Yvonne Stagg and the Wall of Death: The Queen of Dreamland

As the proprietress of her own Wall of Death – and the star of the show – Yvonne Stagg was a 1960s success story. With the Margate attraction reopening this week, Lois Pryce charts the rise and fall of the girl on the motorcycle

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Margate's fortunes are on the up. After decades as a low-rent seaside resort, the town's famous Dreamland amusement park is set for a grand re-opening this weekend. Tracey Emin will be pleased to see the revival of her old stomping ground – indeed, she donated artworks to be auctioned to raise funds for Dreamland's revival. She has often spoken about the days she spent as a child and a teenager haunting the park and its rides and her regret at its dilapidation. "I grew up in Margate with the Golden Mile. The neon and the lights always seemed like magic to me. I really wish that Margate could be relit again," she said.

Emin might have put Margate on the map as the town's official celebrity bad girl-done-good, but 1970s Dreamland was also home to a lesser-known female trailblazer whose fortunes took the opposite trajectory of Emin's.

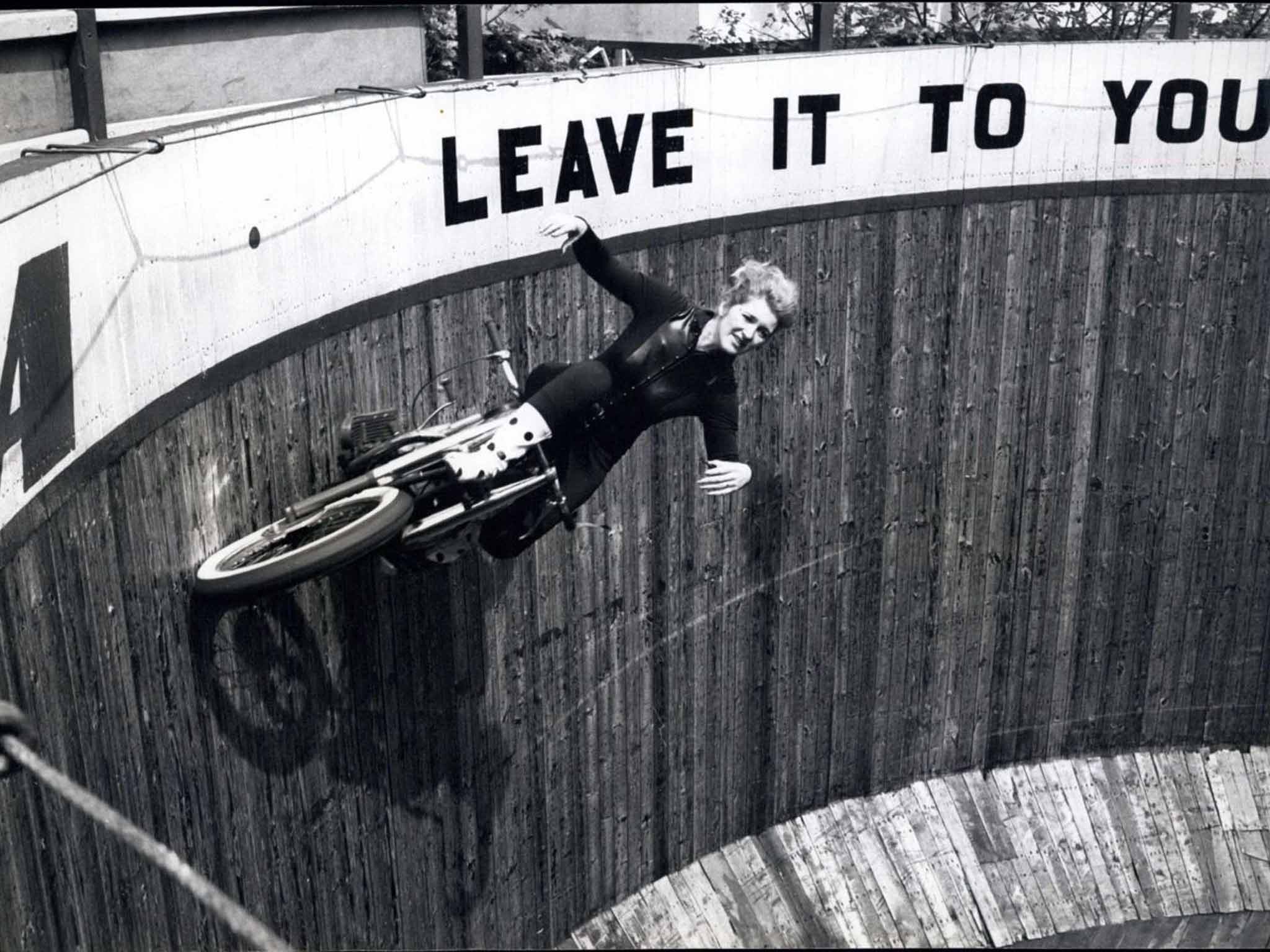

Yvonne Stagg was the owner and celebrity rider of Dreamland's Wall of Death, the UK's first and only female owner of the attraction.

Originating in the US and introduced to the UK in the 1920s by the showman George "Tornado" Smith, the Wall of Death is a hollow wooden drum, approximately 30ft in both diameter and height, that sees motorcyclists riding around its interior and performing stunts at speed, seemingly defying gravity but held in place by centrifugal force.

The Wall of Death was Dreamlands' top sideshow, guaranteed to draw hordes of local kids and out-of-town visitors on their seaside "beanos", all eager to witness the thrills – and occasional spills – of the daredevil motorcyclists tearing around the Wall on their ear-splitting, beat-up old bikes. As well as riding the Wall herself, Yvonne had a team of riders in her employ who would perform throughout the day during the season. Punters would queue up for the hourly shows, lured in by the "spieler" at the entrance, hollering lurid descriptions of the sights and sounds that awaited the audience, should they dare enter.

With her name emblazoned across the awning, and her team of side-burned male riders, Yvonne was the queen of Dreamland. Blonde, bold and infamous for teetering across the fairground in her high-heeled white boots, carrying her two beloved Chihuahuas, she would straddle her 500cc BSA and launch herself up and around the Wall. The boys and girls of Margate couldn't get enough. In an era when women were starting to reject the conventions of society, here was their very own local heroine.

As a rider of vintage motorcycles and a fan of all things fairground related, I have had a long fascination with the Wall of Death and particularly with Yvonne Stagg. I first heard about her many years ago, from a friend who grew up in Margate in the 1970s, and spent his youth getting up to high jinks at Dreamland. He would recount tales of Yvonne's antics, and how her hard-living, glamorous daredevil image endeared her to even the toughest boys in town. After reading Riding the Wall of Death by Allan Ford, one of Yvonne's former riders at Dreamland, I wanted to learn more.

Unlike many "carnies", Yvonne was not the product of a fairground family, I learned from speaking with Allan Ford. But her upbringing had acquainted her with the seedier side of showbiz. Her mother ran the Cedars Club in Sittingbourne, Kent, a renowned jazz venue in the 1950s. To offset her domestic life, Yvonne was sent to a convent school, only to return home each evening to a fug of cigarette smoke and booze, a lonely witness to the comings and goings of her mother's "disorderly house".

It was no great surprise that she left home as a teenager and headed for London, landing herself a job as a secretary.

But London in the early 1950s must have seemed grey and dull, still being in the grip of rationing. The Festival of Britain was the only glimmer of excitement in the post-war dreariness and Yvonne got in on the action, selling candyfloss at the festival's funfair in Battersea. It was here that she first set eyes on a Wall of Death. Fearless young men on deafening motorcycles raced round and round a vast wooden cylinder, casually sitting side-saddle or riding with no hands, swooping up to the amazed audience on the viewing platform.

When one of these stuntmen caught Yvonne's eye and invited her to take a whirl, sitting on his handlebars, she jumped at the chance.

Her life changed forever.

From then on she used every spare moment between shifts to "ride the bars". It was not uncommon for a Wall of Death to feature a young woman as a glamorous assistant but there were occasional female riders, too, and Yvonne decided that she was destined to be more than just a pretty face. She begged the proprietor to teach her to pilot her own bike. Within a year she was on tour around the UK, performing with a travelling Wall of Death.

The Wall of Death was a global phenomenon in the 1950s, with both permanent and travelling Walls in the USA, Germany, Russia, Australia and South Africa. It turned out that there was always a job for a good-looking, young female rider and Yvonne began working the seasons in Germany where, I learned from Ford, she met her future husband, a fellow Wall rider, Gustav Kokos. But domesticity was not calling yet and when the opportunity came to take a Wall to newly independent Sierra Leone in 1961, she joined the team and set sail.

It was supposed to be a grand adventure but the scheme was doomed from the start. The man behind the plan was Peter Catchpole, a well-known operator and expert Wall of Death rider who, while making his fortune in property and amusement arcades, never quite got the lure of the Wall out of his system. He made a habit of appearing and disappearing at opportune moments, setting up fairgrounds and Walls all over the world – from Merseyside to Nigeria – throughout his colourful career. But in Sierra Leone, it soon transpired there was no money to pay the riders and the fairground folded. Yvonne and two colleagues found themselves out of work, stranded and broke. As I know from experiences, being alone in darkest Africa with just a motorcycle to your name requires you to think on your feet.

Ever resourceful, the trio turned their hand to diamond prospecting, but things deteriorated when Yvonne contracted malaria and a serious inner-ear infection. In the end, one of the riders took a job as a mechanic in order to fund their passage home – but tragedy struck when he too became ill, and suddenly died. With no money to repatriate his body, Yvonne had to bury her friend and colleague in an alien land. Their Wall of Death received the same fate, being dismantled by Yvonne and concealed somewhere in Sierra Leone. (The location remains a secret to this day.) Eventually, though, after scraping her fare together, she made it home, licking her wounds but determined to stay in the game.

She took a job riding Tornado Smith's Wall at Southend's Kursaal amusement park, where she picked up a following of fans, and for a while it seemed as though her fortunes had turned. She settled down with Gustav Kokos and, when Smith retired and put his Wall up for sale in 1965, she snapped it up, renaming it Yvonne Stagg's Wall of Death and establishing her place in fairground history.

Dan Hicks, one of her riders at this time, tells me that he remembers her as being "exuberant, with a zest for life"; and although she was considered shrewd in business, "always pleasant and helpful, with time for other people". Jim Murphy, who also rode for her throughout the 1960s, agrees. "She was considerate and friendly. But she was no mug," he says. "She could look after herself."

In 1974 the Kursaal closed and Yvonne moved her Wall across the Thames estuary to Margate and a new home at Dreamland. As the UK's first and only Wall of Death proprietress, Yvonne, now 37, became something of a local celebrity in Margate and beyond. She was always ready with a quotable line and a dashing picture, and was the obvious go-to girl for the press and media. To the outside world she was riding high, but beneath the roar of the bikes and the bright lights of the fairground a very different story was unfolding.

Despite having stated, aged 30, in a national newspaper interview that she couldn't imagine herself settling down "with kids hanging around my apron", she and Gustav had married and in 1966 they had a daughter, Minka. Yvonne was performing on the Wall of Death until the day before she gave birth and was back in the saddle as soon as possible. When I spoke to Minka, she said one of her earliest memories was of being photographed by the Daily Mirror aged six, riding the Wall on her mother's handlebars with a rope tied round her waist.

This was the early 1970s and while the feminist movement was shaking up the status quo, Yvonne was learning the hard way that juggling motherhood, marriage and a business as physically gruelling as the Wall of Death was a tough task. There were other factors working against her, too. The inner-ear infection she had contracted in Africa had affected her balance, adding a further challenge to an already demanding job; the malaria also made regular recurrences; and on top of her personal problems, the Wall of Death was no longer paying the bills.

The times were changing at the British seaside. The mass coachloads of inner-city day trippers were dwindling as car ownership increased, and the era of Wakes Week, when entire factories decamped to the coast for their summer break, was long gone. The 1960s had seen the advent of cheap package holidays abroad and Brits were eagerly swapping Margate for Malaga. The English seaside resort was fast becoming yesterday's news – a faded, old-fashioned way to spend a summer holiday.

The local Margate youth still turned out for Yvonne at Dreamland, but her appearances were becoming more erratic as she began drinking heavily to relieve the pressures of her lifestyle and a mounting debt problem. Jerry DeRoy, a veteran Wall rider who worked with Yvonne in Germany, remembers her as someone who lived beyond her means. "She bought herself a pair of expensive boots, white leather with black polka dots," he tells me, "and she was always showing off about having a heart-shaped waterbed specially made for her!"

At Dreamland her daily teeter across the fairground was becoming a stagger, the result of her inner-ear problems combined with a daily bottle of tequila, according to Allan Ford, who was riding for her at the time.

"She became increasingly unreliable," he recalls, "She wouldn't turn up, or she'd be late and I would have to go up on my own. Sometimes she would go up drunk and fall off her bike. I was holding the whole thing together but I couldn't say anything, I was young and I was working for her."

Motherhood and marriage were proving particularly trying and Yvonne's approach to parenting largely consisted of leaving their daughter with two older female neighbours. The strain of domesticity was taking its toll and in the winter of 1975 Yvonne left Gustav doing some essential maintenance at Dreamland and returned to Southend where she sought out new thrills, beginning an affair with an Irishman by the name of Terence Biebuyck. But the world of seaside towns is a small one and it didn't take long for this news to reach Gustav. He abandoned his tasks and set out to confront the pair of them. He never made it inside the house. A drunken fight broke out and Gustav was stabbed to death on the doorstep.

Yvonne was now the key witness in the trial of her lover for murdering her husband. Her response was to descend further into alcoholism and a reliance on tranquillisers. The trial made the front pages of the national newspapers, the scandal reverberating through Margate and the tightly knit fairground scene. Yvonne continued to perform at Dreamland during this time but she was frequently incapacitated by drink and her career took a fatal blow when she drunkenly crashed her car one night, breaking both legs and fracturing the base of her spine, the tragedy compounded by a hefty fine and a two-year ban from driving.

In July 1976 Biebuyck was sentenced to three years for the manslaughter of Kokos. Yvonne vowed to wait for him, but her life was crumbling around her and the future looked bleak. Now, pushing 40 – with her husband dead, her lover in prison for his killing, a custody battle for her daughter looming and mounting debts, she could see no way out. And it was at this nadir in her fortunes that Peter Catchpole made one of his timely appearances, with what seemed like the answer to her problems.

He persuaded Yvonne to sell her Wall of Death, with the plan of taking it to Australia, and suggested she accompany him; she could retire from riding the Wall and just do a little light work, selling tickets for the shows. Although reluctant, Yvonne agreed to the proposal – but over the next few months Catchpole witnessed the reality of her decline. The sassy star attraction he had known in Africa had become a desperate figure: a lonely, middle-aged alcoholic, unreliable and erratic. He withdrew the job offer – but now the Dreamland Wall of Death belonged to him. And according to Allan Ford, losing her Wall was the final straw.

On 4 January 1977, Yvonne's body was found in her home. She had lain undiscovered for several days and was slumped in an armchair surrounded by empty drug bottles, her two Chihuahuas prowling around her. In a handwritten note to her imprisoned lover she had written: "I am really no good for you. What a mess I have made of our lives...Please forgive me, I love you. Life is only a means to an end. Up on our star we will be alive and I will see you again one day." Finally her handwriting tailed off, the last words a scrawl: "I can't see the lines on the paper. It's no good Terence." It was a sorry end for the daredevil queen of Dreamland, whose star once burned so brightly.

There is still a generation of Margate residents who remember Yvonne Stagg. But the new breed of Dreamland visitor will be unaware of her role in the town's chequered history; they will come for the vintage funfair, the Turner Gallery and Margate's famous sunsets.

Yvonne's daughter, Minka, now in her late forties, is glad to see the revival of Dreamland; and despite the devastating impact on her childhood, she has come to terms with her mother's life story. When she called me from her home in Southend she was resolutely upbeat about Yvonne's legacy, "I am proud of my mum now," she told me. "I'm pleased that people are still interested after all this time. I look just like her, and I'm a good bike rider. I may even learn to ride the Wall one day, who knows?"

Tracey Emin, and William Turner before her, had been enchanted by the setting sun over Margate's west-facing bay. But Yvonne Stagg flew too close to it. While Margate's 1970s seediness both moulded Emin's life and motivated her to escape, Yvonne was a victim of its charms, trapped by its deadly allure.

Torn between the high-octane thrills of small town celebrity and the pedestrian demands of domesticity, she had been unable to reconcile the two – and crashed to earth.

Author Lois Pryce has written the screenplay for "Dreamland: The Yvonne Stagg Story", which is currently in development

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments