Joshua Jackson: ‘I think the process of not being a d*** is a lifelong one’

The ‘Dawson’s Creek’ star is stepping into ‘the repulsive phase’ of his career, playing a real-life neurosurgeon who left behind a trail of damaged patients. He talks to Adam White about ageing, the toxicity of early fame, and his soul-searching about whether America is a fit place to bring up a biracial child

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A funny thing happens when you mention Joshua Jackson in conversation. Someone will inevitably let out a wistful sigh, a glimmer of recognition, even a mild squeal. It’s as if you can launch someone into a full-body flashback by mere mention of his name. Thanks to his Nineties roles – Dawson’s Creek, the Mighty Ducks movies, Cruel Intentions – he’s synonymous for a certain generation with first crushes and posters on bedroom walls; a living monument to early heart palpitations. Jackson gets it. He’s also sure he’s a terrible disappointment.

“I was downstairs at our hotel yesterday and getting the car to go out with the baby,” the actor says, handsomely. “And this young woman came up to me and she had just watched all six seasons of Dawson’s Creek. She’s like: I binged it, I loved it, thank you so much. But then I wondered: what is it like for you right now when I’m… grey? When I’ve got wrinkles and grey hair and I’m walking around with a baby? That’s got to feel weird, because literally days ago for you I was a pimply 22-year-old.” He shifts, winces a bit. “And now I’m very much not.”

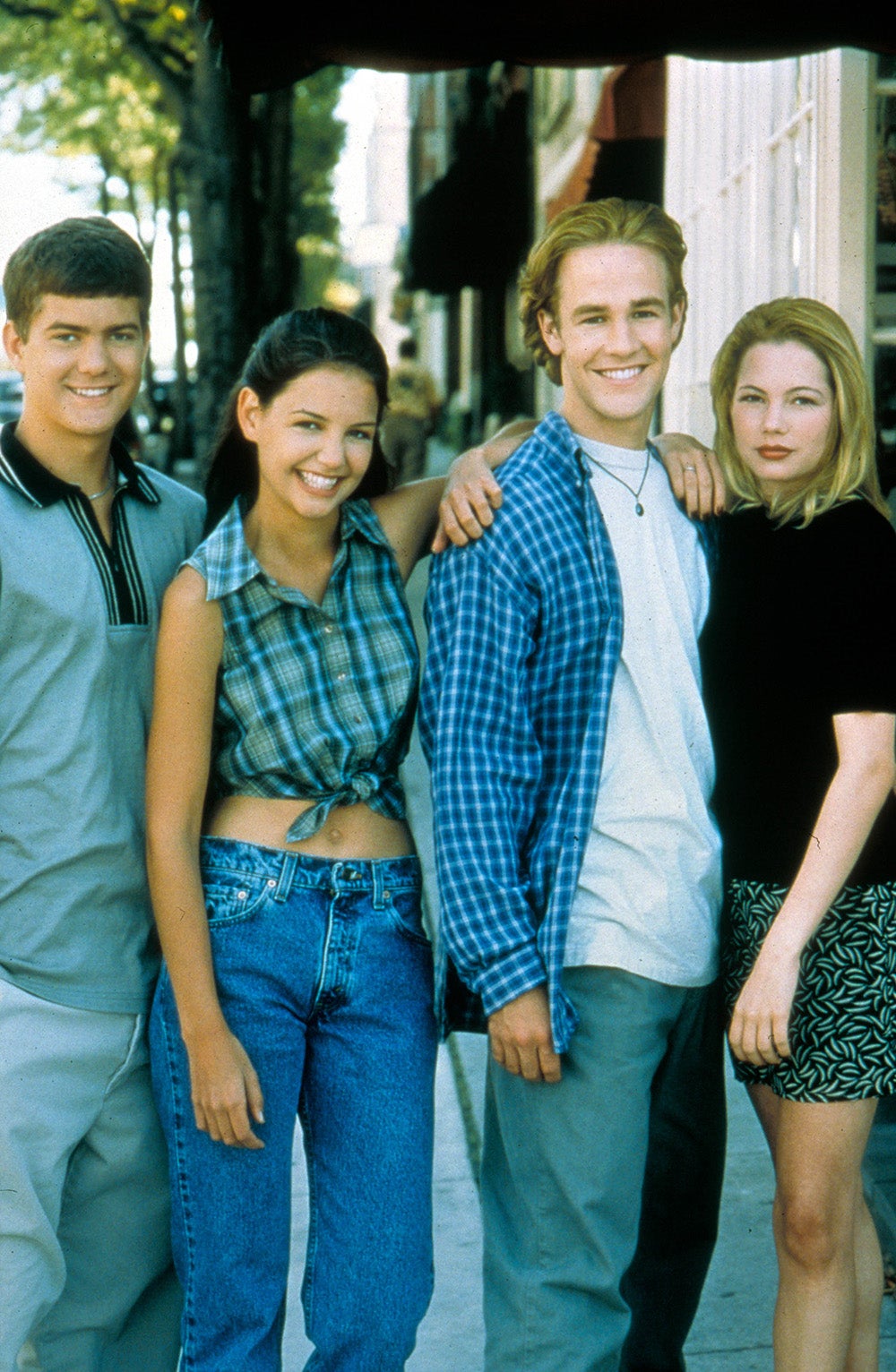

Jackson is being modest – he’s still almost supernaturally swoon-worthy – but he also has a bit of a point. He’s been around for what feels like forever, beloved from boyhood to young adulthood to a salt-and-pepper-bearded 43. He’s also bounced from hit TV show to hit TV show, Dawson’s Creek giving way to the cult sci-fi series Fringe, then the twisty melodrama The Affair and, last year, the socio-political soap Little Fires Everywhere with Reese Witherspoon. Jackson is very different in all of them – the rough-around-the-edges valour of Dawson’s Pacey Witter is worlds away from the exasperated, somewhat resentful Peter Bishop of Fringe – but an innate goodness always underpins his characters. Jackson can’t help it: he projects a charming affability as an actor; smooth, confident, almost Tom Hanksian in nature. So when he turns the goodness off, playing a murderous, narcissistic sociopath in his new limited series, it’s not just jarring, it’s practically a hate crime.

“I’d been looking to step into the repulsive phase of my career,” Jackson says with a deadpan that can only be described as Pacey-esque. He’s video-calling London from Cleveland, Ohio, where his wife Jodie Turner-Smith – the Peterborough-born star of Queen & Slim and Channel 5’s recent Anne Boleyn – is shooting a film with Adam Driver and Greta Gerwig. “So I’m here as the manny,” he says. Their daughter was born last year.

Jackson is also promoting Dr Death, a new eight-episode series available in the UK on STARZPLAY. He plays the real-life Christopher Duntsch, a debonair, Texas-based neurosurgeon who used his geniality as a smokescreen for medical ineptitude or, maybe, homicidal urges. The truth is unclear, but Duntsch inarguably left behind a trail of destruction: dead and maimed patients, colleagues baffled by his lack of surgical skill, and desperate fellow surgeons (played in the series by Alec Baldwin and Christian Slater) fighting shocking levels of bureaucracy just to get Duntsch’s medical licence taken away. It is a terrifying indictment of the US medical system and, considering the ease with which Duntsch breezed through life despite the dangers he posed, how much trust we put in educated, well-spoken white men with doctorates and charisma.

Jackson is brilliant in it, switching between compassionate self-assurance and the slippery volatility of Hannibal Lecter with ease. It’s a performance that creepily warps the actor’s natural magnetism and charm: Jackson using his superpowers not for good but for evil. Duntsch was a narcissist who thrived upon being the centre of attention, acting his way through life. Jackson has certainly spotted the similarities.

“I live and work inside of a very ego-driven business,” he says. “And a business where you fake it until you make it. You embody things that you don’t really have the experience of. What hopefully happens is, as an actor, at a certain point your empathy kicks in and you realise, ‘Oh, I’m being awful.’ And that was what was so compelling to me about playing this guy. He’s things that I have either been in dark times of my life, or seen in other people, but just pushed out to a place that I’ve never experienced before.”

Like what? “I understand when ego gets out in front of empathy,” he says. “I understand a problematic or complicated relationship with your father. I understand the desire to be seen as more than you see yourself.”

Jackson was born in Vancouver to an Irish mother, who worked as a casting agent, and an American father. His childhood was erratic – he moved to California for his father’s work, then back to Vancouver with his mother after his parents’ divorce, and struggled in school. “I also started to make money at a pretty early age,” he remembers, of local theatre in Vancouver, or small roles in Canadian independent films. “We weren’t destitute by any stretch, but there wasn’t a surplus of money to go around. And that can be an incredibly difficult, toxic place to navigate.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

He said that he used to overcompensate for his shyness by talking a lot and cracking jokes, though it often translated to speaking over those around him. It’s one of his regrets. “I think the process of not being a d*** is a lifelong one,” he jokes. “You have to constantly check in to make sure.” Today, he speaks eloquently and passionately, and is potentially the only man alive to successfully pull off wearing a signet ring on his pinky finger. He’s a more measured kind of gregarious, whereas the Dawson’s Creek era – he was 19 when the series began in 1998, and 24 when it ended in 2003 – found him struggling between two worlds: fame and adulation in one, and comfort and normality in another.

“Fame is notoriety, but it’s also access, and that can lead to some pretty dark places,” he says. “I was very lucky to have a life outside of my work that was in my hometown in Vancouver. It readjusted me very quickly into a social environment that not necessarily needed to knock me down a peg, but was willing to [both] celebrate my success, and tell me that I couldn’t get away with those more toxic traits.”

He alludes to at least a few years of excess. “A good friend will tell you when you’re being an asshole, or when you’re doing something wrong. Somebody who truly loves you will go through the discomfort of saying, ‘Look, man, this is terrible, you drink too much.’ I’ve had plenty of those conversations in my life. Like, ‘We’re not teenagers anymore. You’ve got to stop.’”

“Being Canadian is also a great antidote to the suck-up thing,” he explains. “When you start pushing out the peacock feathers, everybody’s gonna let you know who you are. I always find flattery deeply uncomfortable. Because I know my s*** does actually stink.”

Jackson refers to Canada often, joking at one point that he’s a Canuck right down to his marrow. It’s interesting, then, that so much of Jackson’s career has been rooted in the USA. Dawson’s Creek was earnest, homespun Americana, all row boats and abstinence. And Jackson’s most recent projects – Little Fires Everywhere, Ava DuVernay’s stirring, infuriating When They See Us, about the Central Park Five, and now Dr Death – feel like different kinds of American exposé, unearthing the rot beneath suburbia, the justice system and US healthcare. As someone from a different place, how does he see America?

“I’ve lived here for a long time, and the love I have for America is an immigrant’s love,” he says. “To me, an immigrant’s love is the clear-eyed love of a place that you’ve chosen to live. And what I think is fantastic about this country is its ability to grow. It is not yet an old country. It is not yet set in its ways. It is still sort of writing the story of what it is and what it can become, for better and worse.

The way America approaches and deals with Black bodies, particularly Black female bodies but Black bodies in general, is incredibly fraught

“To me, you can’t really get better at anything – as a country, as a person, as a couple, as a whatever – unless you can have a hard conversation, or actually look at the things about yourself that don’t work. I find myself drawn to stories that may seem like indictments, but I think are just honest conversations.”

He hesitates to say that he and Turner-Smith are settled in America, and admits that having a child has made them question where they ought to call home. “I’m learning a whole new raft of things,” he says. “Raising a biracial child inside of this country is difficult. The way that America approaches and deals with Black bodies, particularly Black female bodies but Black bodies in general, is incredibly fraught. So we have to make decisions about what will be the most nurturing psychological space for the baby to grow up in.” He sighs. “And we don’t know what the answer to that is.”

Before our time is up, I ask Jackson something that’s always nagged at me. For someone who is often the comic relief in things, or responsible for the levity in otherwise dramatic projects, how come he’s never been in anything out-and-out comic? He doesn’t get it either. He remembers shocking Reese Witherspoon on the set of Little Fires Everywhere when he told her he’d never made an actual comedy movie. And, no, their 1999 film Cruel Intentions – in which he played an outrageously camp pawn in a game of sordid prep-school blackmail – doesn’t count.

“Still to this day some of the best dialogue I have ever been given the opportunity to say,” he says, “but, you know, that’s a dark movie! He’s funny, what he’s saying is hysterical, but it’s dark. I don’t know why I always tend to end up in that place. So I need to get over myself and just have a laugh for once. It’d be a nice palate cleanser, just a straight romantic comedy.”

An entire generation will collapse into a puddle of nostalgic tears, of course, but it’d probably be worth it.

‘Dr Death’ premieres on 12 September on STARZPLAY

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments