A troubled enterprise: How Star Trek: The Motion Picture flirted with disaster only to become a surprise smash

As ‘Star Trek: The Motion Picture’ celebrates its 40th anniversary, Ed Power looks back on how the big screen adaptation weathered on-set issues to become a record-breaking hit

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Star Trek: The Motion Picture is science fiction’s ultimate Rorschach test. Some Trekkies regard the saga’s big-screen debut, which marks its 40th anniversary this week, as a morose mess and lumbering betrayal of everything the zippy and optimistic TV original stood for. Others see it as a brave but flawed attempt to bring Kubrickian depth to the adventures of Captain Kirk and Mr Spock. A tiny minority of us regard it as a misunderstood masterpiece.

What everyone agrees is that it was a miracle the film reached cinemas on 7 December 1979 in the first place. Beneath those swooping Starship Enterprise contours, the undertaking had been a roiling mess. Egos, in-fighting, a director who didn’t care for Star Trek, a cast that cared too much – together it conjured a perfect intergalactic storm.

The biggest impediment of all was the huge ticking clock looming just off-camera. Paramount Pictures had rushed The Motion Picture into production in the spring of 1978. The hope was to cash in on the sudden and, as the industry saw it, baffling, popularity of epic space operas. Come hell, high-water or Klingon invasion, Star Trek was to have a piece of the interplanetary pie. Nothing mattered beyond TMP making its Christmas 1979 deadline.

“I don’t care if the story doesn’t make sense, I don’t care if it cuts together,” Paramount chief executive Barry Diller had told his board months before the scheduled release date as it became clear the film might well arrive as an incoherent shambles. “We’re delivering this movie. Period.”

Star Wars had in 1977 recast the box office in its own image. With X-wing contrails streaking the sky, Paramount was rushing to catch up. Of course, it already had a ready-made Star Wars of its own.

Star Trek had, since its cancellation in 1969, gone on to achieve a cult fanbase thanks to endless repeats. Prior to George Lucas’s Jedi juggernaut, Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry had struggled for years to revitalise his franchise. And in the face of Roddenberry’s lobbying, Paramount eventually relented, with Diller suggesting a new series, to be titled Star Trek: Phase II.

Later, it was decided to bump this up to a one-off movie with a low-ball budget of around $3m (quite a turnabout as Paramount had initially vetoed Roddenberry’s suggestion of a film, insisting instead on a return to TV). Then Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader unleashed their death-ray upon cinema.

“Star Wars woke them up to the fact that these things I’d been telling them for a number of years were true,” observed Roddenberry. “There was an audience for millions of people out there who are interested [in space opera].”

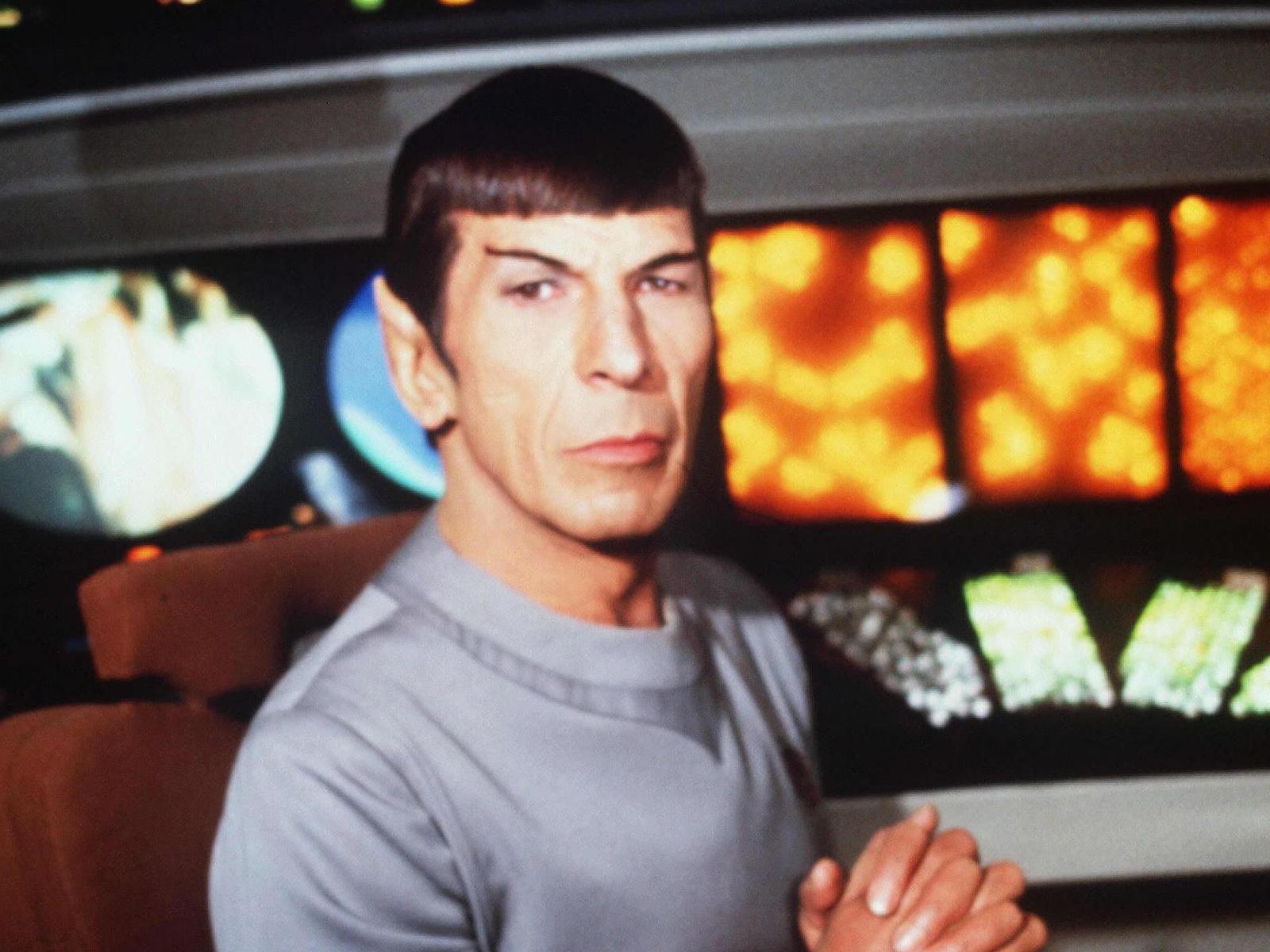

Paramount was determined Star Trek serve up a spectacle no less jaw-dropping than that delivered by Star Wars. So it parachuted in hotshot young executive Jeffrey Katzenberg (later to found DreamWorks with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen). His first challenge – the one on which the rest of the endeavour depended – was convincing Leonard Nimoy, aka Spock, to sign on.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“To relaunch Star Trek without Leonard Nimoy is to buy a car and not have wheels,” Katzenberg would reflect. “It just seemed impossible... Illogical.”

But it seemed perfectly logical to Nimoy, the only original cast member to have turned down the opportunity to star in Roddenberry’s Phase II. As a serious actor, he was dismayed to have become synonymous through the Seventies with his pointed-eared alter-ego. And he had simmering beef against Paramount, which had, without his permission, plastered his likeness all over its lucrative Star Trek merchandising.

Katzenberg was determined get his Vulcan, though. So he flew from Los Angeles to New York where Nimoy was appearing in a Broadway run of Equus. He materialised backstage one night as Nimoy was preparing to go on. Flattered that so powerful an executive had travelled cross country, Nimoy agreed to meet for coffee.

Nimoy was in the process of suing Paramount for what he believed to be his fair share of the Spock merch revenue. Katzenberg suggested that he proceed with the lawsuit but also come back into the Trek family. Nimoy put his cup down firmly. “I just can’t do that I’m sorry.”

Money in the end talked. Katzenberg told Diller to swallow his pride and open his cheque book. With the studio prepare to settle, Nimoy realised he had no choice.

He wasn’t especially thrilled to go back to Star Trek. Yet, if he continued holding out, he would be painted in the press as the villain who had crushed the dreams of an entire generation of Trekkies (or Trekkers – as some Trekkies preferred to be called). Every time he went out to promote a new project one subject would inevitably come up: why did you say no to Star Trek?

“How could I answer those questions?” he said later. “I didn’t like the script? I hated Gene? I was angry at the studio? I would be carrying that negative s*** around with me for the next five years at least.”

With Nimoy signed on, Paramount now had a full flush of stars. William Shatner had been eager to reprise the part of Captain James Tiberius Kirk (his once luxuriant quiff replaced with what looked suspiciously like a brillo-pad hairpiece). DeForest Kelley was back, too, as Doctor Leonard McCoy, while fans would have the opportunity to reconnect with communications officer Uhura (Nichelle Nichols), helmsman Sulu (George Takei), Lieutenant Commander Chekov (Walter Koenig) and Chief Engineer Scott (James Doohan).

The March 1978 press conference announcing the return of the original cast was the largest Paramount had held since Cecil B DeMille revealed he was making The Ten Commandments. It was intended as the first salvo in an open-ended charm offensive.

Long before internet-fuelled fandom, Paramount was aware that Star Trek had a huge and demanding following. A 1976 letter-writing campaign had persuaded Nasa to rename its first Space Shuttle “Enterprise”. Star Trek devotees possessed clout and were keeping a close watch on The Motion Picture.

They will have noted that Paramount was determined to expand beyond the parameters of the original series. Joining the old hands was newcomer Stephen Collins, playing preppy Captain Willard Decker (Collins’s career would end in disgrace after he admitted to “inappropriate sexual conduct with three female minors”). The cast was rounded off by Indian supermodel Persis Khambatta as Ilia. Her character was a Starfleet navigator belonging to the hairless Deltan race, who becomes possessed by a destructive alien entity – V’ger – which threatens all life on earth.

As for the director, Paramount chose 64-year-old Robert Wise, the studio veteran who oversaw The Sound of Music and West Side Story. He had sci-fi (and sci-fi adjacent) credibility, having directed black and white classic The Day the Earth Stood Still and the tense Run Silent, Run Deep.

What he hadn’t done was watch an entire episode of Star Trek. The little he had seen he actively disliked. Still a gig was a gig and he agreed to park himself in the captain’s seat. It became quickly clear, though that he regarded this as simply another pay cheque, rather than an opportunity to immortalise Kirk and the gang on the big screen.

“Robert was a kind of strange choice for director,” observed Richard Taylor, the movie’s art director. “He ... wasn’t really a science fiction buff. He’d rather do Sound of Music. He was older and he would sit there on sets and drift off and then have a masseuse keeping him awake. I don’t think he was ever very enthusiastic at all about directing the movie. He was wrangled into it and made good money doing it. He was not passionate, it was a job.”

The biggest impediment, though, was that, in order to meet the Christmas 1979 deadline, the production began without a completed script. Roddenberry’s episode treatment for the pilot of the now-cancelled Star Trek Phase II had been bumped up to a screenplay. In the rush to get it into production, however, nobody had got around to writing a satisfactory ending.

The story begins with the Enterprise in dry-dock above earth after an extensive refit. Word reaches Starfleet of a mysterious entity – the aforementioned V’ger – on a collision course with Earth and obliterating everything in its path. With the desk-bound Kirk, now an admiral, parachuted in as commander, the Enterprise and all our favourite crew set off on an intercept course.

So far, so Star Trek. But nobody had the foggiest how to resolve the tale of V’ger and its long journey across the galaxy.

“Here’s this gigantic machine that’s a million years further advanced than we are,” agonised screenwriter Harold Livingstone. “Now, how the hell can we possibly deal with this? On what level? As the story developed, everything worked until the very end. How do you resolve this thing? If humans can defeat this marvellous machine, it’s really not so great, is it? Or if it really is great, will we like those humans who do defeat it? Should they defeat it.”

With the basic plot still in flux, the cast were advised not to bother learning their lines from the final third of the screenplay (Roddenberry was meanwhile eased out and ultimately expunged from his own franchise). The “final” draft was not presented until September 1978. With input from Shatner and Nimoy, it had been decided the movie should conclude with V’ger becoming one with its creator.

The twist is that V’ger was the Nasa space probe Voyager 6, an update of the original 1977 Voyager probe. Discovered by a race of sentient machines, it had achieved consciousness and was now on a mission to meet its maker. That, of course, was humanity. The film ends with machine and human – in the form of Ilia and her old boyfriend Decker – merging to create a new life-form.

This was a satisfying conclusion. It re-imagined Star Trek as 2001: A Space Odyssey for slow learners essentially. And still the tweaking continued. Shatner, especially, felt he knew Kirk better than either the director or the writers and so chimed in with his own revisions. By March 1979, six months before release date, only 20 pages of the original 150-page script had been retained.

Star Trek’s special effects were a disaster too. The original plan was to hire FX wizard Douglas Trumbull. Unfortunately, he was busy on Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. So Paramount instead turned to special-effects house Robert Abel and Associates, which specialised in advertising. Five million dollars was required to rush through all the necessary shots, Abel told Paramount. However, he over-reached in championing complicated graphic imaging systems that were too far ahead of their time. The months clipped by without any of the elaborate special-effects sequences completed.

“They made some really big, fundamental mistakes in trying to pre-vis on computers that weren’t ready for prime time,” said Trumbull, charging to the rescue having wrapped Close Encounters. “They spent a year and nothing was finished, and nothing worked.”

Trumbull informed Diller that he could complete the FX by deadline – but that it was going to cost Paramount. The studio had little choice. Cinema chains in the US had coughed up advance payments of $30m on the understanding Star Trek would open on 7 December. Miss that window and the studio faced multiple lawsuits. Quicker than you could say “beam me out of here, Scotty”, the budget had ballooned from the initial projection of $18m towards $45m.

“We are so tight, even now,” Wise told a reporter from Starlog sci-fi magazine visiting the set in the final weeks of the shoot. “If a strike by the stage hands – which has been threatened – lasts more than a couple of days, we won’t make it.”

Everyone involved assumed they were party to the birth of an interstellar turkey. Many feared their careers would be ruined. Star Trek’s legacy, it appeared, had been permanently tarnished.

These concerns seemed vindicated by early reviews. Time magazine grumbled The Motion Picture took “an unconscionable amount of time to get anywhere, and nothing of dramatic or human interest happens along the way”. Harlan Ellison, the science fiction author who had written for the original series, described it as “Star Trek: The Motionless Picture”.

The public begged to differ. Far from a suffering a black Christmas, Star Trek: The Motion Picture set a new record for a first weekend in December gross, bringing in more than $11m. Ultimately, it would earn more than $139m and three Oscar nominations (for best original score, best visual effects and best art direction). Despite being released at the very end of the year, it was the fifth highest-grossing movie in America in 1979.

In the end, Star Trek: The Motion Picture achieved a sense of slow-burning wonder. It’s a languid watch – light years from the cheerful, romping TV series. But V’ger, an all-knowing machine with a childlike desire to reconnect with its maker, is a fascinating antagonist. And unlike 2001: A Space Odyssey, the film to which The Motion Picture is unashamedly indebted, the conclusion makes sense on first viewing – even if you’re a six-year-old who has scoffed too many Opal Fruits.

In particular, it’s hard not to feel a lump in your throat when Ilia and Decker stand face to face, their souls merging as Jerry Goldsmith’s remarkable score swells. Moreover, The Motion Picture’s success against towering odds opened the door for the greatest Trek of them all, 1982’s Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Without this weird, ponderous, often very moving epic, Star Trek might never have gone on to live long and prosper as emphatically as it has.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments