Those who think Marlowe co-wrote plays with Shakespeare may Kyd themselves

Researchers have decided Christopher Marlowe’s work on Shakespeare’s plays was extensive enough that he deserves a credit in future editions, but just how reliable is the technology used to come to such a grand conclusion? Darren Freebury-Jones questions the move

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

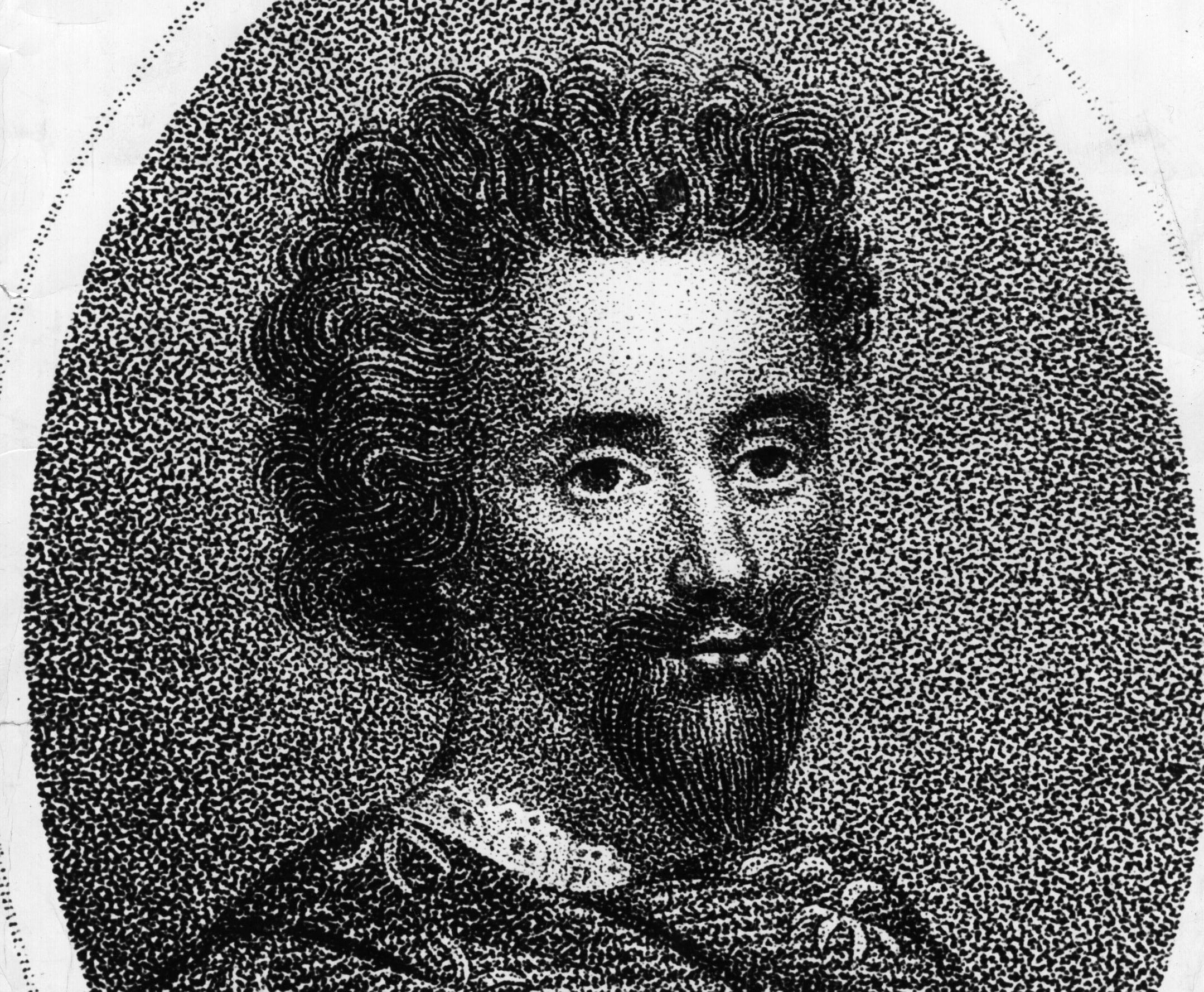

Your support makes all the difference.Christopher Marlowe, 16th century playwright and contemporary of Shakespeare, is to be given co-writing credit alongside Shakespeare for the Henry VI trilogy in the New Oxford Shakespeare edition of the Bard’s collected works. This decision follows computerised textual analysis of the plays by a group of researchers led by Gary Taylor of Florida State University – techniques which have also identified Shakespeare’s “literary fingerprints” in the domestic tragedy Arden of Faversham.

Arguments over the authorship of these plays have been bandied about by generations of scholars, but could current advancements in technology finally have put paid to doubt?

As an attribution expert who has devoted years to examining the authorship of the Henry VI trilogy, I am uneasy about these headlines. Unfortunately, while statistical analysis, like literary analysis, can aspire to an objective viewpoint, it also relies upon subjective interpretation. Taylor and colleagues don’t appear to have paused to consider whether individual words, denuded of their linguistic context, can be relied upon in analyses of early modern plays – a genre that contains a multitude of characters, each of which speak with individualised voices.

Can the mere regularity with which certain words and phrases appear in the text really distinguish between different authors – considering at the time of writing allusion, parody and appropriation were rife? Shakespeare borrowed words and phrases from Marlowe’s plays. Marlowe borrowed phrases and images from Shakespeare, and also from his fellow dramatist and lodger, Thomas Kyd, who in turn borrowed phrases from him. Matters are complicated further by the fact that there are many other hands – compositors, editors, scribes – involved in the creation of the folios through which the plays have survived the centuries to reach us today.

As the scholar Muriel St Clare Byrne demonstrated in her 1932 work Bibliographical Clues in Collaborate Plays, the number of parallels alone cannot be used to distinguish authors. Scholars must also examine the qualitative aspects of shared phrases – and whether these reveal distinct combinations of both thought and language, indicative of a single mind. Reading-based methods still have a place in modern authorship studies but, unfortunately, all too many scholars are convinced by studies that take a number-crunching approach to play texts.

By whose hand?

Kyd is very much the ghost at the feast here. One of the most famous dramatists of the period, he revolutionised tragedy as a genre and paved the way for Shakespeare’s dramaturgy with his Spanish Tragedy. Contemporary writing and allusions indicate that he wrote a Hamlet play, now lost, while evidence drawn from the characteristics of the text demonstrates that he was responsible for the anonymously-authored Elizabethan play King Leir, which served as a source for Shakespeare’s King Lear.

Kyd had considerable influence on Shakespeare, and also collaborated with him on Edward III. But due to the small number of acknowledged works, his name is not as well-known as that of Marlowe or Shakespeare. So the notion that it was the more infamous Marlowe – secret agent! Murdered! Conspiracy! – who collaborated with Shakespeare has perhaps greater appeal to would-be buyers of the forthcoming New Oxford Shakespeare edition.

However, there is firm evidence that Kyd collaborated with the pamphleteer and playwright Thomas Nashe on the play that became Henry VI Part One. This play was an attempt by theatrical company Lord Strange’s Men to capitalise on the success of Shakespeare’s two-parter dealing with the young king’s disastrous reign. All three Henry VI plays were acquired by the Chamberlain’s Men, for whom Shakespeare seems to have added a few scenes to the first part, perhaps in an attempt to link it with his two plays on the Wars of the Roses.

Different approach, different answer

There are methods that have proven effective in distinguishing authors, such as analyses of verse style (such as the rates in which dramatists employed an extra syllable at the end of lines), prosody (pauses and the positions they appear in the verse), and collocations of words and phrases.

Taken together these support the theory that it was Kyd and not Marlowe who had a main hand in writing the first part of the trilogy. These traditional methods also support the hypothesis that Shakespeare wrote Henry VI Part Two and Part Three for Pembroke’s Men without the aid of another dramatist. But even so, echoes of his contemporaries’ works abound in these texts, as we might expect in drama of the period.

Attribution experts Marcus Dahl and Lene Petersen have also analysed frequencies of single words in Shakespeare’s texts, but they have reached entirely different conclusions to the New Oxford Shakespeare team. Martin Mueller of Northwestern University has conducted quantitative analysis of both common and unique phrases that shows that again it is Kyd’s written characteristics that appear in Henry VI Part One and Arden of Faversham, whereas there is very little verbal evidence to support crediting Shakespeare as co-author of Arden of Faversham.

So in short, while it makes for good headline material, claims of co-authorship for Marlowe are only one side of an involved and long-running argument. In my view, these new attributions are unlikely to withstand close scrutiny, but one hopes that the ensuing discussions will help bring Shakespeare’s contemporaries such as Kyd to wider public appreciation.

This article was first published in The Conversation (theconversation.com). Darren Freebury-Jones is a research fellow at Cardiff University

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments