The Sopranos at 20: Creator David Chase reflects on the ending, James Gandolfini and Trump

As the classic HBO series turns 20, David Chase reflects on its legacy and reveals what Tony Soprano would have made of Donald Trump. Interview by Jeremy Egner

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Remember when’ is the lowest form of conversation,” Tony Soprano once told his mob cohorts in The Sopranos.

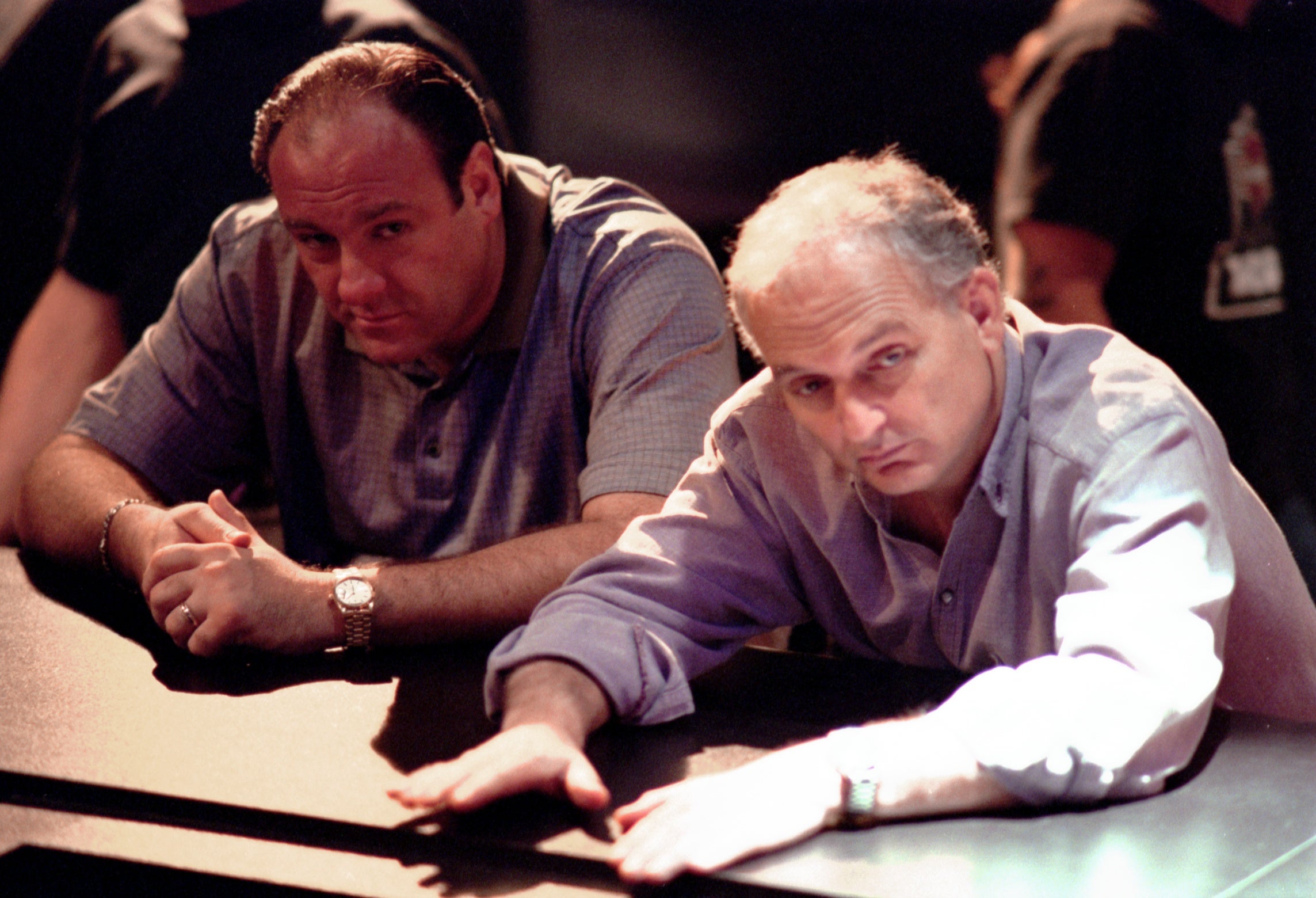

If David Chase, Tony’s creator, doesn’t totally agree with that assessment — “It was a friend of mine in high school who said that,” he said — that doesn’t mean he’s particularly fond of nostalgic reminiscence.

“It’s a cheap thing. It drives me crazy,” he said last week. “I thought revisiting the show would be more pleasurable, but it turns out I’ve forgotten a lot more than I thought I would.”

Alas, it’s unavoidable this month. Thursday (10 January) is the 20th anniversary of the premiere of The Sopranos on HBO, a moment that, as much as anything, signalled the beginning of TV’s still-flourishing era of ambitious storytelling and artistic credibility.

An immediate sensation — in 1999 The New York Times said “it just may be the greatest work of American popular culture of the last quarter century” — The Sopranos demonstrated that viewers would embrace unconventional TV shows, setting the table for what has become known as “prestige TV.”

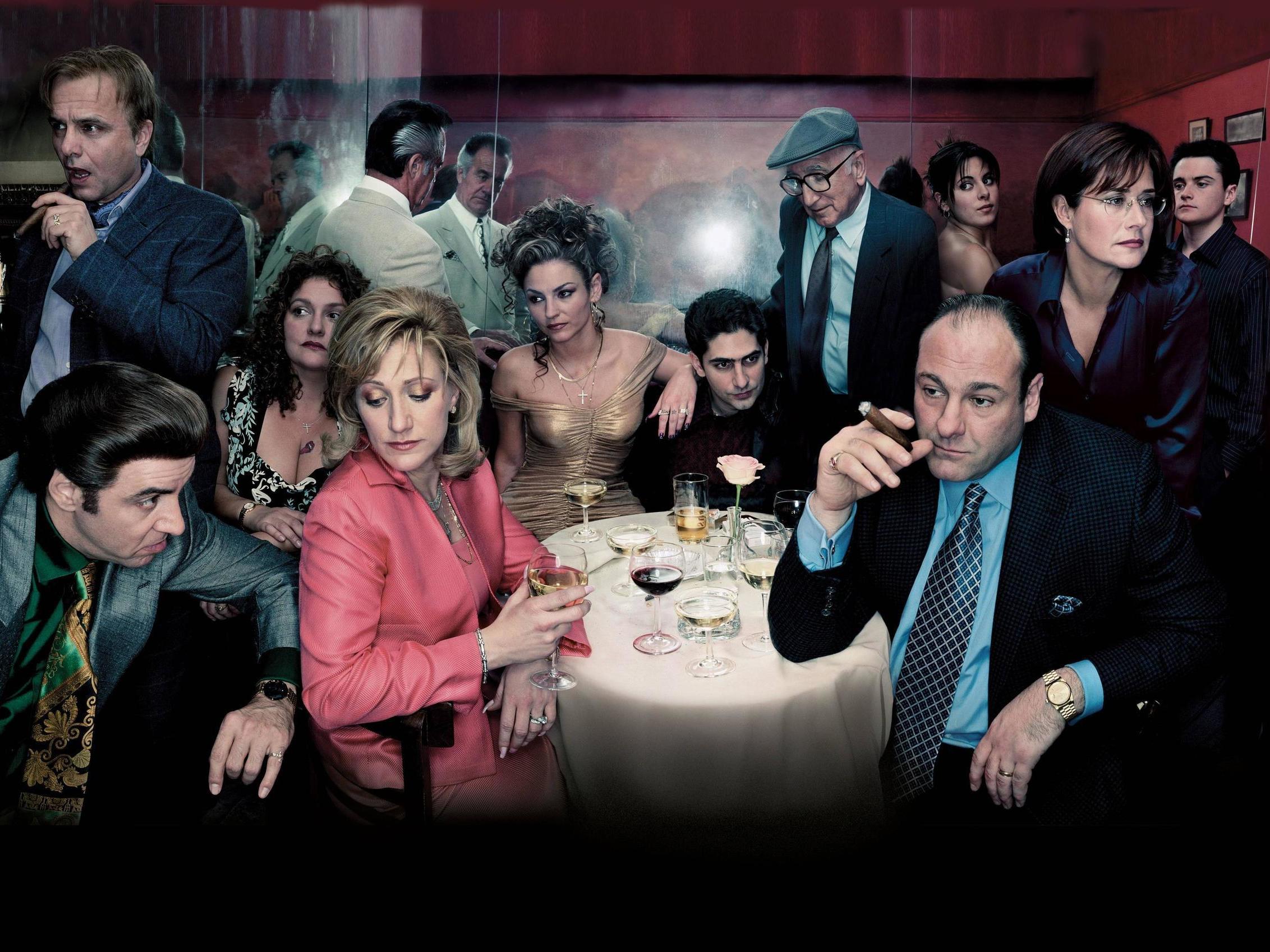

There had been complex, challenging series before it, like Twin Peaks, The X-Files and NYPD Blue. But over six seasons on HBO, Chase’s offbeat story of the depressed, violent but oddly sympathetic mob boss Tony Soprano, played by James Gandolfini (who died in 2013), dramatically expanded the parameters of series television, enlacing its sometimes shockingly brutal mob tale with slapstick comedy, surrealist dream logic and narrative invention.

Phrases like “the Russian in the woods” and “the cut to black” became a kind of pop-cultural shorthand for an uncompromising, auteurist approach to TV making that has informed not just other antihero stories like Breaking Bad or The Shield, but also a diverse array of singular series like Mad Men, Transparent and Atlanta.

“I didn’t think that The Sopranos would chart any kind of new course,” Chase said. “All I wanted to do is just get as close to cinema as I could.”

In the time since The Sopranos cut to black in 2007, Chase made the period rock ‘n’ roll film Not Fade Away and wrote other shows and films that have yet to see the light of day. After years of resisting mob-show pitches, he is now working on a Sopranos prequel feature film called The Many Saints of Newark, which will be set in the title city in the 1960s and involve the father of Christopher Moltisanti (the Sopranos character played by Michael Imperioli). It will likely come out in 2020, Chase said.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Sitting in his Upper East Side apartment a few feet from his writing desk, Chase was terse but thoughtful and accommodating as he looked back on The Sopranos, his gruff demeanor spiked with dry wit. In edited excerpts, he discussed the legacy of The Sopranos, how AJ (Robert Iler) might fit within the Trump White House and, yes, the endlessly dissected finale.

Q: The Sopranos was originally conceived as a film, right?

A: Yeah. I planned to have Robert De Niro as, well he didn’t have a name, and Anne Bancroft as his mother. But I was signing with a new agency and they said mob comedies were dead, so I should forget about that. As it turned out, they had missed their mark.

Q: You’ve talked about how your mother and your relationship with her inspired certainly the early part of The Sopranos. But what were some of the other ingredients?

A: When the show first hit the air, I really overdid it in the press about my childhood. I said I was always depressed and this and that, because I wanted to sell the idea of Tony and depression. Actually, my mother was pretty crazy. But I had a wonderful childhood in many ways. I was really cared for. I was ranging all over the place in this apartment complex that we lived in, just discovering everything. I had good friends.

Q: How much of that found its way into the show?

A: One thing that did was this attraction to nature. The bear. The woods.

Q: Ducks.

A: The ducks. Because even in Clifton, New Jersey, there was a lot of wildlife around then. There isn’t very much anymore. The film I always mention, that informed what I was trying to do, is Saps at Sea, a Laurel and Hardy thing.

Q: Why did you want to do a mob show, specifically?

A: I was Italian-American, and I wanted to see Italian-Americans portrayed. Now these people would say, “You didn’t portray Italians as they are. All Italians are not gangsters.” That was true for the show, too. Dr Melfi [Lorraine Bracco] wasn’t a gangster. Other people they ran into were not gangsters. But the main characters were.

Q: How did James Gandolfini shape Tony in ways that you perhaps did not anticipate?

A: The first day we were shooting, there was a scene in which Christopher told Tony that he was going to write a movie script and go to Hollywood. And in the dialogue, Tony said, “What are you, crazy?” and he gives him a love tap. That’s what I pictured.

And we came to do it, and Jim pulled him out of his chair, shook him by the collar and was like “Are you [expletive] crazy?” And I thought: That’s Tony Soprano. He just felt like a real gangster.

Q: You worked in traditional broadcast television for decades, on shows like The Rockford Files and Northern Exposure. What specific TV conventions were you trying to break out of with The Sopranos?

A: Really all of them. I hated commercials and the way they interrupted everything. I wanted to slow the pace of the episode down or speed it up, as we wanted to. Language. I wanted to create characters that felt like real people and behave the way people behave, which I didn’t see on network television.

Q: How did you go about it?

A: I always had this saying: the first 10 ideas you get, throw them away. And that’s what we used to do, is to just keep going until it was something you hadn’t seen before or couldn’t anticipate.

Q: The show became famous both for surprising resolutions — like when Janice Soprano [Aida Turturro] killed Richie Aprile [David Proval] in Season 2 — and things left unresolved, like the infamous Russian in the woods in the “Pine Barrens” episode. What did those kinds of swerves bring to the story?

A: My wife’s grandfather was from France and he fought in World War I — he was gassed in the war. He had two sons, and when the war was over he came to the United States because he didn’t want them to be around war, and he didn’t want them to go into the army. And then they both went into the Army here in the United States.

I thought about that all the time and I think that’s what life is like. You prepare and prepare for things. “I am going to take charge of something. I’m going to avoid all that.” And it comes from some other side — you never see it. That’s a lifelike thing, and that’s what we were trying to do.

Q: Was there an early moment or episode when you had a breakthrough?

A: I think “College” broke through something for me, the fifth episode of the first season. When Tony took his daughter on a college tour [and brutally killed a former mobster turned snitch along the way]. Some of the best episodes were ones where he was out of his element, or someone was out of their element. “Pine Barrens.” They were like little movies, which is what I was always trying to do: a little movie every week. I wasn’t fond of the idea of doing continuing stories.

Q: Why not?

A: I don’t know. I thought about “Dallas” — I didn’t want to do that. But I let myself be convinced to do them and it turned out to be a really good idea.

Q: Were there any episodes you wish you could do over?

A: The show when they went to Italy. That really wasn’t our element. We really didn’t know what we were talking about, so I didn’t like it as much.

Q: What about the maligned episode about the Columbus Day Parade protest?

A: I don’t regret it, because I had so much vitriol piled up inside me that I didn’t care whether people liked it or not. I know everybody hates it. [Laughs.]

Q: As an Italian-American yourself, were you hurt by the criticism of the show’s depictions of Italian-Americans?

A: No, I wasn’t. It just got me lathered up, that’s all. In “The Sopranos” there were a lot of things that weren’t found in other mob presentations, and it pissed me off that people were kind of blind to that.

We were supposed to shoot “Pine Barrens” in South Mountain Reservation in New Jersey, and an Essex County executive kicked us out because we were such a lousy example of Italians. Then later he went to prison. [Laughs.]

Q: Did you know from the beginning that the show would incorporate more impressionistic elements, like the dream sequences? Things like the Big Pussy fish dream or the Kevin Finnerty alt-reality arc in Season 6?

A: A lot of people hated those dream sequences. There were people who just wanted a mob show, and their motto was “less yakking, more whacking.” And when I would read things like that, it would only make me do more yakking. Look, the show was about psychiatry, and dreams are part of psychiatry.

Q: Edie Falco jokes about wanting to bring the show back, with Carmela as the boss of the family. Has anyone ever seriously tried to get you to resurrect it in some form?

A: No. People approached me about doing more mob stuff, but not The Sopranos.

Q: Really? I would have guessed Netflix would have backed up the Brink’s truck and said, “How much will it take?”

A: Nope. Never happened.

Q: What would it take?

A: To bring it back? I wouldn’t do it. At the end, we were done. I was done.

Q: I recall from interviews from then that Gandolfini was pretty done, too.

A: Oh yeah, he was really done. He was done with me.

Q: He starred in Not Fade Away later, though. Did you guys get along, in general?

A: We got along, but toward the end of The Sopranos he was tired of it and he was tired of me. And I was tired of his foibles. That’s all.

He used to call me a vampire. Then he started calling all the writers vampires, because we used to take the real lives of the cast and put it in the show. Like Tony Sirico was germophobic, so we gave that to Paulie.

Q: We talked about dreams earlier. Do you ever dream about The Sopranos?

A: No, I dream about Jim Gandolfini. I really don’t remember them that well and I never analysed them. Maybe he is Tony Soprano in some of them. He’s angry in a lot of them. [Laughs.]

Q: What do you think The Sopranos did that television hasn’t done before?

A: [Long pause.] I think The Sopranos showed humans more as humans than what had come before it. I mean, on network television those are human beings, certainly. But I think more people could feel like “Tony Soprano is more like me than a doctor, or a cop, or a judge.”

Q: Since The Sopranos, TV has become perhaps the most creatively fertile and ambitious pop-culture medium. Do you take any satisfaction from the fact that you were one of the architects of that?

A: If you say so. But yeah, I take satisfaction that I had some effect on the way things changed. I did want to change things. There is an Elvis Costello song where he says, “I want to bite the hand that feeds me; I want to bite that hand so badly.” That’s the way I always felt about working at the networks, and I think I did it.

Q: What Sopranos influences do you see when you watch television?

A: The use of a deeply flawed hero and his problems. And when news shows talk about Trump, for example, they’ll say it’s like The Sopranos. People use The Sopranos as an example of crookedness and culpability.

I don’t watch a lot of series television. Unfortunately what I do is spend my time watching CNN, Fox and MSNBC. So I get good and depressed, and angry.

Q: I’d forgotten, until I rewatched it recently, that in the finale AJ talks about wanting to work as a helicopter pilot for Trump. Had that worked out, he might be part of the administration now.

A: He might be the new chief of staff. He’d be buddy-buddy with Stephen Miller, I know that.

Q: What do you think Tony would have made of Trump becoming president?

A: He would think the guy was full of s**t. Whether he thought he was a good president or not — I don’t know that Tony thought much about that question at all, with anybody who was in office. But I know Tony would have thought Trump was penny-ante, in terms of his lying and presentation.

Q: Of course, the finale is best remembered for the cut to black and all the commentary that followed. Would you have done anything differently had you known you’d get asked about it for years?

A: I don’t think so. You couldn’t help but be surprised — beyond surprised — at the response. It was a pleasurable sensation that people were talking about it, that it made an impression on people. It made a lot of people angry. Sometimes I couldn’t believe it was that important to people.

Q: With the 20th anniversary coming, are you ready for another round of “Is Tony dead or not?”

A: I’ve got to say I’m just bored with it. I also feel like, Jesus, there were 86 episodes and you’re fixated on that? Can’t we talk about something else?

Q: You did an interview with the Directors Guild of America in 2015 that extensively broke down the final sequence. Was that an attempt to just put the whole thing to bed?

A: Might have been. I really don’t recall my reasons. I was trying to provide a context.

Q: Is it frustrating that even after that, many people don’t seem to want to take you at your word?

A: It’s frustrating. It makes me use bad words. But it’s not surprising, you know? And I don’t have any statistics to prove it, but I think it’s become more accepted as time has gone on.

Q: I think the point isn’t whether or not Tony was killed. It’s the uncertainty that’s the point, and the way the scene’s crazy tension makes us aware of the passage of time and how choices shape the brief bit of life we get. Most people can’t control when or how they die, but the choices are ours. Is that totally off base?

A: No, that’s not off base at all.

Q: I think there’s some hope in it.

A: You’re the first person who’s said that. There is some hope in it. “Don’t Stop Believin’” is the name of the song, for Christ’s sake. I mean, what else can you say?

Q: Is there a correct answer to the question of whether Tony is alive or dead?

A: I don’t think so. I don’t think so.

© 2018 The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments