Origin of plague causing ongoing 'amphibian extinction crisis' discovered by scientists

Discovery of 'ground zero' for deadly disease has implications for global biosecurity measures

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The origin of a disease that has torn through the world’s amphibian population has been traced to Korea by a team of scientists.

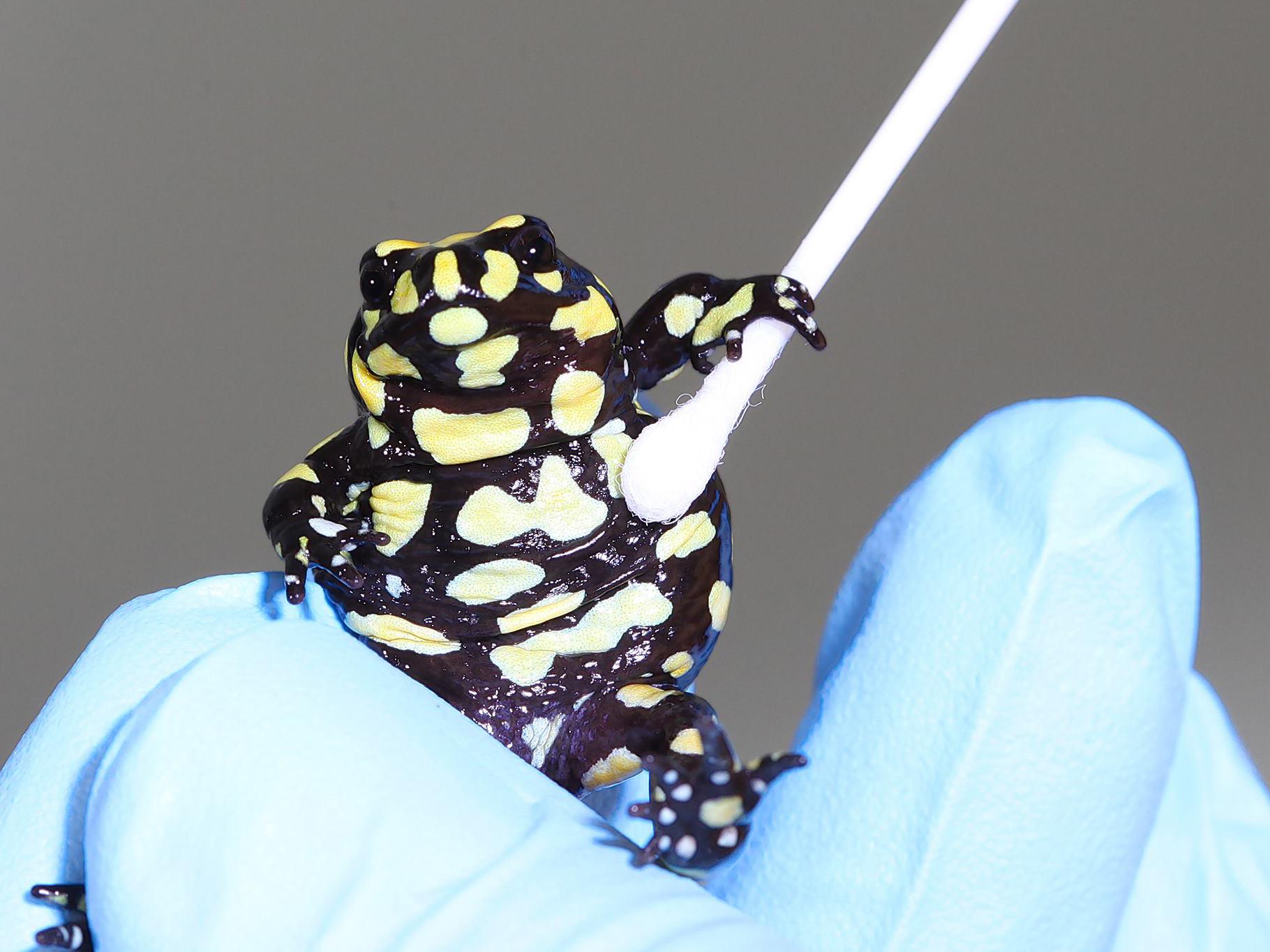

Chytrid fungus is responsible for a decimation of frogs and salamanders that has been going on for decades and is thought to have eradicated over 100 species.

The disease has been found all over the world, but no one has known where and when it first emerged.

Now an international research team has traced the deadly fungus to East Asia and has concluded that the global trade in amphibians for exotic pet, medical and food purposes is behind its spread.

“Biologists have known since the 1990s that [chytrid fungus] was behind the decline of many amphibian species, but until now we haven’t been able to identify exactly where it came from,” said Dr Simon O’Hanlon, a researcher at Imperial College London and lead author of the study.

“In our paper, we solve this problem and show that the lineage which has caused such devastation can be traced back to East Asia.”

The chytrid fungus infects animals’ skin, affecting their ability to regulate water and electrolyte levels and ultimately leading to heart failure.

It can pass between individuals with ease, and some are more affected than others.

For their study, published in the journal Science, the researchers gathered samples of the fungi from all around the world and combined them with an existing database so they had a collection of more than 200 samples.

They examined the differences between the different fungal genomes, and identified four main lineages, three of which were found all over the world.

The fourth was only found on frogs native to Korea.

This finding suggested that rather than dating back thousands of years, as previous work had suggested, the disease expanded its range massively between 50 and 120 years ago, at the same time the international pet trade took off.

Recent research in Panama, where chytrid fungus has devastated local wildlife, suggested some species of frog were developing resistance to infection.

Nevertheless, the disease still poses a major threat, and the new study also uncovered additional strains of the fungus that have the potential to exacerbate the current global epidemic.

These results highlight the importance of tight global biosecurity measures, with team member Dr Lee Skerratt from James Cook University highlighting the strict rules and regulations found in Australia to prevent harm to the local animals and plants.

“We hope this news will push policy change in countries with less strict biosecurity measures,” he said.

Professor Matthew Fisher, from the School of Public Health at Imperial, said: “Our research not only points to East Asia as ground zero for this deadly fungal pathogen, but suggests we have only uncovered the tip of the iceberg of chytrid diversity in Asia.”

“Therefore, until the ongoing trade in infected amphibians is halted, we will continue to put our irreplaceable global amphibian biodiversity recklessly at risk.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments