The Little Drummer Girl, episode 3, review: This latest BBC dramatisation of a John le Carre novel is brilliantly done

As with everything else in 'The Little Drummer Girl', the music is judged just right, says Sean O'Grady

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

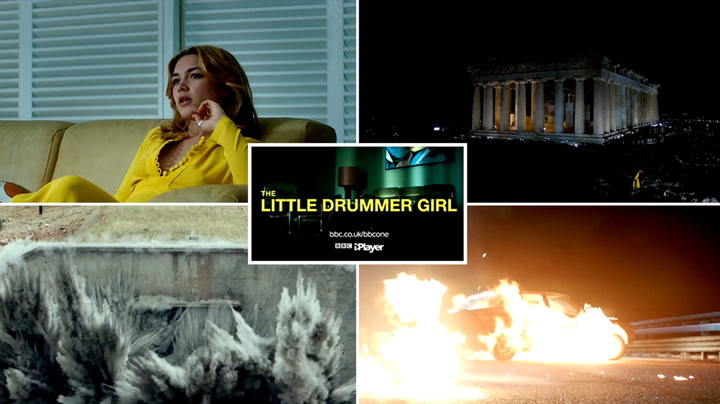

Your support makes all the difference.Well, she made it. Charlie (Florence Pugh), young English actress improbably turned Mossad agent, manages to drive a car full of (concealed) Semtex across Europe without lighting a fag (inadvisable in the circumstances). She has a hairy moment on the Yugoslav-Austrian border (it is set in 1979), when a friendly guard offers her a light, but she makes it to the Austrian town where she dumps it, to be collected by a Palestinian terror gang, watched over by the Israelis. Mission accomplished.

Except, of course, that it is not quite over, for any of the protagonists. For she must now perfect the “part” given to her by the formidably manipulative Israeli spymaster, Martin Kurtz (Michael Shannon, on superb form) – as the lover of a Palestinian terrorist, Salim Al-Khadar. She is engaged in this subterfuge with a handsome Mossad man, Gadi Baecker (Alexander Skarsgard), who is impersonating the Palestinian. But now she must familiarise herself with the real Salim. She has met him once, fleetingly; now she finds him drugged and naked, having been abducted by Kurtz’s team. The Israeli agents catalogue the various scars and birthmarks on Salim’s prone body as if it were a lump of dead meat, which it soon will be. Such details will help corroborate her cover story as she penetrates the terror group.

She finds this, understandably, degrading, for everyone, but her disgust turns to distress when she works out that Salim is not going to be put on trial, but will be executed by the Israelis via extrajudicial methods.

Now Charlie grows more conflicted. Walking through the Munich Olympic Village where, with grim symbolism, Salim is being held, she is learning at first hand the methods and mores of the State of Israel. She chides Gadi for the fate of Salim: “He’s a child”. Gadi, his eyes straight ahead: “He killed a child”. This soldier of Israel is asked, rhetorically, how he can carry the guilt. He frogmarches her to the memorial for the 11 Israeli athletes murdered in cold blood by pro-Palestinian terrorists at the 1972 Games: “We remember”.

And then the line that defines so much of the context: “Your British government promised Palestine to the Arabs and to the Jews. That’s where all this started.” “This” being the ambiguity that helped give rise to the intractable conflict – but also the ambiguities that fill this intricate spy story.

Thus, even this line, delivered by Gadi, echoes ones we heard earlier from Salim when he condemns the British for leaving the Palestinians to the “disaster of 1948”. Not moral equivalence – but a dramatic mirror imaging of the two, Gadi and Salim. It is politically, yes, and – for Charlie – emotional. The feelings she has for Gadi, and, by proxy for Salim, are the psychological source of the hallucination she suffers after her arrival, exhausted, in Austria. When Gadi reads to her the passionate love letters that pass between them, fabricated by Mossad but drawing on their recordings of Salim’s actual words, she is overcome by lust. “Our bodies and our bloods are mixed” – which applies just as well, metaphorically, to the Gadi-Salim relationship. Drunk, exhausted, stressed, bewildered, Charlie drags Gadi onto a bed, but has visions of the Mossad squad standing sentinel around her, Salim on the floor, speaking to her.

Later, back in her bedsit in London, she finds herself weeping over these letters. The scene is intercut with the fake car crash the Israelis concoct to dispose of Salim. The bird’s-eye image of the car scraping along the side of the autobahn are overlaid on to the love letters. Is Charlie crying for Salim, who she has met, whose tragic life story she now knows, and who she has helped to murder? Or over Gadi who has “played” her boyfriend and she is falling in love with? Or both?

This latest BBC dramatisation of a John le Carre novel is brilliantly done. Beyond the obvious, there is one particular reason worth mentioning why The Little Drummer Girl works so well – the music. They’ve paid proper attention to it. From the 1980-vintage Greek disco tunes Charlie hums along to in the car, to the tense title and dreamy incidental arrangements, the music never distracts. As with everything else in The Little Drummer Girl, it is judged just right. The “theatre of the real” as Kurtz calls it, has rarely enjoyed such a fine production.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments