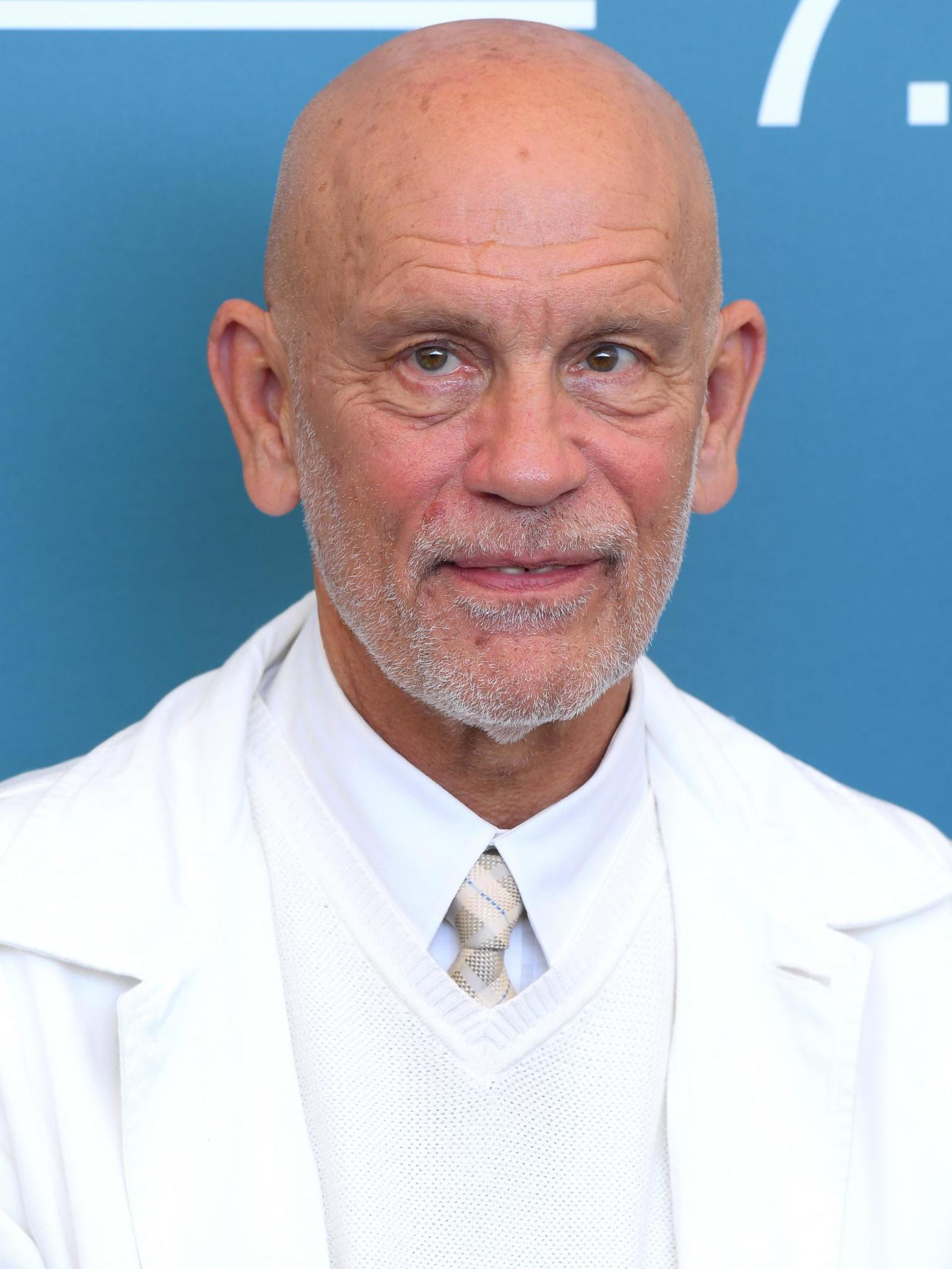

John Malkovich: ‘I get asked wild questions about my legacy. I’m an actor. My legacy is I’m a jerk-off’

The actor, fashion designer and winemaker talks to Phoebe Reilly about his new role as supreme pontiff in Sky and HBO’s ‘The New Pope’, as well as atheism and his infamous persona

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Oddballs, schemers and psychopaths: in the course of his long career, John Malkovich has convincingly played them all. But whether this makes him an unusual – or unusually perfect – choice for the role of supreme pontiff in HBO’s The New Pope is something he would rather not consider.

“I don’t think about how I’m perceived,” Malkovich says. “It’s not my business. You like Jackson Pollock? I’m good with The Night Watch. We all have preferences.”

Series creator Paolo Sorrentino (The Great Beauty), on the other hand, is unequivocal in his enthusiasm for Malkovich as Sir John Brannox, an English aristocrat and former punk musician who reluctantly takes over from Jude Law’s Pope Pius XIII when the show returns after a three-year hiatus on Sky Atlantic on 12 January.

“The pope is an iconic figure, and John Malkovich is one of the few iconic actors,” Sorrentino says. “How many actors can boast of their name being used in the title of a film?”

He’s referring to the 1999 movie Being John Malkovich, written by Charlie Kaufman and directed by Spike Jonze, which loosely capitalised on the mystique Malkovich had by then cultivated, mostly by way of his memorable villains in films like Dangerous Liaisons (1988), Con Air (1997) and In the Line of Fire (1993), for which he earned his second Oscar nomination.

When it came to imagining his series’ next pope, Sorrentino was similarly inspired by Malkovich, borrowing the actor’s slow, meditative diction and unnerving inscrutability as he shaped the character.

A troubled soul and fairweather friend to Meghan Markle, Brannox – who takes the name Pope John Paul III – leads the church warily compared with Law’s glowering and imperious Pius, who had a heart attack and slipped into a coma at the end of the show's first season, The Young Pope.

“John is elegant, suave and ironic, at once light and profound,” Sorrentino says of Malkovich. “He gives importance to things. But if those things didn’t exist, he could easily do without them.

“All these features seemed perfect for the character, so I stole them.”

As if in service to Sorrentino’s impression, Malkovich, 66, roams a suite at the Four Seasons in Beverly Hills on an uncommonly chilly December evening, fussing with the thermostat before giving up and rubbing his hands together for warmth. But unlike his pope, who mourns “the inexhaustible imperfection of the world”, he is unsentimental about his life’s work.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“You don’t really learn anything,” says Malkovich, who has appeared in more than 100 screen and theatrical productions, was a founding member of the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago and is also a vintner and men’s fashion designer. “You’re comprised of your experiences. And that’s what makes you, or in fact breaks us all in the end.”

His trademark gap-toothed smile spreads slowly across his face: “We die and then we’re gone. That’s OK.”

What did you and Paolo discuss in terms of how your character might be a different type of leader than Jude Law’s?

When we discussed it, mine was going to be a German who had spent a lot of time in England. Then he became an English aristocrat. The punk rock back story came when the decision was made to make him English. And then we communicated about what I thought was important, or what we could use more of or less of. But it wasn’t so much the discussion – the role kind of revealed itself in the writing and rewriting.

Of course with Paolo, most things are revealed when you see what the camera does. His way of putting people in a geography – in a room or outdoors, at a time of day – pretty much tells you what to do. The rituals, the secrets, the symbolism of the church: That’s a very hard kind of nut to crack with words.

Did putting on the papal vestments prompt something more in terms of connecting to that character?

Yeah, sure. Because the church just fits into all those S’s: symbolism, spirituality, sacredness, secrets. It satisfies a longing that I think naturally exists in people. How do we live? Why are we here? Was I even here? We kind of forget to ask those questions. That’s what I think the church is for. You know, I’m an atheist but I get the point. And that’s something I think Paolo, being Italian and being Catholic, just understands on the most profound levels.

We are rich in pontiff-related art right now, between The New Pope and the new Netflix film The Two Popes. Why do you think this subject compels us?

Well, I haven’t seen the one with Jonathan Pryce and Anthony Hopkins (The Two Popes), but I think it probably came about due to the fact that there are actually two living popes – that’s a pretty unique thing happening in a religion with a billion-plus adherents. And the attention isn’t that surprising at a time when people maybe are searching for something, some spiritual element, to their existence. Even though the world is wildly more secular than it was 20 years ago, let alone 50 or 100 years ago, the pope is a kind of father and mother that a huge number of people look to for guidance.

Were you raised in a religious household, and was there a moment when you broke with faith?

No. My parents were sort of evangelical atheists. I was religious when I was young, quite possibly in reaction. Just over time, I didn’t believe. I don’t make snarky remarks about it. I’m happy to be in a church or a temple or a mosque. I just don’t see that there’s some plan. But who am I? I’m nothing. That’s just my own feeling.

It was reported that, when you were filming in Rome, bystanders handed you their babies to be blessed. Why do you think they did this?

I don’t know. There exists this notion that we can be blessed into a state of grace. Maybe somebody can do that. Not me, certainly. I mean, if you give me a baby, I’ll keep it unless you want it back. I love babies. I’m always detached from, but amused by, the confusion people have between one’s characters and oneself.

Like Being John Malkovich, The New Pope breaks the fourth wall when a character remarks on your character’s resemblance to the actor John Malkovich. What do you think it is about you that invites this playfulness with your persona?

It sort of seems like my life’s goal is to promote references to myself. But it’s actually not. I think it’s not related to me. People sometimes ask me these wild questions about my legacy. What are you talking about? I’m an actor. My legacy is I’m a jerk-off.

Still, Being John Malkovich must have a certain pride of place for you, either on your résumé or in your heart.

Having a film called Being John Malkovich doesn’t really mean much to me. Having had a half-percent part at the inception of Spike Jonze’s and Charlie Kaufman’s careers means much more. I’m happy about that because they made something that was well out of the norm, broke many rules and introduced two very big talents. People forget I’m just an actor in it. I had nothing to do with the conception. I didn’t write a word. When I first read it, I wanted to direct it. I wanted the focus to be, say, William Hurt or Tom Cruise or William Shatner or whoever. But Charlie had no interest in that.

You share a scene in The New Pope with Marilyn Manson. Was he what you expected?

He’s quite church-like. His show... there’s a lot of pageantry and a lot of play with the sacred, or not-so-sacred. I don’t know his work that much, but I loved doing the scene with him. I think he’s very clever, very funny, very easy to talk to.

You’re a winemaker and he makes absinthe. Did you exchange bottles?

I don’t think he talked about that. I’ll have to ask. I think my daughter likes absinthe.

Did you have any hesitation about stepping into the role of a hallowed figure, or sense any resistance from believers to the scandalising aspects of the series?

I don’t know how the believers regard it, although I’d be interested to hear. I didn’t really talk to any Vatican figures, but I mean... Jude Law playing the pope? I think it’s safe to assume that viewership at the Vatican was pretty high. A lot of people like to watch things about their world and what they do.

Has playing the pope and also a Harvey Weinstein-type figure in David Mamet’s recent play Bitter Wheat led you to any new insights about men in power?

A few years ago, I was touring in an opera-hybrid theatre thingy in Europe, Just Call Me God. I played a Saddam Hussein-like figure, but a line I wrote in that was “the one thing I know about power is the good never seek it”. And that’s not wholly inaccurate.

You wrote and starred in a film directed by Robert Rodriguez called 100 Years, which won’t be released until 2115. What drew you to that idea?

It’s a commercial thing for the Remy Martin company. They explained to me that their premium cognac, Louis XIII, takes 100 years to make. So the steward of it never sees it, and neither does the one after that. And I thought it was kind of a fascinating thing. Perhaps my children, if they have children, those children could be alive when the film is released. Probably more likely their grandchildren. In a way, what Robert and I did was a letter from the dead. That’s quite satisfying.

© The New York Times

The New Pope is on Sky Atlantic from 12 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments