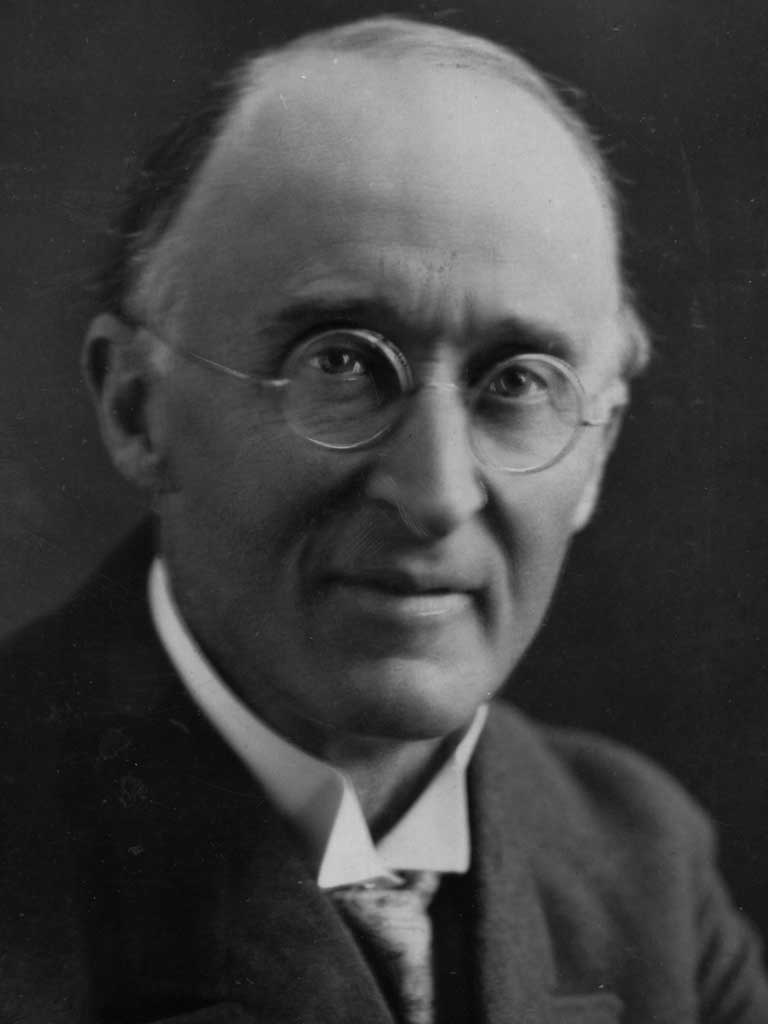

Frederick Delius: How a great British musical myth was born

A BBC film will shed light on the enigma of Frederick Delius

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Image management isn't such a recent phenomenon after all. In John Bridcut's new documentary about Frederick Delius, marking the 150th anniversary of his birth, an extraordinary history emerges, revealing the degree to which the composer's chief champion manipulated his reputation to make him appear more "British" than he really was. That champion was none other than the celebrated conductor Sir Thomas Beecham.

His interference went well beyond the call of duty. A year after Delius died, Beecham had his body disinterred from its French grave and reburied in a country churchyard in Surrey. So controversial was this that the service was held at midnight to keep the press away.

Without Beecham's advocacy, Delius could have been forgotten altogether, so rarely was his music heard. "In a sense, Beecham felt Delius was his property," Bridcut says. "Because he was British, he felt there was real value in labelling Delius as British too. When Beecham took Delius up, the only country that was really performing his music was Germany. I suspect that the whole thing became polarised because of First World War. In fact, Delius wrote scarcely a note of music in England, and the fact that he spent the first 22 years of his life in Bradford was almost incidental."

Beecham's touch extended to the music itself. Delius was unaccustomed to preparing his works for performance and tended to leave out crucial instructions about expression and dynamics. Beecham added his own, admittedly for practical reasons; they are used to this day. In Bridcut's film, though, the conductor Sir Mark Elder explains what happened when he scrubbed out Beecham's markings in Delius's Walt Whitman setting, Sea Drift. Without them, he says, the seascape sounds calmer, with a less exaggerated sense of swell: "You can almost see the light on the water," he comments.

It makes sense: this composer was a sensualist for whom beauty of sound became an end in itself. As another keen Delius conductor, Sir Andrew Davis, points out in the film, we tend to expect music to develop, to "go somewhere". Instead, he says, Delius's music can "just sit there and be beautiful". Perhaps that is why it still polarises opinion. "It's musical Marmite," suggests Bridcut.

Little love was lost between Delius and his native UK, let alone his parents, who virulently disapproved of his musical vocation. The family was German and had a business in the wool trade, which led them to settle in the North of England. Fritz – his real name, which he changed to "Frederick" after his father's death – escaped to Florida aged 22, ostensibly to manage an orange plantation. The spirituals and folk singing he heard there left a profound impression on his works.

Later, he migrated to Paris, where he moved among writers and artists in intellectual and bohemian circles. He bought a masterpiece by his close friend Paul Gauguin: the famous Nevermore. But his hedonistic lifestyle had severe consequences: he contracted syphilis, which later left him paralysed and blind. His wife, Jelka, supported him both morally and financially. When times grew hard, the Gauguin was sold. Delius never lived in Britain again.

Delius's widespread image – essentially, Max Adrian in Ken Russell's film Song of Summer – has done little to convey the full picture of the composer as the passionate libertine that he was; the exotic musical equivalent, perhaps, of Gauguin himself. In this anniversary year, with performances aplenty at the Proms, Bridcut's film is the perfect place to start exploring his life and work afresh.

'Delius: Composer, Lover, Enigma' is on 25 May at 7.30pm on BBC4

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments