The Little Drummer Girl: Why Park Chan-wook is a strange yet perfect fit for the BBC's new John Le Carré thriller

The 'Oldboy' director is known for many things – intense violence, stylistic showboating and lush eroticism – but would not have been the bookies’ favourite for a glossy new Sunday night thriller. Ed Cumming explains why the Korean auteur is the right choice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fans of Park Chan-wook dropped the marmalade – or possibly the kimchi – when they heard he was to direct the latest BBC John Le Carré adaptation, The Little Drummer Girl. The Korean auteur is known for many things – intense violence, stylistic showboating and lush eroticism – but would not have been the bookies’ favourite for a glossy new BBC Sunday night thriller. Imagine Wes Anderson doing Sherlock, or Hitchcock’s Doctor Who, and you get some sense of the mix of anticipation and anxiety involved. As a fan you want it to be good but you worry, too: what if this thing, by a filmmaker I love, inspired by a novelist I love, turns out to be a disappointment?

Park's most famous work is the Vengeance Trilogy, a thematically linked but non-sequential run of films released between 2002 and 2005 that he wrote and directed. The second of those, Oldboy, won the Grand Prix at Cannes in 2004 and announced Park to the world. “You can basically split my career into before and after the win,” he said in an interview last year.

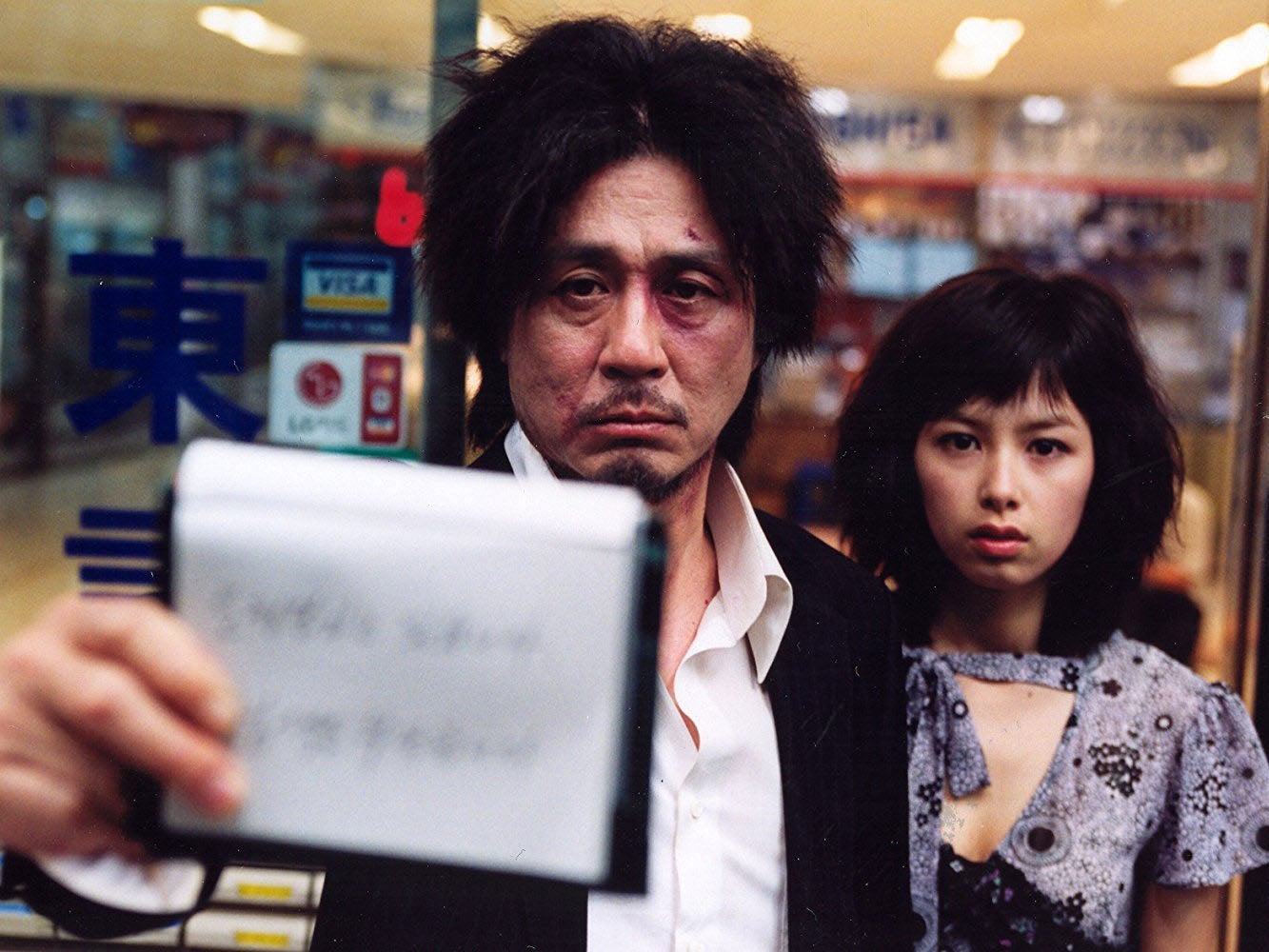

The film told the story of Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik) a businessman who is imprisoned for 20 years, apparently at random, and then released just as abruptly to go on a rampage of revenge. It calls to mind the work of Quentin Tarantino, who was president of the jury that year, but it has a richer and deeper heart. In 2013, there was an American remake of Oldboy, directed by Spike Lee and starring Josh Brolin, but it was dreadful.

Unlike with Tarantino, however, the violence in Park's films is never for its own sake, or for pure entertainment. It feels like the result of characters forced into extreme situations. Often it is beautiful. There are plenty of memorably visual moments, in Oldboy notably a sequence where Dae-su eats a live octopus and another where he defeats a whole corridor of goons using a hammer, but they usually are an extension of something deeper in the character.

The first film in the series, Sympathy for Mr Vengeance, follows a deaf-mute factory worker, Ryu (Shin Ha-kyun) desperately trying to raise money for a kidney transplant for his sister. It is patchier than Oldboy but it is a clear sign of his themes. Through intense idiosyncratic encounters, his characters ask the grandest questions of all: why are we here? What's the point of it all?

Born in 1963, Park grew up in Seoul and initially planned to be an art critic before an encounter with Vertigo turned him on to film. Before 2000's Joint Security Area, his first Korean hit, he continued to write reviews to pay the bills, but he has said he was never much of a critic. He always had one mind on his filmmaking career and did not want to upset the industry. Yet at the same time the critical streak in his work is obvious. Of Hitchcock, he has said “they are genre films, they have a surreal element to them, and they contain a certain sense of absurdity. In the most unexpected moments, he would dole out mischievous or very cruel humour.”

There is plenty of cruel humour and mischief in Park's most recent film, The Handmaiden (2016), a sumptuous, thoughtful masterpiece which won the Bafta for best foreign language film. Where the earlier work tended to use violence, The Handmaiden has sex, and shows the director's full range.

It was inspired by the novel Fingersmith, by the Welsh author Sarah Waters, with the setting transposed from Victorian Britain to the Japanese occupation of Korea, which ran from 1910 until the end of the second world war. Split into three distinct parts, it ostensibly tells the story of a conman, Count Fujiwara (Ha Jung-woo), who plans to use a young housemaid, Sook-hee (Kim Tai-ri), to seduce a wealthy heiress (Kim Min-hee). The two women begin an affair with an explicit sex scene, which caused controversy when the film was released. On first viewing, it appears titillating, or even borderline pornographic. Like the moments of extreme violence in Park's previous films, however, by the end of The Handmaiden it is revealed to be far more complex and knowing than we first suspect.

"A film director asks questions of the audience,“ Park said in an interview in 2016. ”And modern audiences often fail to respond to questions being asked. So you have to use shocking and stimulating things to stimulate them. It’s about the people – the public. They want more stimulation. You know, in an action movie they want more cars to be smashed. I think it’s the same when you’re asked philosophical questions, artistic questions or moral questions. You need more stimulation for them to respond."

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

To achieve this subtle effect through unsubtle means, Park's signature technique is to reveal causes and motivations only after showing the events they provoke.

The audience's initial reaction to an extreme visual is slowly subverted by the context that emerges afterwards. Sometimes they feel like plot twists, but not always. Frames and camerawork that looked purely aesthetic were in fact deployed for specific narrative purposes. What we think we see, in other words, is only a small part of the story. It's the theme of Le Carré's novels, too.

Over six episodes of The Little Drummer Girl, Park has all the space he could want to set up our expectations and then confound them. He might be a surprising choice for a BBC spy thriller, but he is very good fit. Even in the first instalment you can feel him toying with our attention, lingering on objects or faces, his camera as unreliable a narrator as any of the slippery agents it depicts.

The Little Drummer Girl begins on BBC One on Sunday 28 October at 9pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments