Three blind mice: Children’s song or lesson in violent revenge?

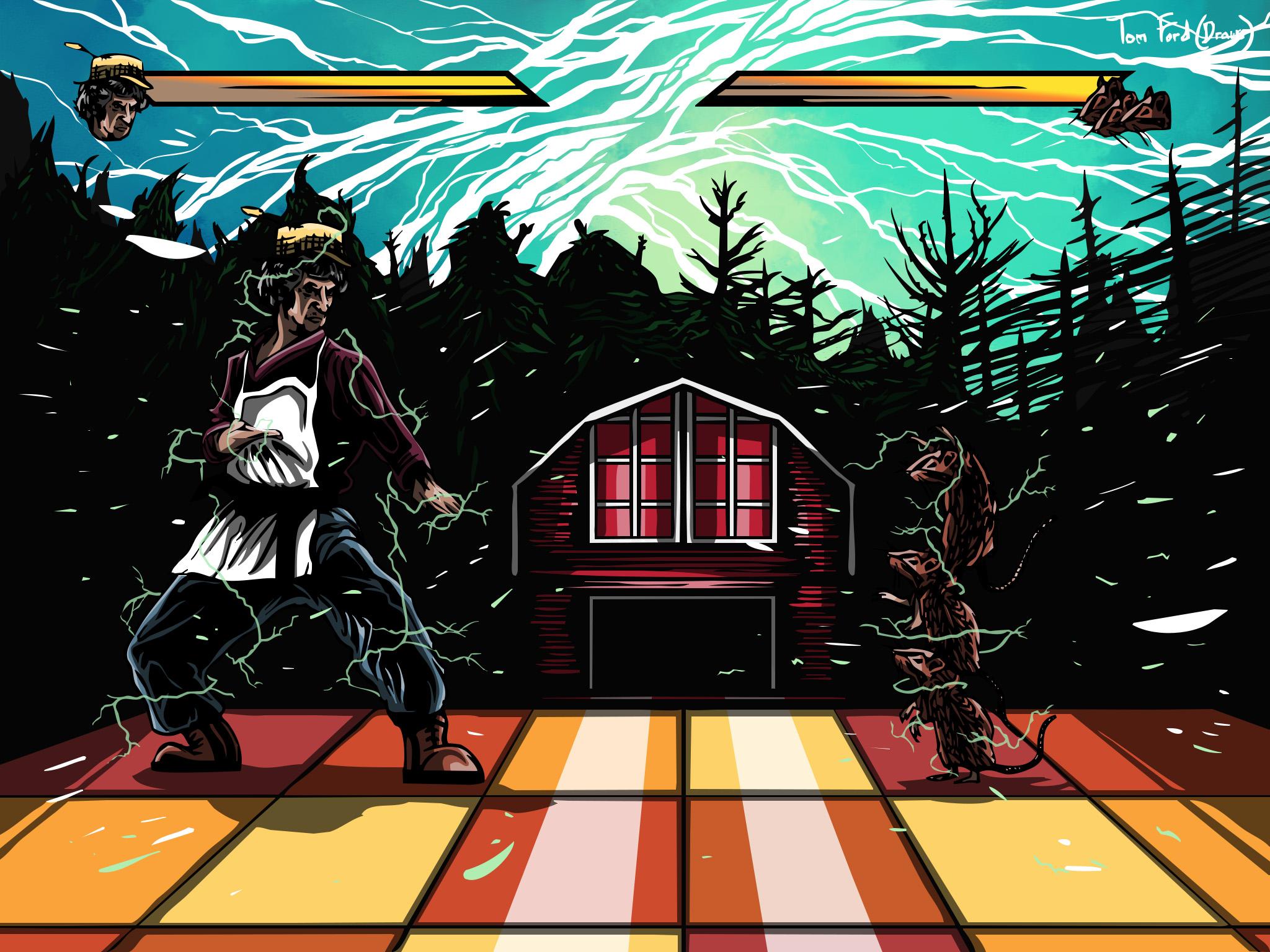

The Outsiders: For the latest piece in his series, comedian Dan Antopolski explores the dark meaning behind one of our favourite nursery rhymes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Not to make a fuss but I play the piano. I have since I was a little boy. I play the saxophone as well but not nearly as well – if that makes sense. When you are starting out on your musical career, ie being forced to take music lessons by your school or your parents, it can take a few goes to find the musical instrument that best suits your temperament. Before the piano I tried the violin, but I found the scratchy noise I was making so unendurable that I begged my mother to let me stop. Come to think of it she agreed quite quickly.

Like many young musicians though, my first instrument was the recorder and my first tune was that classic of English folk horror, Three Blind Mice. The joy of playing it on the recorder rather than singing it was that I did not have to watch the mental movie conjured by the grisly lyrics, in which the eponymous rodents run after the farmer’s wife, who cuts off their tails with a carving knife, sparing their lives with a curious and unsettling restraint.

It is a traumatising song for young children to be made to sing. Not only is the violence shocking – both the overt severing of the precious tails and the vividly implicit bleeding of the stumps – but the motives of all parties are atypical and opaque, lending the scene a certain awful madness and filling the listener with nameless dread. Why are the four of them behaving this way?

Normal mice evade humans, they do not chase them. Normal farmer’s wives do not flee mice, they stand their ground. Yet we are told that the mice are running not “at” but “after” the farmer’s wife: she is not a static target but a receding one, ergo she fears the mice, at least before she gains her weapon from the knife rack and is emboldened to retaliate. But why?

Are these mice aggressive because they are rabid? If so, their small size will be no factor if the frontrunner manages to nip the woman’s ankle. The farmer’s wife will bite the farmer when he returns from ploughing and soon there will be an epidemic. Once the military have got involved, a missile strike may be ordered by the top brass, cratering the farm and irradiating the surrounding Norfolk countryside, which you may feel is the last thing it needs.

Their shared blindness is surely key. Are they blind from birth, in which case they will be siblings sharing a common genetic factor – and some family drama that drives them? Or are they all blind by the same violent misadventure?

So she may indeed be running away from them in a rational desire to avoid rabies. This certainly seems more likely than that such an experienced peasant would be merely afraid of mice, as a city dweller might be. In any case, the brutality with which she imminently amputates their tails must put paid to any notion of phobia.

On reflection though, we also may be inclined to dismiss the rabies theory for literary reasons. The mice are blind – narratively they have enough going on without needing rabies as well: that would only diffuse the storytelling. This song has been in common usage for a long time; we can trust that the blindness is distinctive enough a quality in our mice to hold our interest for the short duration of the story: rabies would be overkill. No rabies.

Those causes eliminated, we must now consider whether the mice have a good reason to chase the wife. Their shared blindness is surely key. Are they blind from birth, in which case they will be siblings sharing a common genetic factor – and some family drama that drives them? Or are they all blind by the same violent misadventure?

And here we have it. The mice have been blinded by the farmer’s wife in a previous encounter and this is their doomed revenge attack! Three Blind Mice is not Star Wars, it is The Empire Strikes Back. The blindness of the mice is the backstory!

O villain! This wife is a monster for the ages, taking first their sight and now their balance. Next she will come for their whiskers and then their noses, never granting them merciful death but sadistically maiming them by degrees. And why begin with their eyes? Because they had seen something they should not have seen…

Why not cut out their tongues then? Because the blinding is a punishment, not a cover-up. The brazen wife is not afraid that the mice will tell the farmer about her romps in the barn with the stable hand. Even if they could speak English at an intelligible pitch, it would be her word against theirs; no husband would credit their shrill hearsay over his wife’s solemn testament. She is fully secure in her power base. Rather, her controlled violence is purely symbolic – a message. A message of dark power, to all the animals, that she does what she pleases, like that Cersei Lannister off of that Game of Thrones!

I did not seek to draw these conclusions from the lyrics to Three Blind Mice, they were inescapable and I hate being right about them. I hope you don’t sing it to your children. And we all hope that Cersei gives the carving knife a good wash before doing any more food preparation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments