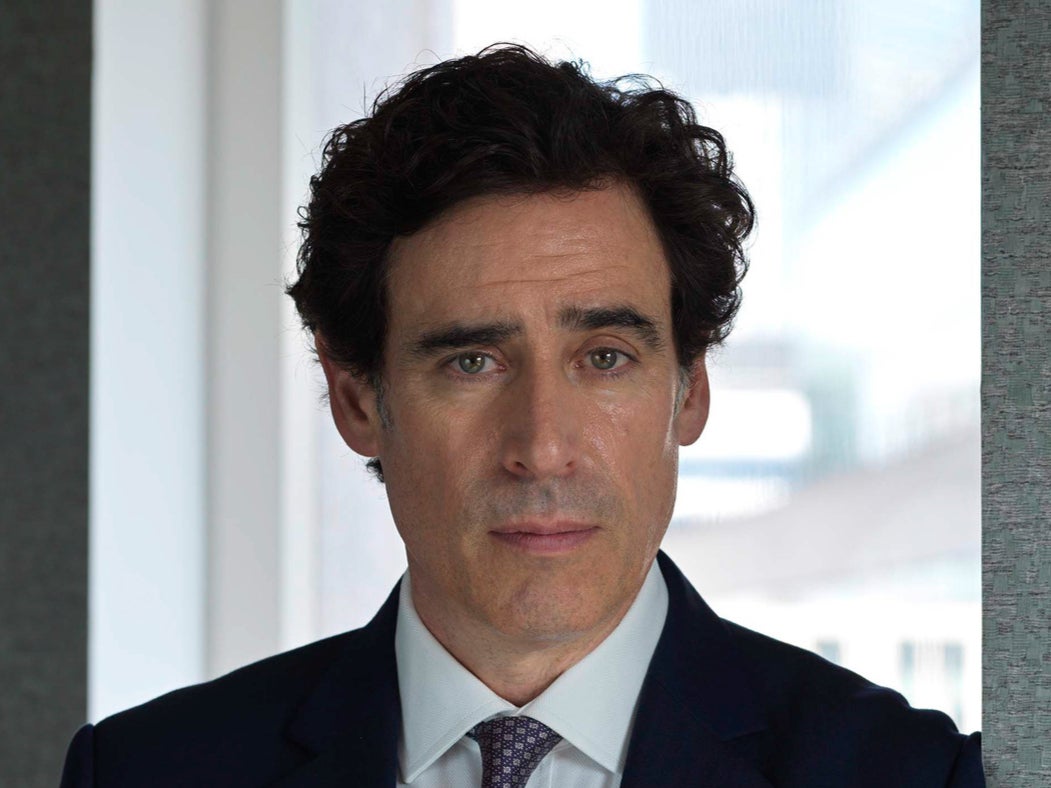

Stephen Mangan: ‘When I was watching my parents die, there were moments where things were funny’

The star of ‘Green Wing’ talks to Alexandra Pollard about the new series of ‘The Split’, the ‘ghetto-isation’ of TV and why losing his mother changed his path from law to acting

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“I don’t care what situation you’re in or what topic you’re talking about,” says Stephen Mangan, “humour can always be involved.” He is living proof of that – not just because he’s played sleazeballs, swingers and sex pests in some of the great comedies of this millennium, from Green Wing to Alan Partridge, but because he’s managed to find laughter even in his own worst moments.

“When I was going through the most traumatic and difficult times of my life, when I was watching my parents die,” Mangan continues softly, “there were moments where things were funny.” He was 22 when his mother died. She doubled over in the middle of dinner, was diagnosed with colon cancer, and died six months later. When Mangan was in his early thirties, a brain tumour killed his father just as swiftly. “Now you could stand at the side and go, ‘Oh you find it funny that your mum’s dying? You find it funny that your dad’s dying?’ No. But as a human being, that ability to find humour in the darkest moments can save you. In the bleakest, darkest moments, comedy can throw a light.”

As he speaks, Mangan’s grey baseball cap is pulled low over his face. He’s here to promote the new series of the excellent BBC divorce drama The Split – not a comedy, even if he can’t help but bring his natural wit to it – but it’s a teenage Mangan who greets me first. His Zoom profile picture is him at 19, with that familiar mischievous grin and mop of dark curly hair. “It’s disappointing when you see the real me,” says the 53-year-old version, slightly wearily, when he appears. I had wondered how he would seem; in interviews last year, Mangan spoke of feeling “low, hopeless and defeated”, a “profound sadness” set off by lockdown and the death of two close friends, fellow actors Paul Ritter and Helen McCrory. In the wake of that loss, he found himself not only grieving for them, but reliving the trauma of losing his parents. Ritter had a brain tumour. “What was so hard about seeing Paul get ill,” he told The Times, “was that it was so much like when my father got ill.”

Today, there is a slightly subdued air about him, and he doesn’t often lift his gaze to meet mine, but he is warm and quippy all the same. “I think the Brits, especially, understand dark humour and understand that it’s got its place,” he concludes. “Now of course, what one person finds appropriate and funny may appal someone else, and that’s OK.”

Green Wing’s Guy Secretan is a great example of that. The arrogant anaesthetist played puppets with bodies on operating tables, swore at children and manipulated women into going out with him. He was, depending on how you squinted, either a loveable lothario or an irredeemable misogynist. “He probably wouldn’t sit very well today,” the show’s creator and producer Victoria Pile said recently, “in the #MeToo era.” “He was such an arsehole,” concedes Mangan with a chuckle. “He was an arrogant, entitled prick. He was so much fun to do because he behaved in ways that I would never, ever behave with people – especially with women. It’s hilarious to suddenly be allowed to be that person when everyone understands, hopefully, that’s not who you are.”

Comedy has become Mangan’s forte. There’s something about that hangdog face and hint of a smirk that lends itself to playing supercilious posh boys whom you can’t help but be charmed by. The first role that had him recognised in the street – shouted at, in fact – was the Daily Mail-reading, Lexus-driving, threesome-loving Dan Moody in I’m Alan Partridge. In The Armando Iannucci Shows, the Thick of It creator’s early sketch show, he was a TV executive unable to understand anything unless it’s framed as a TV pitch. In Episodes, which saw him reunite with Green Wing co-star Tamsin Greig, he played a brow-beaten comedy writer trying to remake his cerebral British sitcom in LA. Winning Golden Globes, Emmys and a loyal fanbase, the series took droll British humour and gave it a glossy Hollywood sheen, with Friends’ Matt LeBlanc playing an unflattering version of himself.

The thing is, Mangan never really meant to be a comic actor. After he finally crossed over from theatre to TV in his thirties – more on that later – “the first people I fell in with were Armando Ianucci, Chris Morris and Victoria Pile”, he explains, “and I suddenly found myself being a comedic actor. That was suddenly my thing. I was a comic actor doing comedy.” He was, he says, “typecast” for a while. “Kenneth Branagh said he deliberately avoided doing any comedy early on in his career, because there’s no status in it. Great actors are ‘serious’ actors. Comedy actors, you don’t always get given that status, which is fine, but you’re always looking for interesting work. With The Split, it’s been a joy to do something different. It’s a type of part that I hadn’t really been offered that much – a dramatic, emotional part.”

Emotional it certainly is. There’s a lot of crying, shouting and mud-slinging where his character Nathan’s concerned, not to mention a hefty dose of adultery. Nathan is a barrister, the husband of divorce lawyer Hannah (Nicola Walker, as brilliant as ever). Their marriage unravels in chaotic fashion when it emerges that he cheated on her, to which she responds by embarking on her own drawn-out affair with her handsome Dutch colleague Christie, with whom she’d already had a brief fling years earlier. “I got a lot of stick for cheating on Nicola Walker,” says Mangan with a laugh. “People were very upset with me. They got quite heated. I found myself going, ‘Well she slept with Christie the night before our wedding! So, what about that?’ People were much more sympathetic after the second series.” The third takes an abruptly dramatic turn – but I’m not allowed to talk about it here, nor am I allowed to discuss it with Mangan. “I don’t think anyone would guess what happens,” he says, and we leave it there.

Just as the show’s creator Abi Morgan planned, this third series will be the last. “It’s about as long as this story should be,” says Mangan. “We don’t want 24 years of Nathan and Hannah trying to decide if they want to be married or not. You get series like Homeland, where the first series was extraordinary, and then because it was so popular, they had to suddenly think, ‘Well what do we do now?’” He stops short of passing judgement on the seven arduous seasons that followed, except to say, “You’ve got to know when to quit, I think.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Mangan is amazed how emotionally involved people are in The Split – himself included. “Stepping into a life that’s not yours – human beings love doing that,” he says. “We’re living that divorce through them. We’re thinking, ‘What would I have done?’ That’s why people get so hooked and end up crying watching a TV show that’s… not real! But we actually feel it. We sit there and we actually feel it. It’s sort of flattering to have people get that involved in something.”

Funnily enough, Mangan was heading for a career as a lawyer when he decided to veer off the path that had been beaten out for him by his parents. They were Irish immigrants who left school at 14, and “they placed, as a lot of immigrant families do, a huge store on an education”. So he went to boarding school in Hertfordshire, a zero-privacy experience that he describes as “like being on Big Brother”, then to Cambridge to study law. “The more time you’ve put into getting these qualifications, the more you’re like, ‘What was the point of doing that if you’re just gonna go off and wear jazz shoes and leotards for a living?’” he recalls. “I think fundamentally it was mum dying at the age of 45, her mum having died at 47, that was a real… Things came into focus suddenly. ‘I’m in my early twenties, I might have 20 years left, why am I thinking about becoming a lawyer when I really don’t enjoy law? I should become an actor, and then in a couple of decades’ time, I’ll play a lawyer on telly.’”

For me, acting is standing on a stage and saying stuff and having an audience respond. It just seemed such a romantic way to earn a living

He went to Rada, where he “spent three years shouting and crying in rooms”. He was, he reckons now, “hiding from the world a bit after my mum died, and not really knowing what to do and how to cope with it. It’s very safe and reassuring to know you’ve got another three-year course. I think I was in grief.” By the time he left, he was already 26. “Keira Knightley had had a 40-year career by the time she was 26,” he deadpans. “I was late to the game. And then I went and did nothing but theatre for five years.”

Why just theatre? “That’s the thing you do when you’re growing up. I wasn’t in a six-part series at school. For me, acting is standing on a stage and saying stuff and having an audience respond. It just seemed such a romantic way to earn a living. To be going along to your dressing room in the evening, getting into your costume and going out in front of an audience, doing a show, and then going out afterwards. That’s the life I wanted. And I wasn’t really interested in being famous.” His agent even rang him about an audition for a Merchant Ivory film. “I was like, ‘I don’t wanna do that.’” Instead, he acted on Broadway and in the West End, toured across the world in Much Ado About Nothing, and starred in a Tony-nominated production of the Alan Ayckbourn trilogyThe Norman Conquests.

Eventually, he realised that other artforms were just as worthy. “Yes, the parts you play are important but it’s the people you’re working with really,” he says, “and there’s lots of interesting and talented people working in television.” Even more so today, you could argue. In the age of streaming, it seems like television has never been better – both in terms of choice and representation.

Mangan only half agrees. “I think it’s going in both directions at once,” he says. “There’s never been more choice and more range of stuff being made, but I think that’s also leading to ghetto-isation. If you’re only into police dramas, you can watch those shows from morning to night without a pause. We’re all going into our own bunkers, echo chambers. And if you don’t like a show, all this ridiculous kind of… yeah.” Go on. “No, I suddenly stopped myself,” he says. “It’s too boring. But you can hear the views you wanna hear, echoed back to you endlessly now, and that can’t be good. It can’t be good. Nothing is more dangerous than a belief that your view is the right view, that the way you live your life is the right way to live. The closing down of ourselves and the narrowing of our experiences can’t be good.”

At its best, though, TV, just like theatre and film, can be a machine for empathy. It’s why people cry watching The Split when they know it isn’t real. “That’s all art really is,” says Mangan, “trying to imagine seeing the world from someone else’s perspective. Even if it’s imagining that you’re Thor with rippling muscles, or Phoebe Waller-Bridge in Fleabag.” He laughs. “It’s incredibly healthy.”

‘The Split’ series three starts on Monday 4 April on BBC One

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments