Paper chase opens chapter on history

THE ARTICLES ON THESE PAGES ARE PRODUCED BY CHINA DAILY, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CONTENTS

It was a feat that would have made any detective or researcher proud. Fragments of information have been painstakingly restored to shed light on a fascinating era. After more than a century, scattered ancient documents marking cultural exchanges along the Silk Road have been reunited in a digital form and finally revealed to the public.

A comprehensive database of the Dunhuang manuscripts was published online by Dunhuang Academy in Gansu province on August 19. It includes their basic information, digitised images, transcripts of the full texts and related documents of academic studies.

“Through this full information bank of Dunhuang documents, their data can be accessed by the world’s academia,” said Ma De, a researcher with Dunhuang Academy who is the leading expert of the database. “Different fragments of related work can also be searched in the system.”

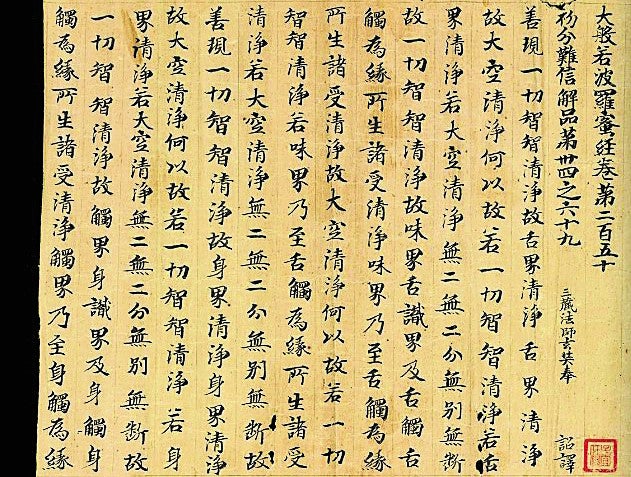

In 1900 a Taoist monk stumbled upon many precious ancient manuscripts and documents, ranging from the 4th century to the 11th century, in a grotto among the Mogao Caves, spanning the cliffs of Dunhuang in the west of Gansu province. That grotto, today coded No.17 Cave in Mogao, is commonly called “the library cave”.

The findings were later collectively known as the Dunhuang documents and are crucial references for the study of history, archaeology, religion, language and other fields, not only in ancient China, but also other regions in East, Central, and South Asia.

However, China faced a deep social crisis around 1900, and the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) government thus had little available resources to safeguard the new discovery in a timely fashion. Numerous Western scholars and amateur explorers swarmed to the Mogao Caves after realising the true significance of this trove, leading to many of the pages ending up overseas.

The caves were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1987, one of the earliest entries from China. Nevertheless, losing text treasures remains a lasting regret for guardians of this cultural wonder.

It is estimated that about 70,000 pieces of Dunhuang documents survive worldwide, only about 20,000 of them in China, and the rest in dozens of institutions in countries such as France, Japan, Russia and the United Kingdom. The world’s oldest known print work, the Diamond Sutra from the year 868, which was found in “the library cave”, is now housed in the British Library in London.

No uniform worldwide catalogue of these documents has been established. Consequently, a project was started in 2012, seeking to introduce a system to digitally categorise the collections of Dunhuang documents in institutions at home and abroad.

It was jointly led by Dunhuang Academy, an institution in charge of protecting and studying the Mogao Caves and several other key grotto sites in Gansu province, and a computing science team of Zhejiang University in Hangzhou.

According to Ma, collected Dunhuang documents worldwide can be realised through the new digital platform, working with institutions such as the National Library of China, the British Library, the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, the French National Library, and so on.

For instance, the project registering new data of Dunhuang documents in France is continuing. It is also a preparation for the upcoming publishing of the full collection of Dunhuang documentation.

“Physical duplicates of the relics from ‘the library cave’ can also be kept as properties of the Dunhuang Academy, and serve for studies and publicity of cultures of Mogao Caves in a long term,” Ma said.

Rong Xinjiang, a history professor at Peking University, said the manuscripts provide key complements to grand pictures of official historical recordings.

“Many Dunhuang manuscripts recorded folk stories, and, surely, they can replace history books,” Rong said. “But these raw materials bring us a perfect perspective to observe the original facets of a society.

“Beyond the orthodox historical recordings on politics, dynastic rise and fall, as well as wars and conflicts, in the manuscripts we can see the ‘ordinary’ history of people’s lifestyles and ideas, which are closer to the truth of history per se.”