How each incarnation of Sabrina the Teenage Witch is symbolic of feminism through the years

The new ‘Chilling Adventures of Sabrina’ represents an era where the witch has become emblematic of women’s battles to claim ownership of their bodies and their identities, says Clarisse Loughrey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sabrina Spellman has returned to our TV screens, but not as we remember her. There are no more hair comb headbands and tubes of lip gloss, no more wisecracking asides from the pet cat. The Sabrina of today has swapped it all for blood sacrifices and devil horns. Netflix’s new Riverdale spin-off, Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, reimagines the character so fondly remembered from the 1990s sitcom Sabrina the Teenage Witch as full-blown occultist; her worries about good grades, popularity, or her boyfriend Harvey Kinkle are now mildly overshadowed by her daily dealings with Satan.

The cultural image of the “witch” has always been in flux, and Sabrina is no exception. For centuries, the “witch” has served as a metaphorical stand-in for the mysteries of womanhood, interpreted, in turn, as a source of fear or a well of empowerment – sometimes both at the very same time. Sabrina herself has evolved from a figure of harmless, contained femininity to a symbolic reclamation of witchcraft and its history of persecution.

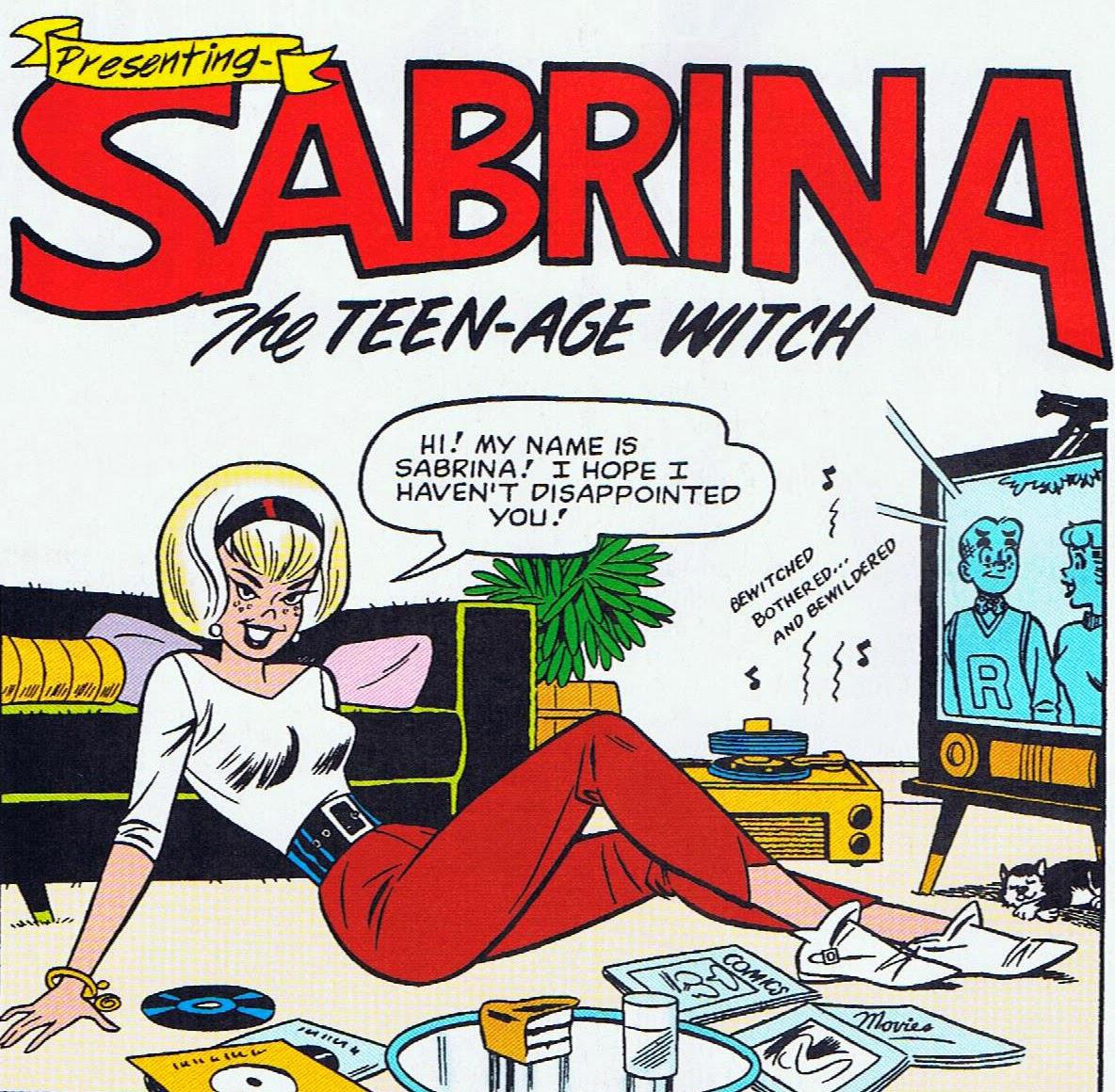

The Netflix series is based on a comic book series of the same name – created for Archie Horror, an imprint of Archie comics, in 2014 by Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa and Robert Hack – exploring the fairly obscure origins of the character. Indeed, Sabrina was first conjured up by Archie Comics’ own George Gladir and Dan DeCarlo, back in 1962 – decades before Melissa Joan Hart starred in the TV sitcom version, which ran from 1996 to 2003. The duo had envisioned her as a thoroughly modern witch, a little more hip and flirty than Bewitched’s Samantha Stephens, but as well-intentioned in her actions. Both of these characters reflected the 1950s and 1960s popular image of the witch as a kind of perfected femininity: mischievous, sexually attractive, but ultimately obedient to the patriarchal structure. In her first issue, as the lead story of Archie’s Mad House issue #22, released in October 1962, Sabrina lays out the rules of her powers: she’s unable to cry and, if she falls in love, she loses her powers. In short, she’s a party girl with zero emotional baggage.

Yet, at the time, there was a duality to the image. While the witch may have concerned herself with keeping her boyfriend or husband happy – as a reassurance to men everywhere that the mysterious powers of womanhood could ultimately be tamed – her powers still promised an independence and agency that far exceeded a woman’s usual circumstances. Sabrina’s mischief, from fixing sports games to spiking milkshakes with love potions, was an expression of subversive power that could still work within the system.

Sabrina became the star of her own series of comics, titled Sabrina the Teenage Witch, with an accompanying animated series airing between 1970 and 1974 as part of CBS’s Saturday morning programming. However, her next onscreen appearance would be the 1990s sitcom of the same name, which ran on ABC for its first four seasons (1996-2000) as part of its highly popular, family-friendly TGIF lineup, alongside the likes of Boy Meets World and Clueless. The show was then cancelled by the network and subsequently picked up by The WB, which aired three more seasons tracking Sabrina’s college years. By the time Sabrina the Teenage Witch officially ended in 2003, the show had lost more than half of its viewership.

Relatively little about Sabrina’s circumstances changed since the 1960s: she was still a “half-witch”, with a mortal mother and a witch father, who lived with her two magically gifted aunts Hilda (Caroline Rhea) and Zelda (Beth Broderick) and a cat named Salem who, in fact, was a witch trapped in a feline body as a punishment for his misdeeds. While the Salem of the 1960s could express himself only in “miaows”, a tradition continued in the 2018 version, this Salem was a self-hating, sardonic, emotional-eater who had all the show’s best jokes. Sabrina still had a mortal boyfriend named Harvey Kinkle (Nate Richert) who, for the majority of the series, remained naively unaware of her true nature. Her intentions were still pure, with her powers used mainly to aid her friends and family, or to help her solve the usual teenage troubles.

However, the Sabrina of 1990s certainly didn’t exist for the reassurance of men. Although there are limitations to how well Sabrina the Teenage Witch stands up against today’s ideals (the lack of non-white characters is glaring, for example), at the time, Sabrina represented the peak of 1990s “girl power”. That was a manifesto most famously issued by the Spice Girls, of course, but also manifested in a string of ultra-capable female characters who drew on supernatural elements to underline their unstoppable potential – think Charmed, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, or Xena: Warrior Princess.

A study by Rachel Moseley, researcher at the University of Warwick, found that, by the early 2000s, shows like Sabrina and Charmed had created a direct association between witchcraft and the notion of “girl power”. She wrote of her findings: “Historically, witches have been outcasts and much of this unease clearly stems from a fear of female force. The teenage witch genre articulates a new powerful image of femininity. It’s not that the Hag and herb potions have become hip, rather witchcraft has become synonymous with power and girly magic.”

This Sabrina was one who could balance it all and be anything (and everything) she wanted to be: an A-grade student with a keen interest in science and maths, a fashion mogul, a fighter of injustice, and a figure respected by both students and teachers. The episode “Dummy for Love”, for example, sees Sabrina fight for her free speech when Vice Principal Kraft (Martin Mull) demands she retracts an editorial bemoaning the school’s obsession with sports. Sabrina’s aunts also acted as strong role models, from Zelda’s scientific research, which at one point resulted in her summoning both Marie and Pierre Curie for help, to Hilda’s love of classical music.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

The show’s creator, Nell Scovell, explained that she was motivated to create the series in order to reflect what she would have loved “as that weird young girl who grew up to write for Letterman and Spy and The Simpsons”. However, Sabrina was not only someone for smart, funny girls to relate to, she was someone they could look up to and emulate as well. The “girl power” image extended offscreen, too, in the series’ majority female cast, majority female writers room, and in its female showrunner. The witch was still, in a way, an image of perfected femininity, but one now finally under the control of women, who could use it project their own ideas of empowerment.

In the following decade or so, since Sabrina the Teenage Witch dropped off the air, the “girl power” image has lost some of its relevance. The approach has become more conflicted, more self-reflective, as a greater emphasis has been put on critiquing the social structures that placed limitations on women, as opposed to simply trying to ignore them. That, in part, has also seen a greater and more direct interrogation of the image of the “witch”. While the Sabrina of the 1990s had little correlation with any real practice of witchcraft, as she mostly just had to point her finger to get things done, recent representations of witches have drawn more directly from the occult, including American Horror Story: Coven, The Witch, and The Love Witch. In turn, this has helped align them with, and help them respond to, the historical misogyny which has attached itself to the word “witch”, drawing a line all the way back to the Salem witch trials.

And so, Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, both the comic and Netflix series, takes a far darker and more conflicted approach to ideas of witchcraft and magic. Sabrina faces a choice: she can undergo the “dark baptism” to receive her powers, but, in doing so, will submit herself to what she knows is a patriarchal system with the Dark Lord as its figurehead. This is the Sabrina that represents an era where the “witch” has become symbolic of women’s battles to claim ownership of their bodies and their identities. Something that can’t just be done with the flick of a finger.

Chilling Adventures of Sabrina is on Netflix now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments