Making a Murderer: What to do if Netflix documentary made you really angry

Documentary series prompts fury among viewers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Warning: this article contains spoilers. Finish the series before you read.

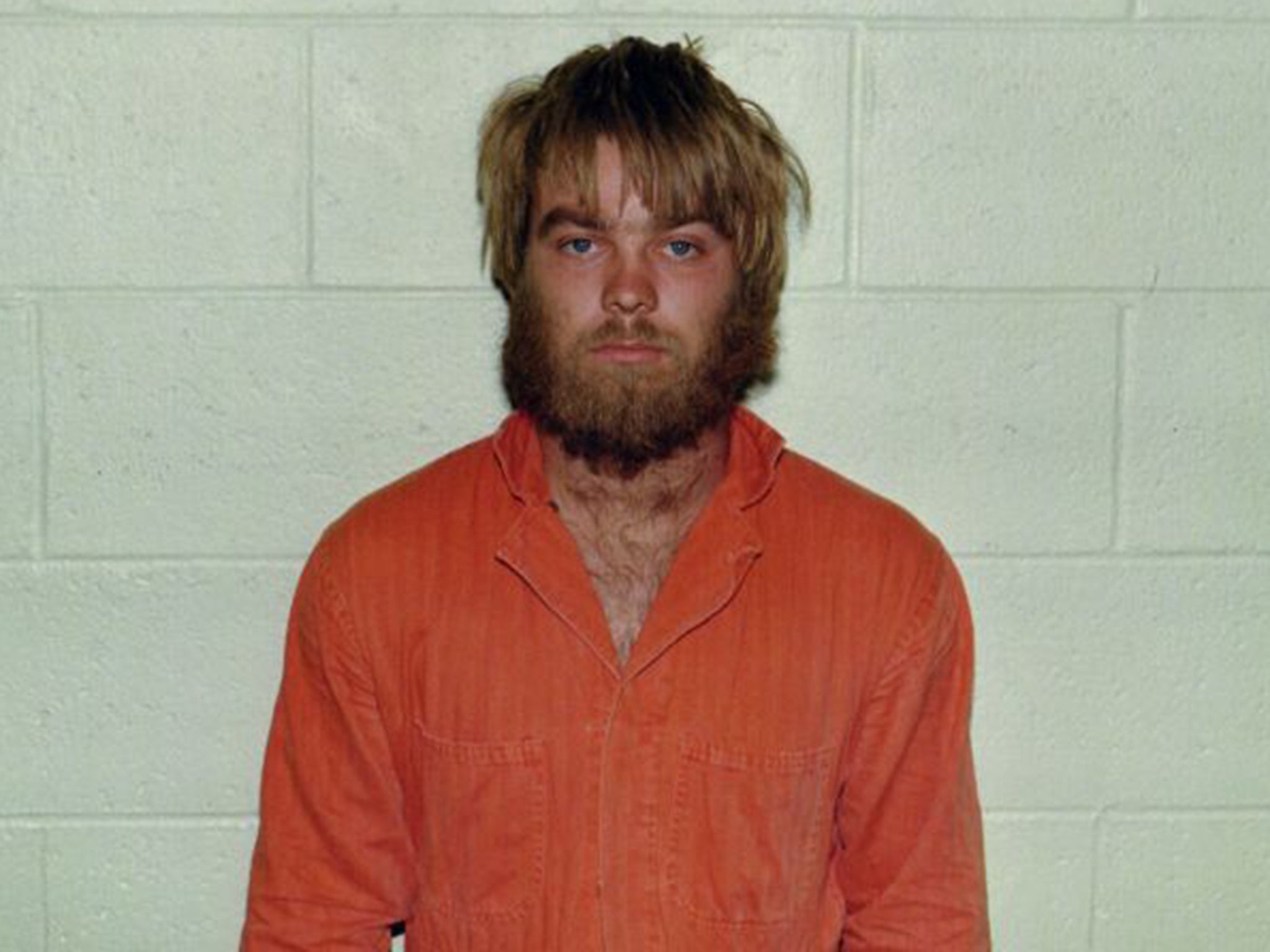

The Netflix documentary series Making a Murderer has people furious. More than 400,000 people have signed a petition demanding Steven Avery’s release from prison, following his conviction for the murder of Teresa Halbach. Anyone who has watched the series has a view on whether this conviction was secured under suspicious circumstances.

Avery originally spent 18 years in prison after being wrongfully convicted of sexual assault in 1985. He was later cleared thanks to developments in DNA science and serious concerns were raised about the police investigation into that case. Avery filed a $36 million lawsuit against local law enforcement in 2003 but was arrested for murder before it could be settled.

Making a Murderer charts the progress of the murder trial, raising questions about evidence being planted and witnesses being coerced into testifying to implicate Avery in the crime.

The filmmakers and the prosecutor in Avery’s case are currently slugging it out in a media slanging match, each side accusing the other of having been selective in their use of evidence.

We know that miscarriages of justice happen. Avery’s own history testifies to that. The Innocence Project has reported that there have been a staggering 337 post-conviction DNA exonerations in the US since 1989. Some of these people served decades in prison. Florida man James Bain, for example, was released from prison in 2009 having served 35 years for a crime DNA now shows he could not have committed.

The bad news for Avery is that in the absence of DNA evidence proving someone else committed the murder, it is immensely difficult to get a conviction overturned when all appeals have been exhausted. Those who believe in Avery’s innocence will be haunted by the scene in the final episode of Making a Murderer, in which his highly competent team of lawyers sits around a table utterly defeated.

The need to balance a fair trial with the need to have some finality to a case means that adversarial criminal justice systems can be reluctant to admit mistakes have been made.

So other than having uncommon powers of patience, resilience and determination what can you do if you think there has been a miscarriage of justice? Here are five courses of action:

1. Turn detective

The easiest way to overturn a conviction is to discover fresh evidence. Appeal courts are very reluctant to overturn a conviction if all the evidence was put before the jury at trial. The rules of criminal procedure aim to create an equality of arms at trial between the prosecution and defence. However, this overlooks the fact that there is a great discrepancy between the two at the investigatory stage.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Prosecution authorities can draw on the significant investigative resources of police departments, which the defence cannot hope to match. At trial, the defence generally seeks to rebut the prosecution’s arguments rather than investigate other possible explanations. It is not the job of the defence team to identify the culprit, they only have to show that there is reasonable doubt about their client’s guilt. But often, the only realistic chance of overturning a conviction comes from discovering some other possible explanation for the crime – such as evidence pointing to someone else’s guilt.

People are often exonerated because of scientific developments – particularly in DNA. This means that, sometimes years later, more can be done with existing DNA evidence than could be done at the time of trial.

Fans of the series will be aware that arguments about ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tests are particularly important in Avery’s case. If EDTA can be proven to be present in the samples of Avery’s blood found in the victim’s vehicle, it would significantly strengthen the defence’s argument that evidence was planted by police as it would show the blood sample had been kept in a test tube. Developments in EDTA testing in Avery’s favour would seem one of the best chances of overturning his conviction.

3. Get a lawyer

There are often problems getting legal advice post-conviction as at this stage the funds have usually dried up and public assistance is usually limited.

If you believe in Avery’s innocence, Making a Murderer ends on a very bleak note. No longer able to afford his legal team, he is left by himself to plough through voluminous quantities of documents in the hope of finding some source of exculpation.

In the US you can write to the Innocence Project, which supports post-conviction clients – and indeed supported Avery in his first case. Its counterpart organisation in the UK, the Innocence Network, has been disbanded. However, there are organisations such as the Centre for Criminal Appeals and Inside Justice which help with post conviction cases, as well as a number of university law schools.

4. Call your celebrity friends

Miscarriage of justice cases need a campaign to keep the issues in the forefront of public consciousness and to further investigations. This requires journalistic, public relations, and campaigning skills that are beyond the remit of most lawyers.

Nothing attracts media attention to your campaign like celebrity endorsement. The case of Kevin Nunn is one such example. Nunn was convicted of murder in the UK in 2005, despite arguing that the police should release forensic samples for re-testing. He didn’t get much media attention until the actor, Tom Conti, offered to pay for the re-testing. Nunn eventually secured a hearing at the British Supreme Court, but his efforts to get forensic samples re-tested continue.

5. Go to the top

Many legal systems allow for some sort of intervention by the executive when there is exceptional concern over a conviction. In Avery’s case it is the Governor of Wisconsin and not the President of the United States who has the power to pardon. That’s because Avery was convicted of state rather than federal crimes.

If you feel Avery should be pardoned you can contact Governor Scott Walker of Wisconsin by emailing him at govgeneral@wisconsin.gov or writing to Office of Governor Scott Walker, 115 East Capitol, Madison, WI 53702.

Richard Owen, Director Essex Law Clinic, School of Law, University of Essex

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments