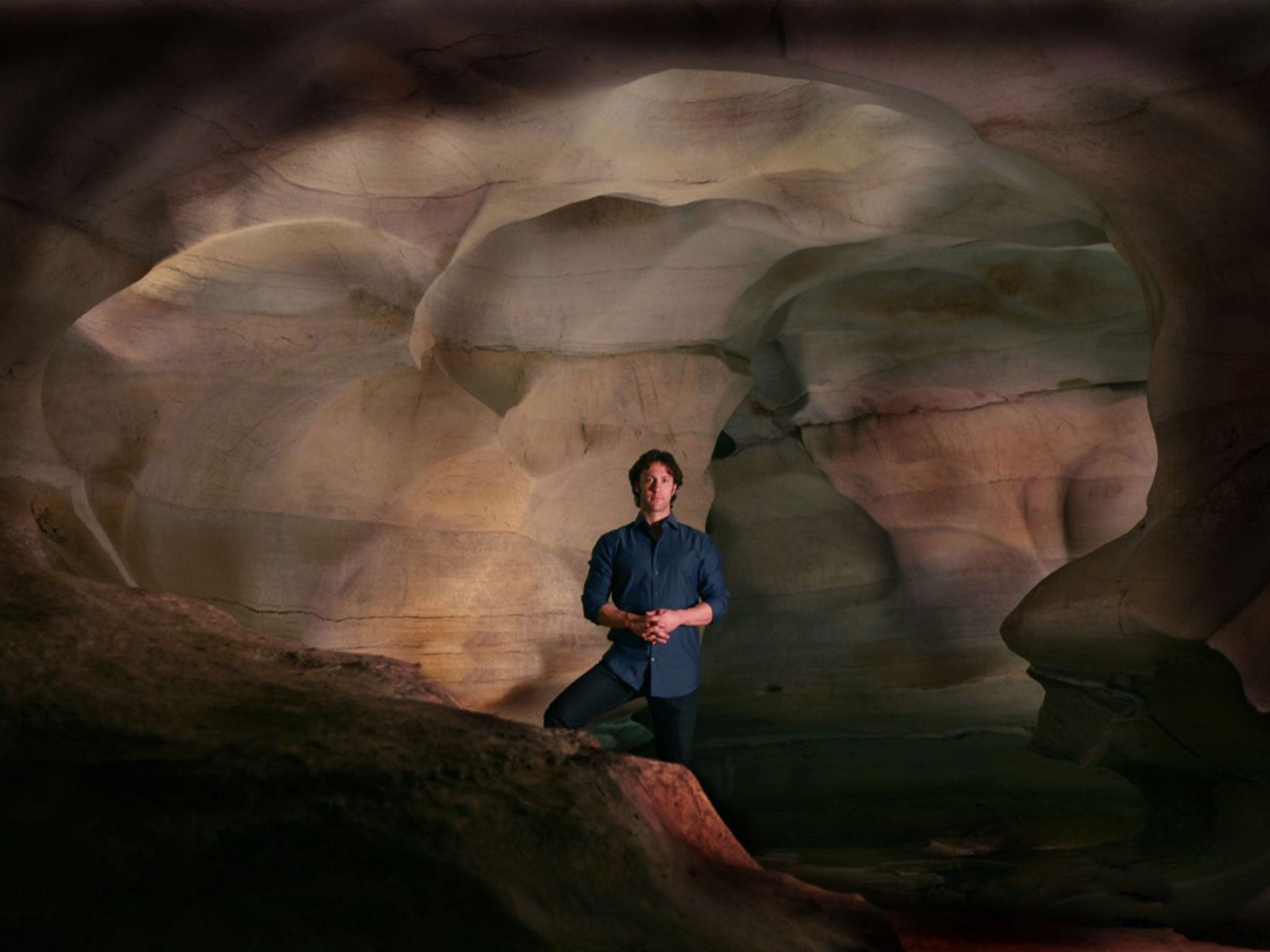

The Brain with David Eagleman, TV review: How we distinguish between Donald Trump and his waxwork

Dr Brian Eagleman took a journey through the three pounds of amazing spongy stuff you have between your ears

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I suppose that questions don't get much more profound than "what is reality?" Anyone who has had the misfortune to study philosophy at university will know the terrible sinking feeling when the lecturer holds a hand up and asks "how do I know this my hand?"

Having watched The Brain, a journey with Dr Brian Eagleman through the three pounds of amazing spongy stuff you have between your ears (if you're lucky), I am now in a slightly better position to answer the question. The answer is: "the thalamus". It's like this, you see. Your eyes get all these visual signals (though we only sense one trillionth of all the light there is out there, that is we miss out on all the ultraviolet and infrared stuff). We then turn those electromagnetic signals, via our eyes, into electro chemical signals in the brain. They then get put through the thalamus, which is a sort of clearing house or CPU for visual stimuli.

At the same time as your eyes are piling images and colours and movements into the thalamus, the visual cortex next door, and your big visual memory/model of the world is also sending images into your thalamus. It is telling your thalamus, based on long experience, what it really ought to be seeing. The thalamus then arbitrates between the two to decide whether you can indeed believe your eyes. Thus it can help you work out if you're face to face with an amazingly realistic waxwork of Donald Trump or the real Trump, say. When the thalamus makes a wrong call then you make a mistake, and you try to shake hands with him. Then you learn not to do that again.

Schizophrenia, for example, is simply a different perception of the world but with distressing and sometimes dangerous consequences. It is essentially an extreme version of when you get fooled by an Escher painting, or you momentarily think your train carriage is moving when in fact it is the train next door that has just set off. Your brain only perceives what it has evolved to perceive, and can get things wrong. If you are a blind person who has just been given eyes and you see the world for the first time, you will fail to recognise the hand you see as yours, or even that it is a "hand".

A little late, and maybe not the answer that would earn me an alpha, but that is what I would say to a philosophy tutor now.

Mockumentaries are also a sort of subversion of reality. The classic Spinal Tap shredded the pretensions and sillinesses of the music world, but with the recent deaths of David Bowie, Glenn Frey and Lemmy I felt a little guilty at enjoying Brian Pern: 45 Years of Prog and Roll. This second episode of six followed this former lead singer of Thotch, naturalistically rendered by Simon Day, into the Hollywood Hall of Fame, and relived his solo success with the 1985 album, Spirit Level.

All the rock celeb clichés are there, including estranged teenage children named Ripple Pegasus Pern and Tallow Agamemnon Pern, but the best line by far was that during his time in Los Angeles the thing Pern most missed about Britain was that he hadn't seen dandruff in six months. Certainly a sort of reality, that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments