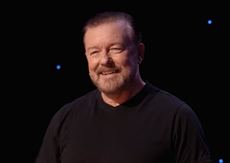

Stephen Merchant: ‘Ricky Gervais is braver than I am... he’s quite happy to give the finger to the world’

The co-creator of ‘The Office’ and ‘Extras’ talks to Adam White about series two of his BBC One crime-comedy ‘The Outlaws’, people assuming he is his comedy persona, and how ‘the left’ has taken over from Mary Whitehouse

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For a few hours in the summer of 2020, everyone decided that Stephen Merchant was feuding with Ricky Gervais. The pair were once professionally inseparable, twinned masters of cringe comedy and tales of existential pique. But it’d been a few years since they’d written The Office, Extras and Life’s Too Short together, and a divorce seemed to have taken place. Merchant had gone to America, popping up in some expected places (his fish-out-of-water star vehicle Hello Ladies) as well as some slightly jarring ones (his role as an albino mutant in X-Men sequel Logan). Gervais, meanwhile, seemed to have found a home in the middle of Twitter’s daily culture wars, alongside being the creator and star of After Life, a polarising comedy-drama about a man grieving his late wife. So when Merchant tweeted that his least favourite bit of storytelling shorthand is a character “watching old home movies of dead child/wife” to signal an inability to move on… well, assumptions were made.

“Whenever people stop working as closely together as they were, people immediately assume it’s ‘knives out’,” a slightly exasperated Merchant explains over Zoom, his head in a black cap and his arms like a spider plant. He and Gervais aren’t estranged, he says, and the tweet had been misconstrued. He hadn’t even seen After Life, let alone chosen to send a bitchy subtweet about his old writing partner. “Why would I? It was such a strange idea to me, that I’d take a swipe at Ricky by doing a tweet, and [make] an abstract criticism of his show.” He sighs.

Merchant and Gervais can’t help but be paired in the public consciousness. Beyond their genre-defining work together, they share a comic rhythm – an awkward-male deadpan that can be both wildly inappropriate and perpetually downtrodden. As writers, they gravitate towards the sentimental; emotive mush smuggled in beneath the knob jokes. As public figures, however, they’re today perceived very differently: Gervais a self-mythologising warrior against “wokeness”, Merchant his quieter Noughties sidekick. Or the awkward one with the thick Bristolian accent and spectacles. And maybe, just to further this most biased of readings, the true brains of the operation. As evidenced by that 2020 Twitter snafu, we tend to project onto them our own world-views and assume – or hope – that they’ll mirror them back to us.

But, as Merchant makes clear in conversation, few of us truly know him, or his thoughts on the world. There’s the Merchant we see on television and in stand-up – gawky, boisterous, always flirting with skin-crawling overcompensation – and the private Merchant, who has long wrestled with the less nuanced ideas people have of him. “I’ve used that shtick as comedy fuel, because I find it funny,” the 47-year-old says. “But the danger with that is people assume that’s the real you. There’s a portion of people who take me at face value and think that I’m always the putz, or that the Bristol accent makes me kind of parochial. [Or] that I’m just that tall, gangly guy who’s sometimes amusing on Graham Norton.”

Merchant is at home in Los Angeles and appropriately sat in a sterile office, surrounded by white walls, with his blinds closed. Shadows of palm trees can just about be glimpsed through them. We’re here to talk about The Outlaws, a crime comedy he stars in and co-writes that’s returning to BBC One this week. It’s an enjoyably odd programme: a cross between Cheers and The Wire, set and filmed in Merchant’s native Bristol, yet co-starring the very American Christopher Walken. Merchant plays one of seven strangers who meet during community service, a circumstance that leads them to forge unexpected friendships and tangle with gangsters and stolen money. He co-created the show with the US screenwriter Elgin James, who served time for actions committed while part of an anti-fascist group. The obvious differences in their lives were major factors in the show’s development.

“What if people from very different walks of life, who on the surface seem like archetypes, were forced to meet and work together?” Merchant remembers asking himself. “It’s quite a utopian idea, but it would help us make connections and progress forward, rather than retract into our bubbles. Those are important ideas in the divided times we live in. I love thrillers and dramas and playing with emotion, so for me the show is about trying to throw it all into the mix, and then hoping it’ll work out.”

The Outlaws marked the first time Merchant had filmed anything in Bristol, and the first time he’d gone home in years. “I’ll be honest, I was expecting to come back as a conquering hero,” he jokes. “Perhaps to a ticker-tape parade. That didn’t happen, but I’m assuming that’s because it was the pandemic and people weren’t able to organise one.” Shouldn’t he at least have a statue there by now? Cary Grant has one. “That’s right! Though I’d like to think, if mine was in relation to the Cary Grant statue, they wouldn’t have enough bronze to manufacture me,” he reckons, his 6ft 7in frame currently hidden beneath his desk. “Maybe it’d just be my head? That would be the dream, wouldn’t it?”

Merchant has lived on-and-off in LA since 2011, drawn in by its solitude and silence. Noise is confined to the coyotes that like to mate near his back garden, and he doesn’t often leave the house. “I don’t know if it’s laziness, but even when I was young, I was never the last person to leave a party,” he recalls. “I’ve just got to a position now where I don’t have to go anywhere if I don’t want to.”

Back then, he sensed that there would be more to his future than Bristol. Drawn to comedy, he’d found a hero in John Cleese, born 20 miles away in Weston-super-Mare and who’d, via Cambridge, the Footlights and the BBC, become a star. “He seemed like a local guy done good, and there was a part of me that thought that seemed possible for me as well,” he says. “I don’t know why. I don’t think I was an arrogant child, because it’s not like I was calm or super confident in other aspects of my life. I just couldn’t shake the idea that maybe I could do the same thing as him.” He did stand-up locally, studied film and literature at Warwick University, and worked in student radio. A job at XFM Radio in London followed, where his boss was the similarly ambitious Gervais. They began writing scripts together soon after.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

In his comedy, Merchant has a tendency to self-deprecate, or mock his own appearance. In series two of The Outlaws, his character Greg – a melancholic divorcee and lawyer by mistake – repeatedly humiliates himself in front of a co-worker he’s attracted to, loudly warning her about yeast infections. Later, he stumbles into a chandelier when he’s trying to be smooth, while one character calls him a “goggle-eyed plank”, a colourful put-down that joins others directed at Merchant characters of yore. Cameoing as Gareth’s friend Oggy, aka the Oggmonster, in The Office, he was dubbed a “big, lanky freak”. In the 2019 film Good Boys, he was accused of looking “more like a paedophile than anyone I’ve ever seen” by a preternaturally mean 12-year-old. Does he come up with these lines himself?

I didn’t even realise I had an accent until I went to university and people started mocking it

“Well, most of the insults would be written by me because the writers are too scared, obviously, to insult me to my face,” he says. “But that’s all born out of that John Cleese inspiration, of making fun of the physical attributes that you have. I have no vanity when it comes to comedy. I’m happy to embarrass myself, I find that funny. It’s not self-loathing. It’s just… why wouldn’t you make fun of that stuff?”

Much of it did start off coming from other people, though. “I didn’t even realise I had an accent until I went to university and people started mocking it,” he remembers. “And the idea that it wasn’t regarded as ‘proper’, and that it was kind of regional and had all this baggage. It’s amazing how people judge you for your accent. Imagine a prime minister with a thick West Country accent. Would they be taken seriously? It’s interesting.”

Merchant seems innately curious. Repeated throughout our conversation is the word “interesting”, which he uses when talking about class, sensitive jokes, typecasting, and how the socio-political underpinnings of The Office sometimes get overlooked. “I think there’s still cultural snobbery about drama, that it’s somehow worthier, or more difficult to make, or more profound in some way,” he says. “My stuff with Ricky and also stuff I’ve done separately, we’ve explored, I think, some quite interesting territory.” He doesn’t know why comedy is seen as somehow less-than, but he finds it intriguing to ponder. That approach also seems to be the key difference between him and Gervais – one gets worked up by the world, the other is fascinated by it. That’s clearer, too, when elements of their world-views merge.

As a celebrity on the internet, Merchant admits that he’s “quite dull”, a result of being skittish about causing offence. He remembers once being about to tweet about New Zealand, but then being unsure if the term “Kiwi” is problematic. “When you’re policing yourself in that way, because you don’t want the headache of it [if it goes wrong], it’s absurd to me.” Writing television, he adds, you have numerous people figuring things out behind closed doors and having the space to be thoughtful. The speed and brevity of Twitter, meanwhile, leaves no such room.

“I’ve become more and more cautious because I don’t want to get into a debate,” he says. “I don’t want to have to defend a tweet from 10 years ago. It’s not interesting to me to spend time defending a point of view or a glib joke that I made at 2am.” There’s lots about Twitter he doesn’t have time for. “This obsession with trying to police what people say, you know? It’s funny [because] when I was growing up, Mary Whitehouse was the version of that. The uber-religious [person] trying to get TV shows banned and newspaper articles retracted, and she was very much seen as a right-wing figure. Now it feels like it’s a lot more coming from the Left, and that suddenly the champions of free speech are Right-wing nutters. How did that come about? I don’t want to side with those people!”

It’s a mindset that’s vaguely Gervaisian, only expressed with significantly less rage and snark, making it nowhere near as annoying. It also leads to an obvious question: if Merchant finds social media discourse exhausting and the idea of debating random strangers online so tedious, what does he think Gervais gets from it? He ponders the question, stopping and starting his answer. “I think Ricky’s got a lot more… I think he’s braver than I am, and has a lot more of a rock’n’roll kind of attitude. I think he’s quite happy to give the finger to the world. I admire that about him. He doesn’t mind taking on the naysayers and the critics and engaging with that stuff. It doesn’t interest me in the same way. I find it tiring rather than energising. For me, it just seems so time-consuming.”

There’s more to his life, after all. He says that he’s ultimately a writer, and someone eager to explore new things and get to know different kinds of people. The Outlaws, for instance, has a writers’ room full of storytellers from different backgrounds to his own. “It’s how I, as someone who’s getting older and in theory more out of touch, can try and stay engaged,” he explains. “However much I read and educate myself about subjects, I’m never going to quite have the insight that people have who’ve lived them, and that’s interesting to me.”

Between The Outlaws and his chilling turn earlier this year as serial killer Stephen Port in the BBC docudrama Four Lives, is he striving for more seriousness in his work? “I am, I think. I’m more interested in darker themes and social themes, but I’m sure I’ll always be happy to fall into a chandelier for comic effect, too. I don’t think those things have to be exclusive. And all my heroes are a varied bunch, you know? Billy Wilder could do Some Like It Hot, but could also do Sunset Boulevard, which I think is a very profound meditation on ageing and celebrity and all sorts of things. I’ve got a broad taste.”

It’s a moment of thoughtfulness, one that quickly gets broken up by an interjection of trademark Merchant-ness. “It’s just that when you start out doing comedy, people think: ‘Oh, here he is – Mister Big Shot thinks he’s Dickens now!’ But, whatever. It’s just different interests.”

He shrugs his shoulders, a picture of unbothered, dull-on-Twitter calm.

‘The Outlaws’ series two begins on BBC One on Sunday 5 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments