Outcry over missing Peng Shuai’s #MeToo claim poses new challenge for China

Beijing is seeking to control the narrative around the tennis star as concern grows globally for her welfare, writes Ahmed Aboudouh

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

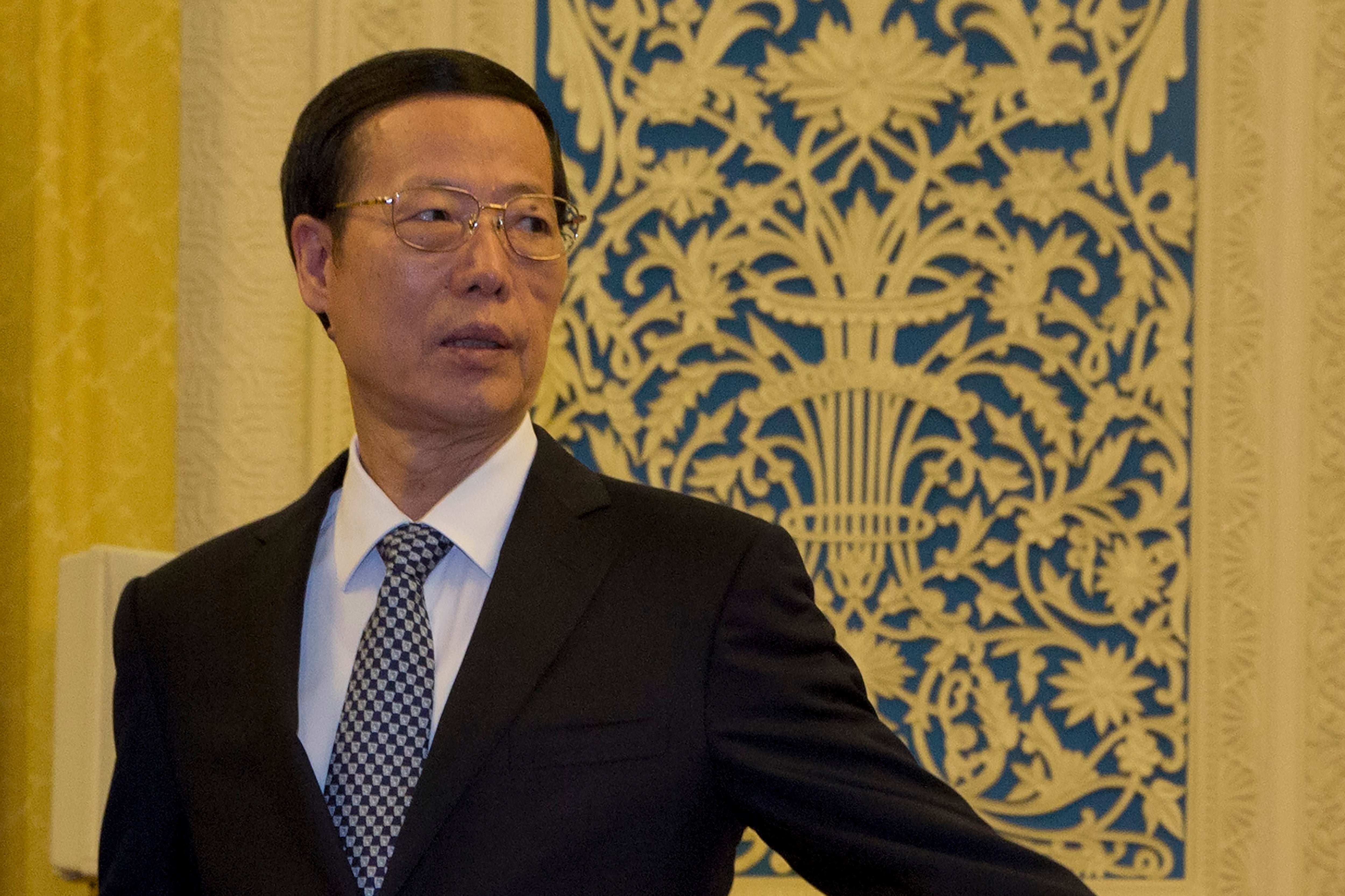

Your support makes all the difference.During his tenure as the Chinese Communist Party’s chief in Tianjin, Zhang Gaoli was a regular at the city’s tennis club where he first met star player Peng Shuai about a decade ago.

Earlier this month, Ms Peng sent shockwaves through China when she accused the former vice premier of sexual assault in a post on Weibo that swiftly disappeared from the social media platform.

She has not been seen or heard from since, and global concerns were growing for her welfare on Wednesday after Chinese state media published a letter purportedly written by Ms Peng, while online posts about her #MeToo allegations were blocked and internet searches were censored.

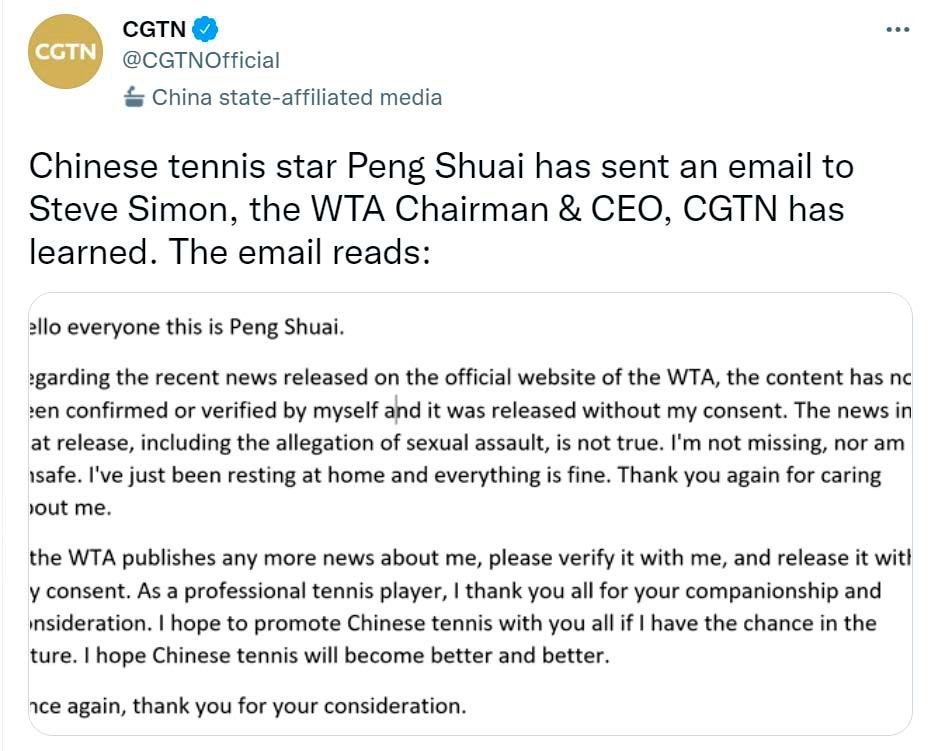

The head of the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA), Steve Simon, said he was worried about Ms Peng’s “safety and whereabouts” after reading the letter that was shared online by China’s CGTV .

The letter, that CGTV claimed was written by Ms Peng, said the allegations of sexual assault were false and that the WTA statement about her missing was released without her consent.

“I’ve just been resting at home and everything is fine. Thank you again for caring about me,” the email said.

Analysts said the tone of the letter suggests that China wants to control the international narrative around Peng and also demonstrate Beijing’s authority over its citizens, even celebrities with global fame.

“It’s not meant to convince people but to intimidate and demonstrate the power of the state: ‘We are telling you that she is fine, and who are you to say otherwise?’,” tweeted Mareike Ohlberg, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund.

This is a common tactic in China’s playbook when it comes to dealing with criticism or dissent.

Government critics, activists, and even actors often go silent or end up missing in China. Even figures who were once among the party’s most trusted can disappear without warning.

On Thursday, Grace Meng, the wife of former Interpol chief Meng Hongwei, lashed out at Beijing in an explosive interview about her husband, who has vanished into China’s penal system after a stunning fall from grace.

She said her husband now calls the government “the monster” because “they eat their children”.

Sometimes, messages by activists and dissidents who disappear in China suddenly emerge online – or are published in the government-controlled media – stating that they are safe.

“Many who have disappeared in China had letters and emails sent in their name or even appeared on television or video to assure people they were fine,” Ms Ohlberg told The Independent. “The goal is to get people to shut up about the case.”

Sophia Huang Xueqin, a journalist and famous #MeToo activist, went missing in September before reports emerged weeks later that police had detained her.

Jack Ma, the billionaire celebrity and founder of multinational technology conglomerate Alibaba, disappeared from the public eye for three months in 2020 after criticising the government’s crackdown on internet giants.

In 2018, star actress Fan Bingbing vanished for four months after a scandal over her tax dealings.

Another actress, Zhao Wei, recently vanished from public view, and her name and work have been wiped from the web in China amid a state crackdown on the entertainment industry and celebrity fan culture.

In the case of Mr Ma, he was effectively tamed as his companies have started to toe the party line on alleviating poverty and climate policies.

As for Ms Bingbing, she said sorry to her fans on Weibo for setting a bad example as an actress and a public figure. Her apology, notably, was full of praise for the Chinese government.

Mr Ma and Ms Bingbing were the epitome of influential figures who failed to embrace the government’s agenda.

But the #MeToo movement – propelled by Ms Huang Xueqin and now Ms Peng – is not an isolated case of criticism, misbehaviour, or vanity. It has struck the core of the Communist Party’s authority, especially given that such a senior former official is under the spotlight.

Unlike other sexual assault accusations involving lower-ranking party leaders, this case has shaken Chinese society. But, so far, Beijing has maintained its silence, as has Mr Zhang.

“Peng’s accusation against Zhang goes right to the heart of political power,” said Seagh Kehoe, a lecturer at Westminister University who focuses on feminism and gender equality in China.

“Peng’s post and the enormous response it has received demonstrates the potential of China’s #MeToo movement to bring about social transformation through consciousness-raising and mass participation by exposing and challenging patriarchy at all levels of Chinese society.”

The timing of the controversy surrounding Peng could not be more unnerving for the party.

It comes days after the opening of the sixth plenary session of the 19th Party Central Committee, which issued the third historical resolution in the 100-year history of the party to consolidate President Xi Jinping’s grip on power.

Support from Chinese netizens for Ms Peng, as well as the outcry from global rights groups and sporting associations, will deal a blow to state efforts to ”tell China’s story” – a narrative pushed by the government months ahead of the Winter Olympics that begin in Beijing in February.

Ms Peng’s case has also thwarted China’s strategy to stifle and stigmatise feminism. Her high-profile status and widespread popularity shield Ms Peng against the typical government-sponsored media accusations of feminist activists being controlled by “hostile foreign forces”.

Instead, the party has always tried to position itself as the sole promoter of women’s rights through stories about female advancement in society at conferences and social events.

“For a party that regularly celebrates its own leading role in liberating women and promoting gender equality, all of this is (yet another) significant blow to their moral authority and political legitimacy,” Kehoe said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments