian government agency.

The warming waters off Tasmania are not just killing the giant kelp, but transforming life for marine animals

South of the equator, Australia’s summer stretches from December to February – and soaring temperatures turned the mainland deadly this year. An estimated 23,000 giant fruit bats – about a third of the Australian population – dropped dead from heat stress in Queensland and New South Wales in April.

The bats, called flying foxes, cannot survive temperatures above 42C. Another 10,000 black flying foxes, a different species, also died. Bodies plopped into meadows, backyard gardens and swimming pools.

A month later, more than 100 ringtail possums died in Victoria when temperatures topped 35C for four consecutive days.

The warming waters off Tasmania are not just killing the giant kelp, but transforming life for marine animals.

Warm-water species are swimming south to places where they could not have survived a few years ago. Kingfish, sea urchins, zooplankton and even microbes from the warmer north near the mainland now occupy waters closer to the South Pole.

“There’s about 60 or 70 species of fish that now have established populations in Tasmania that used not to be here,” said Craig Johnson, who leads the ecology and biodiversity centre at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania. “You might see them occasionally as sort of vagrants, but they certainly did not have established populations.”

There’s going to be a whole bunch of species here that we expect will just go extinct

But the region’s indigenous cold-water species have no place to go. Animals such as the prehistoric-looking red handfish are accustomed to the frigid water closer to the shore. They cannot live in the deep-water abyss between the bottom tip of Tasmania and Antarctica.

“It’s a geographic climate trap,” Johnson said. Marine animals unique to Australia – the wallabies and koalas of the deep – could easily vanish. “So there’s going to be a whole bunch of species here that we expect will just go extinct. You know, it’s not a happy story.”

Every time he dives for abalone, Rodney Dillon plays his part in what is arguably Tasmania’s saddest story of all.

At 63, he’s getting too old for the occasional plunge. Before a dive on a windy day in September, two people had to wrestle his wetsuit over a thick athlete’s body softened by time.

Dillon persists because diving puts a favourite food on the family table, and, more important, it carries on a dying Aboriginal custom nearly ended by the British crown and the Australian governors it appointed.

Under the water, amid swaying emerald stalks of kelp, Dillon thought that he glimpsed the world his ancestors saw.

“I sometimes got lost in the kelp. I would lose concentration from catching food and go to look, sort of sky-gaze, at the beauty of the light coming through,” he said.

The light dimmed for the natives, known as the Palawa, in the late 1700s, when the British established a penal colony for convicted outcasts at Sydney harbour and looked south for more land to conquer.

Between 4,000 and 7,000 Aboriginals were spread out over Tasmania, then known as Van Diemen’s Land, when the British military arrived with a group of convicts in 1803. Within 50 years, all but 200 of the Aboriginals were dead.

3.3%

of the Australian population identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander

In a history that isn’t widely known in Australia, let alone the wider world, Aboriginal land was seized without a treaty, said Lyndall Ryan, author of The Aboriginal Tasmanians, a history of how the native people met their demise.

When the natives tried to defend the kangaroo hunting and abalone fishing grounds that sustained them, they were routed.

“Genocide was government policy for more than 200 years,” Ryan wrote.

At the time, British archaeologists adhered to junk science that said Aboriginals were the last link between humans and apes.

When William Lanne, the last full-blooded Tasmanian Aboriginal man, died in 1869, a researcher cut off his head, took it to England for study, then displayed it in a museum. After Truganini, the last full-blooded woman, died seven years later, her skeleton was placed on display at a museum in Tasmania against her wishes. “Don’t let them cut me,” she said on her deathbed.

With their deaths, Tasmania declared that Aboriginal Tasmanians were extinct.

Around 1910, after Australia became a nation under the British, officials launched a programme that removed mixed-race Aboriginal children from their mothers.

In his book, Australia’s Coloured Minority: Its Place in the Community, author AO Neville partly explained the young country’s motive. Assimilation of black Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people could be assured only by “breeding out the colour” of their skin.

As a “protector of Aborigines” in Western Australia for 21 years ending in 1936, Neville had a guiding influence on the child removal programme.

Over six decades, welfare workers across Australia took children, some of them at birth, from any parent the state deemed unfit, up to an estimated 50,000. Brown children were placed in white institutions, church social programmes and homes to promote intermixing.

“Generally by the fifth and invariably by the sixth generation, all native characteristics of the Australian Aborigine are eradicated,” Cecil Evelyn Cook, the “chief protector of Aborigines” in North Australia, said in 1933. “The problem of our half-castes will be quickly eliminated by the complete disappearance of the black race, and the swift submergence of their progeny in the white.”

Ancient Aboriginals likely would not recognise the 20,000 or so Tasmanians who currently identify as their descendants. The large majority are white.

Dillon’s great-great-grandmother, Fanny Cochrane Smith, is known as the last speaker of the indigenous Aboriginal language

Dillon said dark-complexioned Aboriginals on the mainland doubt his heritage because of his appearance.

Like most Aboriginals in Tasmania, his skin is pale. His eyes are blue-green, the colour of the sea. White locks atop his head swirl like ice cream.

“People make nasty comments all the time,” he said.

Dillon’s great-great-grandmother, Fanny Cochrane Smith, is known as the last speaker of the indigenous Aboriginal language. He is considered an elder among his people in Tasmania, and he is leading them in speaking out against discrimination.

The Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, formed in the 1970s, is demanding full recognition by the government. Nearly 200 years after the British arrived, Tasmania became the first Australian state to apologise for engaging in child removal and has also given back a small portion of land.

In 2008, then-prime minister Kevin Rudd apologised to the “Stolen Generations”. That year, the state of Tasmania agreed to dole out A$5m to victims and their kin.

At her house in Launceston, Nanette Shaw, a descendant, clings to the traditions of her forebears by fashioning bull kelp into baskets.

Shaw, 66, said she turned to basketmaking to ease the trauma she experienced while growing up as an Aboriginal.

“It centres me,” Shaw said. She suffers from depression and alcoholism, and the craft is her distraction. “I have not been drinking for nearly 10 years. Sometimes the depression takes over, and rather than walk down and get a bottle, I’ll do this.”

But if impacts from climate change worsen, the traits can’t be handed down to children, she said.

The shells are disappearing amid a mix of warming water and pollution. As recently as two decades ago, it was hard to walk on the beach without stepping on them, she said. “Now you’re walking on pure sand,” Shaw said.

Ninety miles away on Scamander Beach, her friend Patsy Cameron found bull kelp to gift to Shaw and several handfuls of jewellery-quality shells.

But it now takes nearly a day to collect them, as opposed to two hours years ago.

“If climate change destroys the seaweed, our shell supply will disappear along with the kelp forest,” said Cameron, 72.

“It’s getting hotter and that heat, it’s affecting not only the giant kelp, but the colour of the abalone is changing,” Dillon said.

“We just take too much out of the Earth and we don’t put it back,” Dillon said. “Australia is one of the worst if you know about coal. How much coal do we need to dig up? And we’re too stupid to see what this is causing ... because we make money out of it.”

And now, Australia is caught in a record-breaking heatwave.

A heartbreaking video went viral late in November, showing a koala bear slowly walked through wildfire.

The marsupial, euthanised days later because its burns didn’t heal, was just one victim of the many wildfires that started burning in the Australian spring and are still going at the start of summer.

At least nine people have died and 700 homes have been destroyed. One woman in New South Wales took a few of her house’s charred remains to Australia’s parliament in early December with a message for prime minister Scott Morrison.

“Morrison, your climate crisis destroyed my home,” Melinda Plesman wrote in bold red letters.

Morrison is an ardent supporter of coal excavation in a country that produced 44 million tons in 2017. Australia is the world’s leading exporter of coal, mostly to Asia, and the fourth-largest producer.

A few weeks before the koala – nicknamed Lewis – was euthanised, the newly reelected prime minister took his advocacy for coal to a new level. He pledged to outlaw environmental demonstrations, calling the protests a “new breed of radical activism” that is “apocalyptic in tone”.

One month later, a Sydney Morning Herald headline described conditions in Australia’s most iconic city as “apocalyptic”, as residents choked in a smoky haze from bush fires. A coalition of doctors and climate researchers declared it a public health emergency.

The bush fires have arrived amid record heat and particularly dry conditions that experts say are being made more common thanks to climate change.

The country experienced a five-day heatwave in the state of Victoria that shattered records. The Friday before Christmas was the hottest December day on record, measuring 47.9C at the Horsham weather station.

Rescuers searching for human survivors in the scorched remains of forests have discovered koalas, a creature found only in Australia, burned to death in eucalyptus trees where they sought shelter. At the Port Macquarie Koala Hospital, where Lewis was put down, the situation was described as “a national tragedy”.

The tragedy playing out underwater is much worse, but invisible to most.

Giant kelp is lovely but fragile. It needs cool, clean, nutrient-rich water to survive, and it’s losing all three

In 1950, giant kelp stretched over 9 million sq metres in a thick band along Tasmania’s coast, said Cayne Layton, a research fellow at the marine and antarctic institute. Today, it covers fewer than 500,000m in little spots on the coastline.

Giant kelp is lovely but fragile. It needs cool, clean, nutrient-rich water to survive, and it’s losing all three.

It is a serious loss. Divers coveted swimming amid plants that grew like the mythical beanstalk to glimpse some of the world’s rarest creatures. Squid fed there, red handfish hid there, spiny pipehorse lounged about, and rock lobster were abundant.

The most recent study – nearly 10 years old – estimated that 95 per cent of giant kelp had been lost to warming and pollution, Layton said, and is probably much worse now.

The less spectacular common kelp, which grows on the coastal slope leading to deep water, is overtaking the spaces where giant kelp grew, Layton said. Along with long, straplike bull kelp that clings to giant rocks near the shore, common kelp appears to be more tolerant to warming temperatures.

But even these species aren’t safe. The warming water has introduced a new plague: long-spine sea urchins, an animal that greedily devours kelp.

A single urchin was found in the cold waters off Tasmania by divers conducting a survey in 1978. Now, there are more than 18 million, according to the most recent survey by the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies.

Sea urchins prefer warm water. They swarm rocky reefs where kelp grows, leaving oceans barren and devoid of life.

Kelp is as important to the sea as forests are to land, said Layton, “so if you can imagine what the world would be like without trees, that’s what a world without kelp forests would be like”.

Scientists say there is only one explanation for why sea urchins migrated so far from their warmer natural habitat near Sydney to the cold waters around Tasmania: the East Australian Current.

The current, made famous in the film Finding Nemo, is fed by a vast stream of tropical water that reaches Australia’s coast after travelling all the way from South America. The water then flows south down the east coast of Australia and then swings back east just north of Sydney.

At that point, the warm-water current splits, with some water flowing southward towards the Tasman Sea in the form of swirls of tropical water called eddies – and this secondary branch has intensified.

The warmer water disintegrated most of the giant kelp over two decades and contributed to the massive, record-breaking marine heatwave of 2015

This extension of the East Australian Current is spewing thousands of eddies deeper southward towards Tasmania, carrying the larvae of warm-water species to places they had never been.

According to research compiled by Professor Gretta Pecl at the University of Tasmania, toxic algae blooms lurk where giant kelp once flourished. Abalone have gone from healthy to “stressed”. The brightly coloured Maori octopus is being replaced by the gloomy octopus, more common to the waters near Sydney. And a yellow-bellied sea snake has migrated to the habitat.

The warmer water disintegrated most of the giant kelp over two decades and contributed to the massive, record-breaking marine heatwave of 2015.

“You can’t say that this event was due to climate change,” said Holbrook, the ocean scientist. “But what you can say is that the intensity was much more likely due to climate change.

“You liken it to smoking,” he said. “If you smoke cigarettes, you increase the likelihood of getting lung cancer.

The marine heatwave left something behind when it finally ended: disease.

A sickening smell at the shallow Pipe Clay Lagoon is how Pacific oyster mortality syndrome (Poms) introduced itself to Steve Calvert.

The syndrome turned his small oyster farm in the lagoon into a mass grave, and the smell of the dead stretched for miles. Calvert lost 75 per cent of his oysters in 2016. Other farmers in the region’s five major farming areas lost nearly 100 per cent of their stock.

Oyster mortality disease had stricken France, China, the United States, New Zealand and even Sydney, but never pristine Tasmania.

“We’ve got a reputation in Tasmania of having pure water and some of the freshest air in the world,” said Calvert’s son, Liam, a manager at the farm. “So that’s part of why there’s an attraction to the Tasmanian oyster, because people think pristine-forest freshness and all that kind of thing.”

Climate change had raised the region’s water temperatures to an ideal level for the contagion. Poms joined warm-water toxic algal blooms as a new threat to the region’s aquaculture and fisheries.

In an encouraging sign that Tasmania’s aquaculture can adapt, scientists had prepared the Calverts and other farmers for the possibility that Poms would strike.

“We’ve been working with industry for quite a long time, and we’ve always had the philosophy that scientists need to know how to farm and farmers need to know how to do science,” said Sarah Ugalde, a research fellow at the University of Tasmania.

Ugalde and her team persuaded the farmers to buy oysters from other areas that survived a disease outbreak. They used that stock to cultivate a disease-tolerant oyster. The Calverts lost about a million oysters but rebuilt the stock with spat – oyster babies – recommended by scientists.

Tasmania’s $25m-per-year oyster farming industry is thriving. The product price, driven up to $1 per oyster from demand during the disaster, stayed the same, helping the Calverts to increase revenue.

“It’s good performance work, and there’s a good return for the hard work,” Steve Calvert said. “We still love this ocean.”

It’s a matter of adapting to a warming world.

“Generally, there’s been a lot of work that’s gone into trying to estimate how fisheries production ... will change with climate change,” said Johnson, the marine institute researcher.

“For southeastern Tasmania, which accounts for most of Australia’s fishery production, the projections are that the fishery production will decline,” Johnson said in his office by the water.

“Like I said, it’s not a particularly happy story.”

The Washington Post’s Juliet Eilperin contributed to this story

©The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments