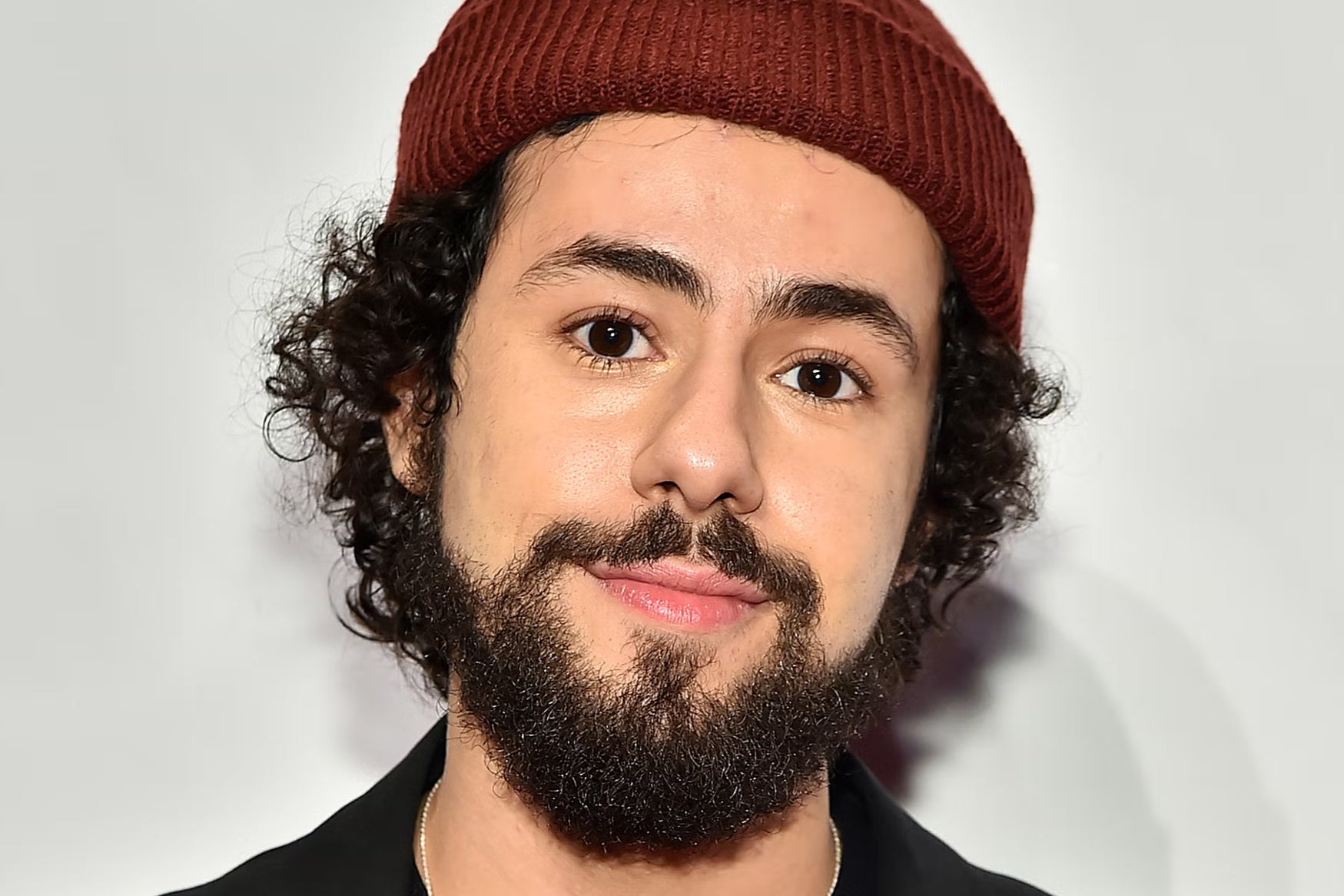

Ramy Youssef: ‘There’s no, “Yo, Muslims, here’s your show”’

The co-creator and star of ‘Ramy’ talks to Adam White about his semi-autobiographical comedy, why it’s not intended to cater to one ‘collective Muslim community’, getting stuck in acting purgatory, and why so many talented people of colour have to write vehicles for themselves to make it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As he collected the Best Actor in a Comedy Series award at last year’s Golden Globes, Ramy Youssef thanked God. The 29-year-old had just won for the lightly autobiographical Hulu series Ramy, which follows the travails of a first-generation American Muslim-Arab in his native New Jersey. (It’s just begun showing on Channel 4 in the UK.) At the sound of the word God, though, there was nervous laughter. Some of it was down to host and insistent atheist Ricky Gervais, who, minutes before, had moaned about awards-show winners thanking God in their speeches. More of it, Youssef suspects, came from people unsure how to respond to acts of religious earnestness.

“When you look at what the industry of religion has done over the last hundred years, it’s pretty atrocious,” he says, reclining on a sofa at home in Los Angeles. “Genuine spirituality has been stripped from the industry of faith. The way the church or the mosque or the synagogue operates in public and political spaces has been very devoid of sincerity. It kind of does deserve a laugh if you don’t know the stories.”

Youssef’s memory of the moment speaks to his good nature. Negative energy seems to bounce off him – Gervais wasn’t being mean; the crowd’s giggles were valid; God is great. Youssef appears on our Zoom call early in the morning, and apparently far earlier than he normally gets up, yet he’s powered by a natural ebullience. Wearing shaggy loungewear and a blue beanie, he looks more like the kind of guy you’d find stoned in Seth Rogen’s basement than a teetotal, practising Muslim. While he does swear and curse and have premarital sex, Youssef is otherwise God-fearing. Those typically disparate personality traits are what make him, and his TV alter-ego, so compelling.

Ramy is about religious sincerity and everyday blasphemy sitting side by side. Is it OK to find your own path within faith? Are you a disappointment? Who, when it really comes down to it, are you? Youssef’s character, named Ramy Hassan, wants to be a better Muslim, or at least better at understanding his faith. He’s eager to find love and a career he’s passionate about, but also has a habit of lethargically masturbating instead of looking for either of them. “He’s the unfulfilled me,” Youssef explains. “The show is about the tension between the higher self and the lower self, between who you are and who you want to be.”

Growing up, he didn’t see Muslim characters in film or television with similar anxieties. “I felt we were either seeing the terrorist stuff, or young men trying to separate themselves from their family and from their culture. Like, ‘Hey Mom and Dad, we’re not in Pakistan any more – I’m going to the prom and getting drunk, f*** you!’. I knew I was interested in portraying something that was genuinely synthesising all of that.”

In its earliest episodes, Ramy is driven by themes of millennial angst and cultural confusion. In one, Ramy breaks up with a Muslim girl after she asks him to choke her during sex. In another, he alienates a Jewish date because of his refusal to do drugs. Gradually, the show’s world view opens out and its themes deepen. One masterful episode is set in 2001: it sees the young Ramy experiencing puberty at the same time as the attack on the World Trade Centre, and later hallucinating Osama Bin Laden at his kitchen table.

Other episodes are anchored by family members and associates – from Ramy’s immigrant parents, who experience their own personal melancholies, to his sister, who is struggling as a twenty-something virgin. Racism, sexuality and disability are all folded into the storytelling with sensitivity. By the show’s second season, which introduces Oscar winner Mahershala Ali as a charismatic Sufi sheikh, Ramy himself has gone from a hapless singleton to someone who is often self-involved, and occasionally outright cruel. It’s a brave evolution, and one that’s been met with unease by some fans.

“I can feel a desire from some people that Ramy should be this ambassador of kindness and clarity, because people know so little of us,” Youssef sighs. “I mean, the real solution is that there would be more than one show with Arab Muslims in it. But because there’s so much pressure as to what the ‘good immigrant’ should be, it puts the show in an inherently frustrating position for everybody involved. The representation that I care about is emotional representation. This is a true emotional representation of the type of confusion I know many Arab Americans and, specifically, Arab-American men go through.”

Ramy was partly the product of its creator’s frustrations. Youssef, who grew up in New Jersey and studied political science at university, found acting success early. Drama classes in New York resulted in a gig on a Nickelodeon sitcom, See Dad Run, which brought him to Los Angeles at the age of 22. Once the show came to an end, however, he found himself stuck in what he dubs “acting purgatory”. “I would go into auditions and they’d be, like, ‘Oh, we thought you were brown,’ and I’m like, ‘I am,’ and they’re like, ‘Well, you don’t look quite as brown as we wanted.’ They’d try and get you to put on accents and stuff.” He’s quick to add, though, that he wasn’t above seeking out such roles. “I auditioned for all those things!” he laughs. “I just never got them. It was not a matter of principle, I was just straight-up rejected.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Instead, he honed his creative interests on stage, toured as a stand-up, and performed on Stephen Colbert’s US talk show. His first five-minute set, in which he joked about turning 30 and getting a Hogwarts-style letter from ISIS (“Yeah, cool, do I get a wand?”), went viral. That got him in the door at various cable networks, where he and three of his regular collaborators (including the comedian Jerrod Carmichael) pitched Ramy. After the concept was bought by streaming platform Hulu, Youssef ended up writing most of the episodes. He’s directed a handful of them, too. It’s something he shares with a wave of young multitalented artists of colour, from Issa Rae (Insecure) and Michaela Coel (I May Destroy You) to Aziz Ansari (Master of None) and Donald Glover (Atlanta), all of whom have achieved great success via television they’ve made themselves. It’s a difficult trend, though, that seems to suggest that creatives of colour can draw the same rave reviews and massive audiences as their white peers, but only after putting in far more work.

“Someone sent me an article that I thought was pretty thoughtful,” Youssef remembers. “It was looking at some people of colour who’d won Golden Globes, and it was me, Donald, Aziz and [Black Monday star and producer] Don Cheadle, and they just noted how, like, we’re all doing four jobs. For [all] of us, it’s not this thing where the vehicle’s just there for you. Personally, I don’t know how to feel about that fact.”

He begins to speak carefully, scratching at his beanie. “I don’t find it to be sad or anything, because I feel very gratified to be able to create the thing that I wanted to make. But the idea that there weren’t just things kind of baked and ready to go [for us]... I don’t know. The only way [forward] is to have people from different communities break into writers’ rooms and have influence in that way to create different worlds. And that’s what we’re doing.”

For now, Ramy stands alone. There are other US shows with Muslim characters, but Islam has never been as integral to the story as it is here. Frustration only breaks Youssef’s sunniness when talk turns to Ramy’s role in the wider cultural consciousness. He resists any claim that his series is groundbreaking. “I’m kind of agnostic to that kind of labelling,” he says, adding that the lack of a “centralised state” in Islam, or something that acts as its Vatican, means that it’s impossible to cater to one collective “Muslim community”.

“There’s no, ‘Yo, Muslims, here’s your show,’” he jokes. “This show is about a guy in New Jersey who jerks off too much and who is Muslim, but like, Muslim is number three on that list. We do assign deeper meanings to shows and comedies, but it’s important to understand how loaded that can be.”

He brightens again, flashing a grin from behind his facial fuzz.

“This is truly just a show, and I’m just Ramy.”

Ramy continues on Fridays at 11:05pm on Channel 4, with episodes available to stream on All 4

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments