Twin Peaks at 30: How David Lynch’s terrifying oddity changed television and melted our brains in the process

In 1990, the meticulously weird TV drama was unlike anything people had seen before. Ed Power tracks the journey of ‘Twin Peaks’, from its haphazard beginnings to its triumphant revival

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With weeks of enforced isolation behind us and many more stretching ahead, it’s the perfect moment to reflect on Twin Peaks, which marks its 30th anniversary on Wednesday. The message running like a ghostly thread through David Lynch’s oeuvre is that nothing is as terrifying as life lived day by dreary day. It’s a lesson that resonates more loudly than ever as we reckon with empty streets, creepy calm – and a sense of profound wrongness in the universe.

“It was a slow show, but you never felt it dragged,” observed Caleb Deschanel, the acclaimed cinematographer who directed three episodes of Twin Peaks during its original two-season run from 8 April 1990 to 10 June 1991.

“You always sensed there was something going on under the surface that you had to find. The leisurely pace of it felt like there was a time bomb in a bag in the side of the room. It had this sense that at any moment something terrible could happen.”

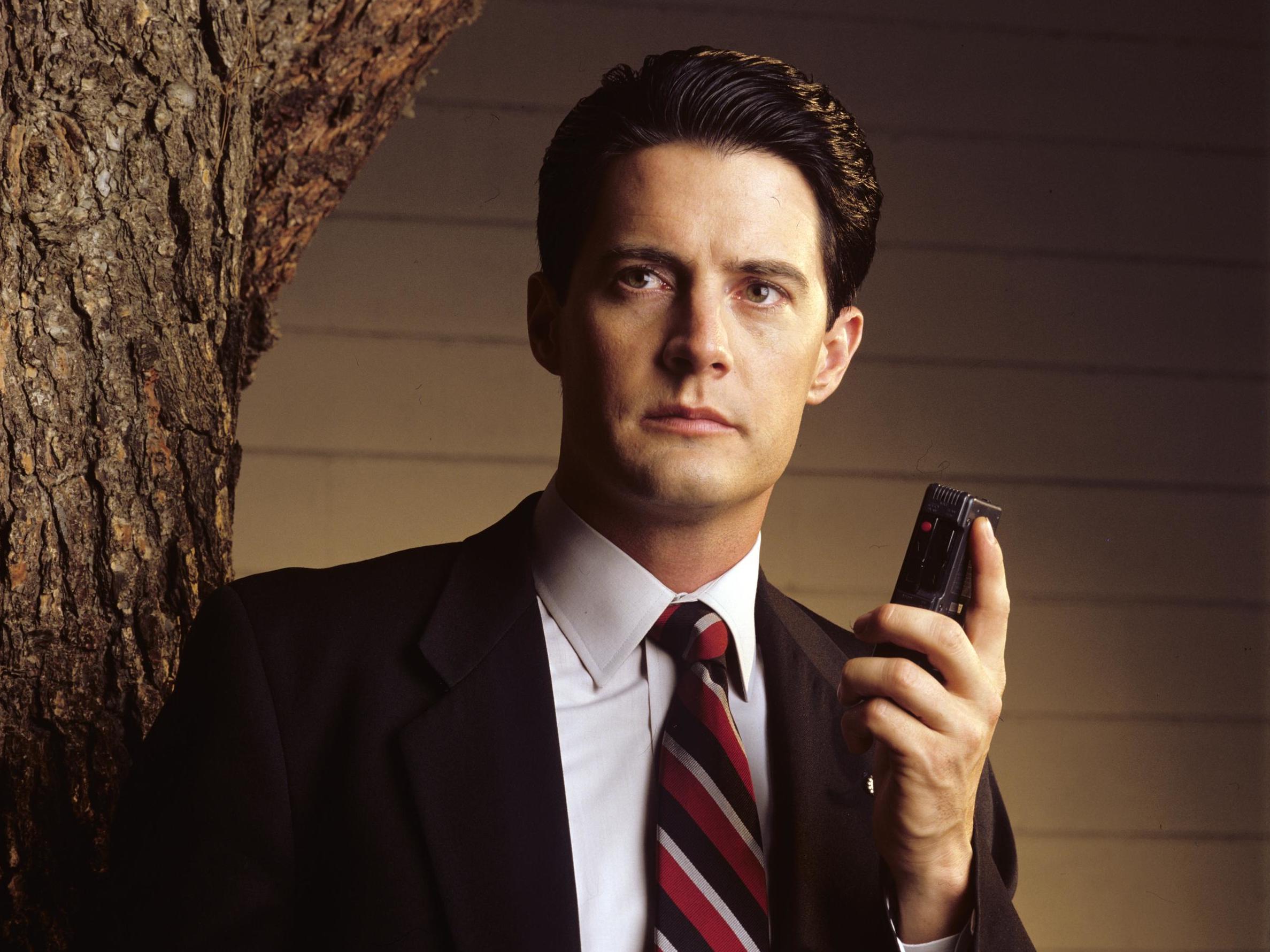

On the outside, Twin Peaks was a conventional murder mystery set in the archetypal small American town. One grey day, the body of a young woman named Laura Palmer is discovered near a riverbank wrapped in plastic. She has been brutally killed and all of Twin Peaks, a logging town in Washington State, is shocked. Enter Kyle MacLachlan’s FBI agent Dale Cooper. He is soon confabbing with dancing dwarves, peeling back the layers on Palmer’s secret life and praising the excellence of the local cherry pie.

As Deschanel said, Twin Peaks always felt as if it was tiptoeing along a precipice. One of Lynch’s great insights is that few things intertwine more easily than evil and everyday life. To this he added lashings of his signature uncanniness. Here is a director who can pour existential dread into something as clichéd as the mid-town Manhattan skyline twinkling at night, as he did when he reconnected with the Dale Cooper extended universe for the first episode of Twin Peaks: The Return in 2017.

Yet he did so while also tapping into a reservoir of nostalgia for better days. Somehow this surrealistic thriller doubled as a big-hearted homage to the America of picket fences, coffee refills and fresh-from-the-oven comfort food. And then he pulled it off all over again with Twin Peaks: The Return – a starrier, bolder, more baffling repackaging of the original’s themes and obsessions. There has never been a more impressive second act in American TV.

Twin Peaks was also partly autobiographical. Lynch, the son of a US Department of Agriculture research scientist, moved around a great deal with his family in childhood. Growing up, he lived at various times in Sandpoint, Idaho; Alexandria, Virginia; and Spokane, Washington, which may have served as his doorway into the Pacific northwest milieu.

In MacLachlan’s Dale Cooper, in particular, it has been theorised that Lynch saw something of himself. Cooper is a straight man in a world teetering on madness. That is how Lynch is often described onset – softly spoken and grounded amid the chaos of a big production working through the gears.

That was the notion floated by his ex-wife Mary Sweeney. And it is borne out by those who worked with him on Twin Peaks and recall his Agent Cooper-esque deportment.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“David is not difficult to work with but he absolutely has to have what he wants. He’s not a rude person or a screamer at all. He’s very much a gentleman, but he has to have what he wants,” set decorator Leslie Morales told Brad Dukes in his book Reflections: An Oral History of Twin Peaks. “The only times I could see him act completely differently was when he was speaking with studio executives about more money or an extra day – he was very different than the David you worked with as a director.”

Twin Peaks is too meticulous to be considered an accident. But its gestation was surprisingly haphazard. In the mid-Eighties, after his Oscar-nominated The Elephant Man (1980) but before the definitive Lynchian document that is Blue Velvet (1986), Lynch had agreed to collaborate with screenwriter Mark Frost on an adaptation of the Marilyn Monroe biography Goddess.

Frost and Lynch were from different universes. The former had cut his teeth on gritty cop show Hill Street Blues, serving as executive story editor from 1982 to 1985. As a screenwriter, he didn’t muck about. His scripts got to the point, and without pretension or affect.

Strangely, however, he and Lynch, the laureate of the discombobulating, hit it off immediately. Goddess would become trapped in development purgatory, with the studio getting cold feet upon learning that the film would imply Bobby Kennedy had arranged for Monroe’s death. Yet Lynch and Frost remained close.

Several years later, when Lynch needed a friend, Frost was there for him. Blue Velvet had been a critical and commercial success. It also foreshadowed Twin Peaks in its negative-image take on the American idyll – Norman Rockwell turned upside down, dragged, wailing and hyperventilating, through the looking glass. And it featured an Agent Cooper-esque performance from a 26-year-old MacLachlan (already a Lynch veteran having starred in his baffling but brilliant 1984 adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune).

Lynch had done weird before, but never so pointedly. In The Elephant Man, Dune and Eraserhead (1977) he had examined freakishness as a doctor might an open wound. With Blue Velvet, he was coming out and saying what he really felt: that we, all of us, were the freaks.

And yet it was then, at the moment of his greatest artistic triumph, that the rug was yanked away. The De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, which held the rights to several of Lynch’s upcoming projects, went bankrupt after a string of flops, among them 1986’s King Kong Lives and the 1987 Kathryn Bigelow vampire thriller, Near Dark. All of Lynch’s plans were flushed away with it. These included One Saliva Bubble, a conspiracy comedy that would have starred Steve Martin and Martin Short and been set in small-town Kansas.

“We had all our scouts, had it cast, was right there ready to go,” Lynch said in 1990. “Dino [De Laurentiis] kept delaying it, delaying it, delaying it. It became obvious it wasn’t going to happen: There wasn’t any money. Shortly thereafter, his company went bankrupt. We saw the writing on the wall.”

So Lynch, then aged 44, had to start over. As it happened, his agent had been pushing him to consider working in television and suggested Frost as a potential collaborator. With nothing to lose – he had lost so much already – Lynch agreed to take a meeting.

Over coffee, possibly pie (the records are vague), he and Frost brainstormed. Their ideas were gleeful and bonkers – and utterly removed from the picket-fence environment Lynch had invented with Twin Peaks. The Lemurians was about a lost race of subterranean beings trying to take over the world, with only the FBI to stop them. Lynch and Frost were offered a movie deal. Lynch felt it should be a series.

Then came the lunch date that would change everything. Lynch met his agent, Tony Krantz, at Nibblers, a restaurant on Wiltshire Boulevard in Los Angeles (“It’s like a time warp,” went a recent Yelp review. “It’s classic, but in that tacky carpet, orange upholstery, senior special kind of way”). Krantz had a suggestion: rather than sci-fi, Lynch should drill deeper into the themes explored in Blue Velvet. At one point, the agent gestured to the diners, drinking their coffee and tucking into their pie. “You should do a show about these people, the customers here in Nibblers… A show about real life in America – your vision of America, the same way you demonstrated it in Blue Velvet.”

Lynch and Frost gave the project the working title “Northwest Passage”. The murder-mystery component was hatched by the duo at another favourite hang-out. “We were at Du Par’s, the coffee shop at the corner of Laurel Canyon and Ventura,” the director would remember. “All of a sudden Mark and I had this image of a woman’s body wrapped in plastic washing up on the shore of a lake.”

Frost had a holiday home at Sand Lake in upstate New York. He recalled the story of a murdered girl and how her death in 1908 had opened a rift into a place of unimaginable darkness in the community. “There was supposedly a ghost in the area of this crime that some people said they had occasionally seen. I went down to the city hall and did some digging and found that a murder had taken place there, in either the 1900s or the 1910s. I believe the girl’s name was Hazel Grey.”

“They talked about a real sense of mood of this town in the northwest where everything was pristine and beautiful but that behind the curtains was a world with the lives of people that were quite opposite of the environment that they lived in,” Chad Hoffman, vice president of drama at the ABC network, told Dukes. “It was all about secrets and I remember David and Mark talking about what you see in the foreground is not what’s going on in the background.”

They were off to the races. It was decided to film on location in Snoqualmie, population 10,000 and 28 miles east of Seattle. MacLachlan, a Washington native who had attended university in the city, was delighted to go home. Also from the area was Sheryl Lee, a newcomer with modest acting experience whom Lynch cast on the spot, so convinced was he that she was meant to play Laura Palmer.

“When you work with David Lynch, you have to accept that you’re working with the unknown,” Lee told a fan convention in Australia in 2018. “It’s all about being in the present. A logical approach, you know, ‘What’s my motivation? What does this mean? Why am I saying this?’ that’s never going to work. For me, I need to trust and surrender. By being present like that, you open up and you can access this bigger force.”

However, it was with the music that Twin Peaks truly became Twin Peaks. Lynch was close to composer Angelo Badalamenti, who wrote the score for Blue Velvet. In New York, they often hung out together. Recalling the creation of the Laura Palmer theme, Badalamenti described Lynch painting a picture for him – and the haunting progression of piano notes that flowed from the conversation.

“Just slow things down and it becomes more beautiful,” Lynch said to Badalamenti. He instructed the composer to imagine a young woman, clearly upset, emerging from the treeline. She gets closer and closer and the music swells towards a catharsis. Twenty minutes later the piece was complete. “Don’t change a single note,” said Lynch. “I see Twin Peaks.”

“If the show was a boat moving along, Angelo’s music was the river that carried it,” Frost reflected. “It helped create and support the mood of the show. It gave you a very specific sense of time and place that felt outside of real time and real place. It helped elevate the show into a mythological realm that really separated it from the usual TV view of what the world is. I can’t imagine the show without the music. Angelo is such a fun guy and so great to work with, he’s just as important in the Twin Peaks tapestry as anybody else’s contribution and you know, that turned out pretty well.”

The music had come together in a flash of haunting serendipity. So, too, did many of Twin Peaks’s most iconic moments. The demonic figure of BOB was an impromptu creation of Lynch. He was struck by the menacing figure set decorator Frank Silva presented when the camera accidentally caught him glaring into Laura Palmer’s bedroom mirror.

“The shot we were getting ready to do was Laura’s mother’s POV of her daughter’s room after wanting her to come down to breakfast. So, the camera was in the doorway, David was out in the hall, where the ceiling fan is. I was tweaking the bedroom set, getting everything ready to go, making sure everything is in it’s place,” Silva said.

“David jokingly said, ‘Frank, you better get out of there, you’re going to get caught in the camera’. And then suddenly he said, ‘Wait a minute!! Frank, get down to the base of the bed, crouch down, look through those wrought iron bars, and act scared!’ And then they shot the POV, with me at the base of the bed. And it just sort of snowballed from there.”

Later, a fluorescent light flickers as Agent Cooper is examining Palmer’s body. Lynch decided to leave this in, presumably on the grounds that it ratcheted up the sense of the uncanny. Flickering electricity would become a recurring visual tic. Lynch never explained why, although it has been interpreted as a commentary upon duality, and how light and dark, good and evil can exist in uneasy proximity. Maybe he just liked how it came over onscreen.

With a budget of $1.8m, and a cast comprised largely of unknowns or character actors who had seen better days, a pilot was shot in Washington. Waiting to watch it in LA were executives from ABC. Under new boss Bob Iger, the network had been eager to move away from the family friendly image it had cultivated in the Eighties with fare such as The Cosby Show and Family Ties.

This strategy had already yielded two critical hits in China Beach and Thirtysomething (as well as the less successful Cop Rock, a “police procedural musical” with songs by Randy Newman). And it was out of a wish to be taken seriously that the studio had decided to work with Lynch. However, a series of test screenings, for both executives and the public, did not exactly set the room on fire.

“They seemed to like the idea,” Lynch said. “Behind the scenes I think they were nervous and asking questions to people – is this a good idea? I know after we shot the pilot they did a lot of testing. It didn’t go horribly, the testing. But it didn’t go great either.

“I can’t confirm this,” producer Harley Peyton told Brad Dukes in his oral history. “I did hear that when they screened it for the network brass in New York, I guess an old pro, one of the top corporate guys said, ‘This is not going to ever appear on ABC. This is garbage. This is horrible. This will never happen’.”

But it did happen. With the pilot in the can and the series proper shooting, ABCs marketing department sent out video cassettes to every journalist in their contacts list, including the editors of inflight magazines and local papers. The idea was to give Twin Peaks enough hype to overcome its obvious weirdness (we’re not an hour in and Agent Cooper is already talking to a woman cradling a pet log).

In the short term, the campaign worked. Twin Peaks manifested on 8 April in a blitz of buzz. Reviews were kind, too. “Twin Peaks is like nothing you’ve seen in prime time – or on God’s Earth,” said Time. “It may be the most hauntingly original work ever done for American TV.”

“Will it be all things to all people?,” said the Washington Post. “Certainly not. But for the adventurous explorer in the normally tame wilds of television, Twin Peaks is just this side of a godsend.”

Week by week, though, the innately Lynchian nature of the endeavour became hugely off-putting to mainstream audiences. Ratings fell off a log: by the season finale, Twin Peaks was drawing just 17 per cent of the prime-time audience. Still, ABC, mindful of the critical acclaim and of the show’s younger-skewing viewership, renewed it for a second run.

Lynch’s enthusiasm was wilting along with that of the public, however. One potential reason was that his movie career was suddenly on an upward trajectory again. By the time season two came around, he was having success with Laura Dern and Nicolas Cage in Wild at Heart. It was while he was otherwise occupied – though he still occasionally swung by to play FBI agent Gordon Cole – that Laura Palmer’s killer was revealed one-third of the way through season two.

The murderer was her own father Leland. He had done so while possessed by the demonic BOB. “I suppose you wanna asks him some questions,” says BOB as Leland. “Did you kill Laura Palmer?” asks Cooper. “Oooooh…oooooh….ooooh,” shrieks BOB/Leland. “That’s a yes.”

With that, Twin Peaks seemed to shoot its bolt. Those few viewers who had tarried to discover the identity of the killer exited. A new storyline focused on the rivalry between Cooper and former FBI mentor Windom Earle (Kenneth Welsh). “His mind is like a diamond: cold, hard and brilliant,” said Cooper of his nemesis. Nobody cared, Lynch least of all.

And then: a devastating last twist as Lynch rode in to direct the finale. It would prove one of the most unsettling 50 minutes of TV ever aired. Lynch threw out much of the existing script by Mark Frost, Harley Peyton and Robert Engels. But he did retain their original plan to send Agent Cooper once more into the Red Room of the supernatural Black Lodge and into Twin Peaks’s heart of darkness.

As soon as Lynch returned to set, he made his presence felt. Welsh, aka Windom Earle, recalled the film-maker stepping over and immediately taking issue with how the character was being portrayed.

“I was wearing this peculiar outfit that was some kind of plaid jacket with a strange tie,” he said. “David walked over, stops and says, ‘That’s wrong’. I can’t remember if it was the director but whoever was with me said, ‘What do you mean?’ David says. ‘No, no. Windom wouldn’t look like that’. They asked what he should be wearing and he goes, ‘Like an FBI suit that’s all covered in soot and all ripped and torn. Worn out. He’s been sleeping in the bushes”. That was the first time I ever met him.”

“When it came to the Red Room, it was, in my opinion, completely and totally wrong,” Lynch would say of the original script. “Completely and totally wrong. And so I changed that part. A lot of the other parts were things that had been started and were on a certain route, so they had to continue. But you can still direct them in a certain way.”

In the Red Room, an extra dimensional place of “pure evil”, Cooper is confronted by Laura Palmer. She says she will see him again “in 25 years”. Much craziness ensues – including a shrieking Palmer doppelganger and an appearance by Windom Earle. The episode concludes with Cooper, possessed by BOB, grinning and shrieking into a mirror – “how’s Annie… how’s Annie” – in reference to Cooper’s love interest Annie Blackburn (Heather Graham).

Which is where we leave him until Lynch took up the story with the 1992 prequel movie, Fire Walk with Me. A box office disappointment, Fire Walk was, if possible, even more hallucinogenic than Twin Peaks. Among other chills, it featured the most unnerving David Bowie cameo – as missing FBI agent Phillip Jeffries – this side of the Dancing in the Street video. And, 25 years after that, out slithered Twin Peaks: The Return.

But what ultimately was it all about? The enduring nature of evil? The sinful secrets of small-town life? The cosmic transcendence of a good slice of pie? Perhaps all of the above. Maybe none at all. One thing that is for sure is that there’s little point trying to get the truth from Lynch. He isn’t telling and probably never will.

“When you finish anything, people want you to then talk about it. And I think it’s almost like a crime,” he once explained, when invited to unpack Twin Peaks. “A film or a painting – each thing is its own sort of language and it’s not right to try to say the same thing in words. The words are not there. The language of film, cinema, is the language it was put into, and the English language – it’s not going to translate. It’s going to lose.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments