Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

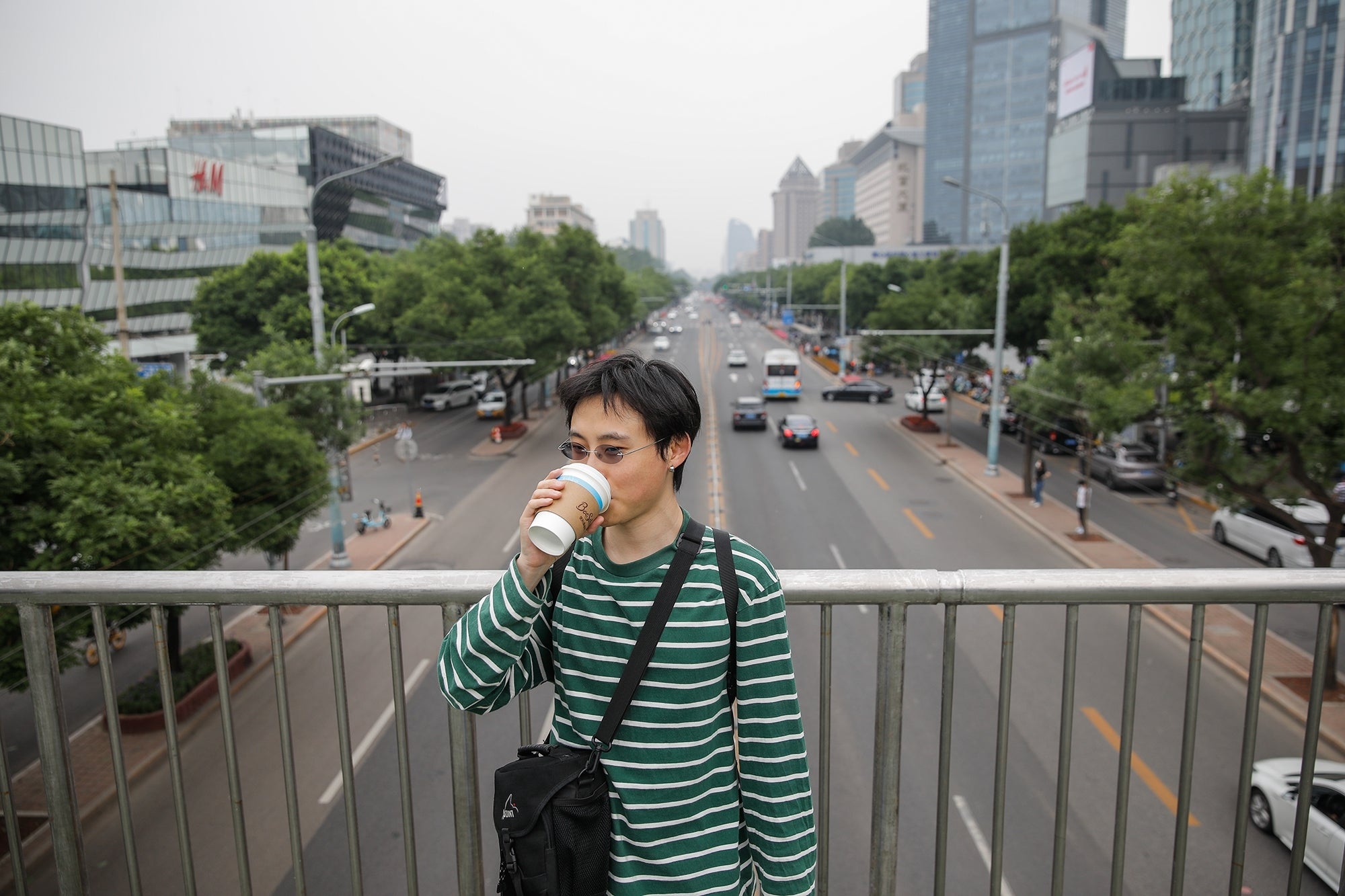

Your support makes all the difference.Millions of young university graduates in China are struggling to find work amid the economy’s sluggish recovery from the Covid pandemic, with some now choosing to leave urban life behind to pursue success and prosperity in more rural areas of the country.

More than one in five people between the ages of 16 and 24 in China are out of work, according to data for June 2023 released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

And with a record 11.6 million college students graduating this year, employment prospects in China’s big cities are looking increasingly slim for many young people.

Urban saturation

Bi Xinyue, 22, who recently graduated with a major in new media, says she has applied to hundreds of jobs without success. She says that the majority of her university classmates are concerned about their future careers.

The jobless rate for people aged 16 to 24 in China for June was 21.3 per cent, according to the NBS, while the unemployment rate for those between the ages of 25 and 59 was just 4.1 per cent.

Given the high unemployment rate for young people, she says she has already given up looking for her “dream job” as “stability is more important”.

But even those of her former classmates who have landed a job complain that their salaries are too low, she says, making life in cities like the capital unaffordable to many young people.

“One of my senior classmates got an internship at a film company last year. The monthly salary was around 5,000 RMB (£562) and now it is only around 3,000 RMB,” Bi explains. According to NBS figures for 2021, the average monthly salary in Beijing was 16,220 RMB.

Another recent arts graduate, Zhang Siyuan, 24, says he has been unemployed for nearly eight months after only receiving offers that he thought were underpaid or did not match his professional qualifications.

“Many of my peers in college haven’t found a proper job after graduation either, they also complain about job offers which are much lower than their expectations,” he says.

The job market in China’s metropolises is pushing many young people to abandon city life, following president Xi Jinping’s call in December 2022 to “revitalise the rural economy”.

Rural revitalisation

Wang Bangle, a 26-year-old university graduate, has decided to return to Xiaogou, a remote mountain village near Ankang, a city in Shaanxi province in central China.

After leaving the area to get a degree in marketing, he got a job after graduation working as a salesman in Chengdu, in Sichuan province.

But he says his monthly wage of just 3,500 RMB was not enough to live in the bustling provincial capital that is home to over 16 million people.

With a low salary and limited job prospects, he returned to his hometown in Shaanxi to set up his own business in 2022.

“I just want to go back to my hometown and build it well. Our purpose in receiving higher education in the city is not to escape from rural areas, but to serve the countryside in a better way, while building our home village into a better place,” he says.

While many of his friends from Chengdu understand why he has made the move back, his family, on the other hand, is taking it as a setback.

“They think that returning to the countryside has no future. Even my brother said ‘If you return to your hometown, attending college will have been in vain.’ Most people here think there’s no future in the village for young people,” Wang explains.

He took out a loan of 50,000 RMB from the village bank, and now, six months later, operates a henhouse with about 300 chickens and a tea plantation.

Wang hopes to earn around 20,000 RMB in the first year, before setting his sights on expanding his chicken feed business.

The biggest challenges, he says, are the lack of funds or incentives from local authorities, as well as a shortage of manpower.

“There are only a few young people I know who decided to come back to the village and set up a business like me,” Wang says. “There should be some young people coming back to help develop their own village – if not me, who will?”

EPA

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments