Extinction of North America’s largest animals likely caused by ancient climate change

Earlier research has suggested pre-historic, big-game hunting humans wiped out large mammals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ancient climate change was likely behind the extinction of North America’s largest pre-historic animals, according to new research.

Earlier studies have suggested that growing numbers of “big-game” hunting humans in the Americas some 14,000 years ago led to large mammals being wiped out.

But the new study, from the Max Planck “Extreme Events” research group in Jena, Germany, proposes that populations of megafauna fluctuated due to climate change.

Around 13,000 years ago populations of creatures such as mammoths, massive ground-dwelling sloths, giant beavers, and a huge armadillo-like species called glyptodons began to drop off. By around 10,000 years ago these creatures, classed as megafauna because they weighed more than 44kg, had vanished.

What happened to these animals has been the subject of intense debate among academics for decades.

Many scientists believed that booming human populations across continents led to “overkill” after many large animals were unable to adapt to these new sophisticated predators.

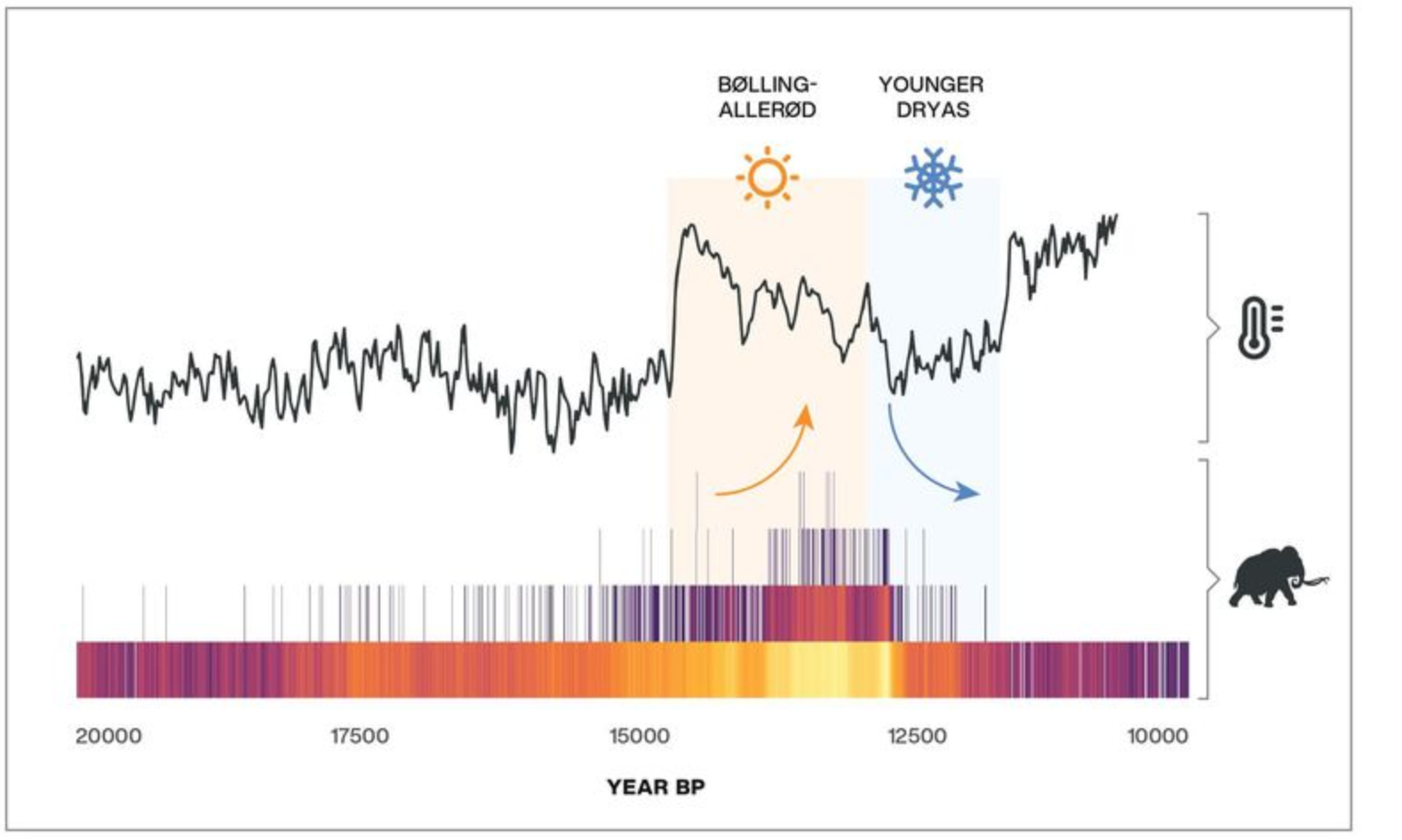

However this theory left some unconvinced. When the extinctions were happening, between 15,000 and 12,000 years ago, two major climatic changes also took place.

Around 14,700 years ago there was a period of dramatic warming. Then around 12,900 years ago, the Northern Hemisphere swung back to near-glacial conditions. The see-saw in temperatures would have caused significant ecological disruption.

“A common approach has been to try to determine the timing of megafauna extinctions and to see how they align with human arrival in the Americas or some climatic event,” co-lead author Mathew Stewart said.

“However, extinction is a process - meaning that it unfolds over some span of time - and so to understand what caused the demise of North America’s megafauna, it’s crucial that we understand how their populations fluctuated in the lead up to extinction. Without those long-term patterns, all we can see are rough coincidences.”

The study, published in Nature Communications on Tuesday, used a new statistical modeling approach developed by W Christopher Carleton, the study’s other co-lead author.

Figuring out what happened to people and animals many millennia ago involves radiocarbon dating, a method to determine the age of prehistoric samples by calculating radioactivity of their carbon content. The idea is that if there is more datable carbon in archaeological and fossil records, it would suggest that more animals and humans were present in a certain place.

The Max Planck research group says the new method is better at accounting for uncertainty in fossil dates compared to established ways. The new method led to the group finding that large mammal populations fluctuated in response to climate change.

And while the study found that while the swing back to near-glacial conditions around 12,900 years ago was the likely cause for the extinctions, humans may have had indirect impacts.

“We must consider the ecological changes associated with these climate changes at both a continental and regional scale if we want to have a proper understanding of what drove these extinctions,” said senior author Huw Groucutt.

“Humans also aren’t completely off the hook, as it remains possible that they played a more nuanced role in the megafauna extinctions than simple overkill models suggest.”

For example rather than simply linking extinction to enthusiastic hunters, factors such as the changes people made to large mammals’ habitats may have played a role.

This article has been updated

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments