The Crown season five review: This Netflix show is the definition of first world problems

The drama was initially intended as a piece of historical fiction, but the longer it has gone on, the more tawdry it’s become

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Is it possible to square loving The Crown with ambivalence about the “crown”? This has always been the fine line that Netflix’s behemoth has straddled. A fussy, at times unlikeable, protagonist, carrying the flag for institutions that, at the most charitable, represent hereditary privilege, and, at the less forgiving end of the spectrum, the atrocities of the British Empire. As mitigation, the show’s creator Peter Morgan has turned the central figure, Elizabeth II, into a prism through which to view the 20th century. From the twilight of Empire through the Cold War, by way of crises in Suez and Falklands, Aberfan and the Troubles. A noble solution, until, that is, you run out of history.

And so we find ourselves now, with the show’s fifth outing, firmly in the recent memory. John Major is prime minister (played by Jonny Lee Miller, who makes Major look like he could kick the s*** out of you). Prince Charles (Dominic West) is a jug-eared familiar, and Anne (Claudia Harrison) the animate bouffant we all know. The Queen, now played by Imelda Staunton, looks like the Queen from the coins of my childhood. “The clarity of that permanence felt so reassuring,” Philip (Jonathan Pryce) says, of his marriage. Well, if The Crown has been about exploring the backwaters of the Queen’s personal history we have finally arrived at that idea of permanence. Her enduring legacy: mother of the nation.

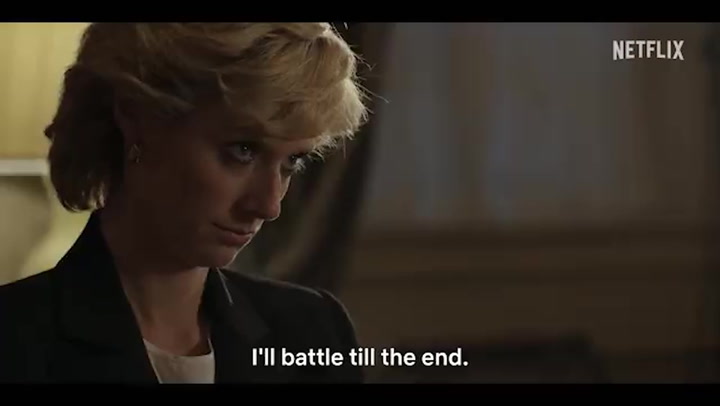

Now the dramatic baton – which began its slow exchange in the fourth season – is handed to the disintegration of Charles’s calamitous marriage to Diana Spencer (Elizabeth Debicki). Debicki is physically unlike the recent iterations of Diana we’ve seen on screen: so willowy that you expect to find her weeping over a village pond, and so tall that viewers will be Googling “Princess Diana REAL height” in their droves. “You can judge the health of a family by the state of the marriages within it,” she tells Major at a Balmoral shindig. “I don’t give any of us more than six months.” Just as the camera loved Princess Di, so too does The Crown seem fascinated by its facsimile. The Queen herself is rather an afterthought here.

At this point it is my sombre duty to impart the news that, since the last season of The Crown aired in 2020, the Queen has died. The temptation towards valediction and memorialising has been avoided, thanks to the production schedule. Instead, the Queen is a trifling and peripheral figure. She petitions for upgrades to the Royal Yacht and avoids Mohamed Al-Fayed (Salim Daw). After the marital tussling or preceding seasons, Elizabeth and Philip have settled into a blandly inspirational form of contented cohabitation. “You make a better person of me,” announces Philip, mawkishly. “And you of me,” replies the Queen. “Aww” or “yawn”?

In fact, that settlement that The Crown made, in order to entice republicans into its portrait of Britain’s first family, seems to have evaporated. In 1992, political scientist Francis Fukuyama published a celebrated book, titled The End of History. Well, The Crown seems to corroborate Fukuyama’s thesis. The geopolitical wranglings of post-war reconstruction and the rise of the Soviet Union have been replaced, in the show’s appointed scope, by trivial gossip. “All-out war,” comes the verdict of hack biographer Andrew Morton (Andrew Steele) on the palace’s rumblings. But compared to the JFK assassination or the space race, it all feels rather… Tatler. A whole episode is dedicated to the potted biography of Al-Fayed (a fascinating story, in its own right) just so that he can introduce Diana to his son, Dodi, in the sponsors’ enclosure at Ascot.

The reality is that The Crown ran out of steam a while ago. It was intended as a piece of historical fiction, playing on the way that the early days of Elizabeth II’s reign had disappeared into the fog of history. The longer it has gone on, the more it has assumed an exhaustive and soap operatic quality – not to mention that, in dedicating now two seasons to doomed lovers Charles and Diana, it has become increasingly tawdry. The cottage industry surrounding the death of Diana seems to be in a process of exponential acceleration. Debicki’s portrait is mildly irritating, as was Emma Corrin’s before her. Indeed, everyone who’s portrayed the “people’s princess” – from Kristen Stewart to Naomi Watts – has struggled to make her likeable. How long can it be before the Diana industrial complex runs its course?

Needless to say, The Crown is not without its triumphs. The production quality is extravagant, the acting largely very good. Staunton and Pryce are capable inheritors of the central roles, while West and the cohort of royal siblings will provide a solid anchor leg to this multi-generational relay. The writing, as ever, is bold and brash, striking big dumb metaphors (“dependable and constant, capable of weathering any storm”, the Queen says of her beloved Royal Yacht. “Sometimes these old things are too costly to keep repairing,” comes Charles’s withering opinion) but remaining the right side of charming.

It’s a shame, then, that The Crown is now so much about the “crown”. Part hagiography (“She never stops, she never complains, she never puts a foot wrong!”), part family psychodrama – this penultimate season feels more insular, more gossipy, than ever. And without the compromise of a grand scope, The Crown is the very definition of first world problems.

The Crown season five streams on Netflix from 9 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments