Beauty of reduction

THE ARTICLES ON THESE PAGES ARE PRODUCED BY CHINA DAILY, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CONTENTS

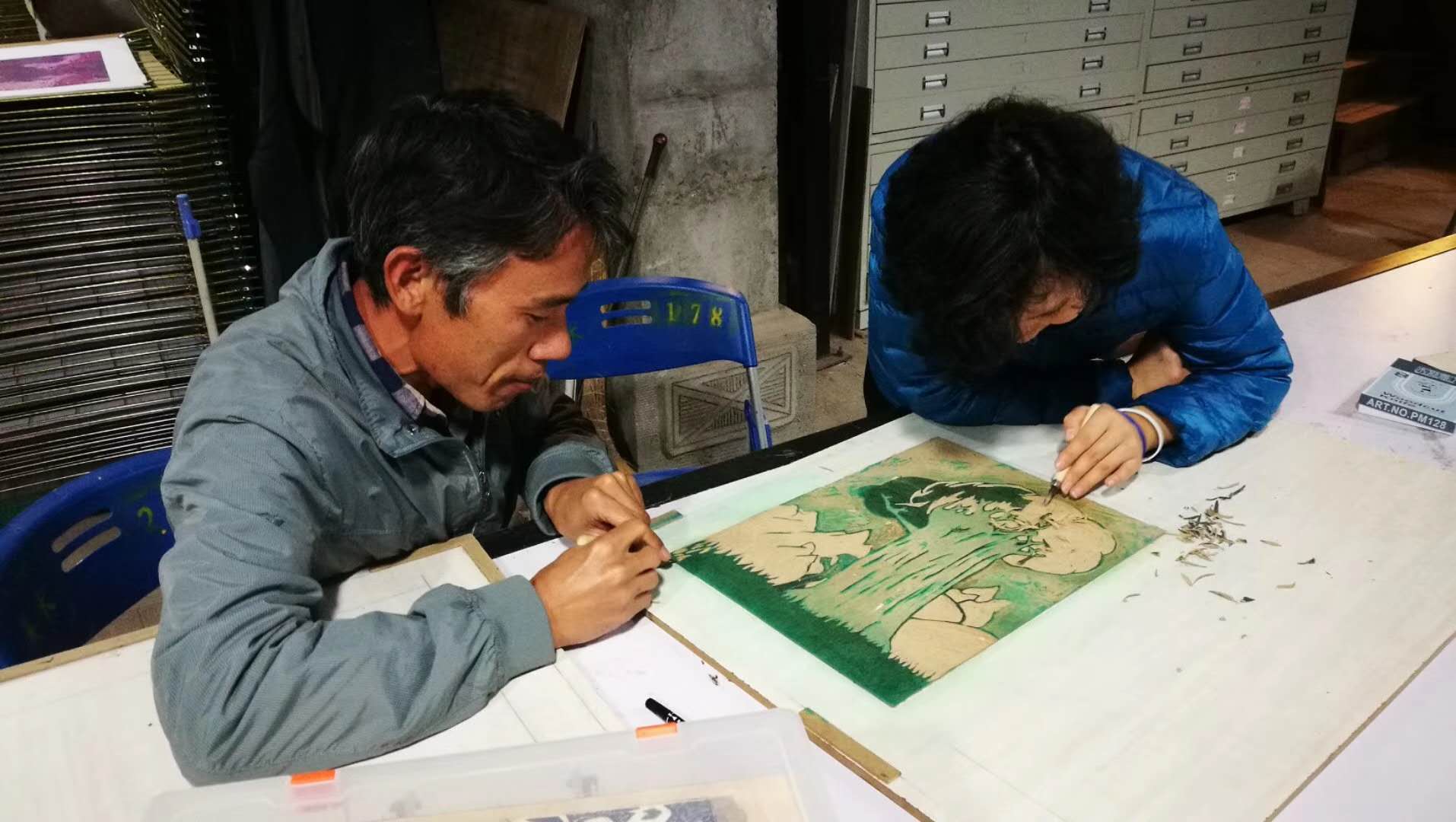

The group of artists, struggling to make ends meet, were faced with a conundrum. While their speciality, traditional woodblock printing, was highly satisfying spiritually, it exacted a heavy toll on them both physically and financially, as well as on their environment.

That’s because the artistic technique requires a single wooden layer for each colour that goes into these multicoloured works.

It was in Pu’er, Yunnan province in the 1980s, and the artists embarked on a quest to discover a technique that would vastly simplify their task: a single wooden board carrying many different colours. Soon, they would come up with a style of woodblock art that would revolutionise their art and solve their financial woes.

In fact it may not have been quite as revolutionary as it seemed to them, for decades earlier another artistic master, Pablo Picasso, had played with the same idea in doing linocuts.

“To me a picture has always been a sum total of destructions,” he is quoted as saying.

In his exploration of the art he eschewed multiple blocks in favour of a single block that he continuously carved into while pigmenting and printing the evolving images. This dynamic process of carving and deconstructing gave birth to what we now know as destructed print, or reduction print.

Leng Guangmian, chief of the reduction woodblock print studio and the teaching base of Pu’er University’s fine art students, says he first encountered the technique at Pu’er University in 2003.

“I had experimented with various painting techniques such as oil painting, wash painting and watercolour sketching outdoors,” he said. “However, I ultimately returned to reduction woodblocks because its artistic language resonates most with my expression.”

A reduction woodblock print is characterised by three things, he says: its unique layered texture; harmonious colour blending; and the unpredictability of the production process.

In contrast to traditional woodblock printing, in which colours are sequentially pressed onto paper from different boards, resulting in defined colour edges, reduction woodblock are printed and simultaneously cut into the boards.

This dual action creates a textured colour presentation and smooth colour transitions, and because the boards are ultimately destroyed and discarded, the process is largely unpredictable and utterly irreversible.

Leng’s reduction woodblock print studio is in the village of Nakeli, a key stop on the Ancient Tea Horse Road and now a popular tourist destination.

“Nakeli and Pu’er are holy lands for artists to paint from life,” Leng says. “There are many ethnic minority settlements where the most primitive characteristics of clothing, language and other ways of life thrive to this very day.”

The name Nakeli, derived from a minority language, means a fertile field by the bridge. More than 60 per cent of its residents are from minority ethnic groups including Hani, Yi, Dai and Lahu.

Reduction woodblock is closely linked with the ethnic and native culture of Pu’er over 40 years, marked by a well-known Zheng Xu work, Lahu Human Scenery, portraying the traditional lives of the Lahu ethnic group. In 1984, the work was honoured with the Golden Prize at China’s sixth National Exhibition of Fine Arts.

As the village embraces rural tourism, the reduction woodblock print studio has become a thriving centre for farmer artists. Hundreds have graduated over the years, venturing into the world of woodblock art, and they have prospered financially.

Tao Shuangquan, a farmer who had had no formal art education, created popular horse caravan prints after a month of training in a woodblock print studio, and his prints became wildly popular.

Prints measuring 15.8 inches x 11.8 inches take one or two weeks, with each reduction woodblock yielding about 12 copies sold at the equivalent of up to $40 (£32) a piece, greatly increasing local villagers’ incomes.

“Farmers’ paintings are boldly expressive, offering a unique perspective on farming, daily life and traditions,” Leng says. “They employ vivid shapes and colours freely, creating dynamic compositions.”