‘Sometimes you take a mean character home – until your partner tells you to knock it off’: Bryan Cranston on Walter White, Your Honor and making Jerry Seinfeld laugh

The Oscar nominee tells Annabel Nugent about landing his breakout role, aged 44, in ‘Malcolm in the Middle’, and finding his way out of his toughest characters

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Bryan Cranston is showing me his Breaking Bad tattoo. Asking an actor about their most famous role can be risky – especially if that role is a decade old, and in that decade they’ve gone on to earn Tony awards, Oscar nods, and do any number of interesting things. Cranston is happy to oblige, though. Thrilled even. “Here it is!” He splays out his fingers so they straddle the camera. On the inside of his ring finger is the tattoo he got on his last day filming the 16-time Emmy-winning series that changed his life. The ink is faded now and the letters bleed into one another, but the symbols are instantly recognisable: Br. Ba.

“This will be 10 years old in another month,” sighs Cranston. He hikes up his eyebrows as if to say, Can you believe it? Cranston is that rare ageless actor, seemingly born into middle age and never growing a day older. He was 44 when he landed his breakout role as Hal, the hapless patriarch of Malcolm in the Middle; 52 when he began his tenure as the nebbishy chemistry professor turned grizzled drug lord of Breaking Bad; 58 when he won a Tony for his jet-fuelled performance as US president LBJ in All the Way; 59 when he got an Oscar nomination for portraying the screenwriter of the title in Trumbo; and 61 when he played a news anchor on the edge in the stage adaptation of Network. He won a second Tony for that. But, at 66, he still looks like Hal. In a rapidly changing industry, Cranston’s forehead creases are a comforting constant. His transformation in Your Honor, then, comes as a shock. For the first time ever, he looks old.

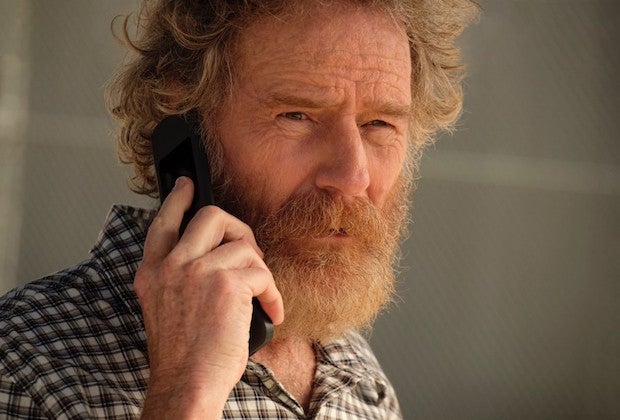

The series, which returned for its second season this month on Paramount Plus, sees Cranston as Michael Desiato, a morally upright New Orleans judge. The halo slips, however, when his son kills the son of a crime boss in a hit-and-run. Michael covers it up; chaos ensues. After the staggering denouement of series one, Michael is a man transformed. Physically, too. Cranston lost 16lb for the part. “I wanted my ribs to be very apparent,” he says. “I wanted people to go, ‘Oh my God, he’s very thin.’ This is a man who has lost everything.” Early on, we see Michael undressed, wearing only an unruly beard and his underwear. He’s hunched over and scrawny. “It was tough. You see these big, delicious bowls of pasta that you can’t have. I’m always surprised when people ask how I gained the weight back. I’m thinking, how did I lose it?” says Cranston, clean-shaven now. “My beard was big and bushy. It grew wherever it wanted to, so there was freedom in that, but the discipline came in the weight loss.”

Passing on pasta is worth it for Cranston, though. “Any time you can look in a mirror and believe what you’re seeing, it helps tremendously,” he says. “For actors, every time we start a new project, the character is outside of ourselves. It’s out there somewhere.” It’s an actor’s job, then, to bring it closer. You put in the work until suddenly – “slurp!” – the character is inside you. “It’s almost like osmosis,” he explains, “and then once you have it inside, you think, thank God, it’s there.” He grasps at his chest as if trying to keep something in.

Cranston often speaks like this, in earnest and in second person – not to deflect, which is its typical purpose, but to instruct. Ask him anything and he’ll find a way of steering the conversation back to his favourite subject: acting. So intensely and meticulously does he talk about the craft, in fact, that you suspect he would make a fantastic film professor. He lets me in on the four-step guide to becoming a good actor: talent (“it can’t be taught but it can be nurtured”); an insatiable curiosity (“a willingness to read and read and read”); a treasure chest of your personal experiences (“not just joy but also despair; here’s pain, here’s anger, here’s vengeance, all those ugly things”); and lastly, a keen imagination to connect the pieces. “You put it all together, and those are the tools to create an interesting, compelling character.” I feel like I owe him a tuition fee.

His career is the culmination of hard work, talent, risky choices, and luck. He puts strong emphasis on the latter. Cranston says success came early for him. It’s a surprising declaration; here is an actor who was in his mid-forties when he broke through. But recognition was never the goal: Cranston wanted to support himself. Everything else was a bonus. “When I started my career at 23 years old, all I really wanted to do was be able to make a living,” he says. “Make my living as an actor – that was my measure of success, and I achieved that just two years later at age 25. All I’ve done for a living since is act. I can’t think of a more blessed experience. How lucky I am.”

Luck has something to do with it, sure, but Cranston works hard. He plugged away as a guest star on shows such as Chips, Airwolf, Baywatch and Murder, She Wrote for more than a decade before he landed his role on Malcolm. Among those guest appearances was a five-episode stint on Seinfeld in the Nineties. Starring in the sitcom was like “comedy bootcamp”, says Cranston, who played Tim Whatley, dentist to the stars. “Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David are like skilled surgeons with comedy. They’ll slice something up, remove a moment, or include a moment.” One time, the pair suggested that Cranston wait two seconds before delivering a line. “They said it would get a bigger laugh that way.” Their advice worked. “It’s a very delicate, very perishable thing, comedy.” Cranston was no slouch himself. He elicited plenty of laughs, often to the detriment of filming. “Every time we had to stop taping, it was because Jerry was cracking up,” recalls Cranston. “And if you can make Jerry laugh, you’ve really hit a home run. Right after, I got Malcolm in the Middle; my experience on Seinfeld helped me get ready for that.”

Cranston grew up in Canoga Park, Los Angeles, the middle sibling of three. As a child, he was obsessed with baseball. Still is. “My bedroom had a lot of baseball paraphernalia.” Hats and trophies from competitions he participated in growing up. (He’s an LA Dodgers fan; “Win or lose, you’re always riding the wave.”) His parents, who met in acting class, separated when he was 12. Cranston has previously talked of how an unfulfilled dream to become a star destroyed his father. “It went past believing in yourself. My belief in myself was the hope that I could earn a living in this business,” he says. ‘My dad had a different approach; he was looking for results, and it affected him in a negative way for the rest of his life. So I learnt from him, unfortunately, what not to do. Not to look at it and say, ‘I want to be a star.’”

Cranston had enjoyed performing from a young age, but witnessing his father’s troubles very nearly put him off the idea altogether. “I realised, ‘Whoa, maybe this is not the thing for me to do,’” he says. He decided to pursue his other talent: police work. Maybe it would be cool to be a detective, he thought. Cranston studied police science at college but continued to pursue acting as a hobby. In his second year, he took an elective acting class, where he met a girl. A really pretty girl. “It’s my first day and I’m nervous,” he recalls. “I’m looking around, and I’m sitting next to this girl, and I look down at the script and it says, ‘A couple is making out.’” His eyes widen, his mouth is agape. “Just think... you’re a 19-year-old boy, and your job is to make out with a really pretty girl. That’s the job effectively. Your head explodes. That’s when everything spun around: wow, this is so much more fun than police science. You’re never supposed to kiss a girl in police science.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

And so, Cranston gave in to the acting bug. With some asterisks. “You can go into the same business [as your parents] but have ideas of how you’d make adjustments and how you would approach certain things. And that’s what you do.” His parents were actors; his grandfather was an actor. “I went into the family business. When my daughter decided to become an actor, that’s fourth generation. She’s in the family business, which is very common.” Taylor Dearden, who has appeared in Sweet/Vicious and Netflix’s American Vandal, was not featured in New York magazine’s investigation into nepotism babies – but, as the daughter of Cranston and fellow actor Robin Dearden, his wife of 33 years, she could have been.

It was seven years of glory. Going to work every day and making yourself and others laugh. That was my job

After a string of guest appearances, Cranston finally got his toehold in the industry with Malcolm in the Middle. The Fox sitcom ran for six years and won seven Emmys. Starring opposite seven-time Emmy nominee Jane Kaczmarek (“My beloved Lois!”), he made his name on screen as Hal. The role was a showcase for Cranston’s physicality, especially the way he can transform his face from putty to steel in an instant.

No doubt Cranston turned in a great performance as Hal, but he came with great ideas, too. Crucial ideas, in fact, that made his character – whom the creator admitted was initially underwritten – so pivotal to Malcolm’s success. It was his pitch, for example, for Hal and Lois to be happily married. Truly happily married. Their relationship is a port in the storm of family dysfunction on screen. “I said, what if this relationship was really good? What if he just cherished his wife? And so the writers went with that. To Hal, Lois could do no wrong. He just swooned whenever he was around her.” Cranston laughs. “Of course, that’s why they had five kids.”

At a time when anything and everything is being rebooted, the idea of a Malcolm in the Middle movie has been floated. Cranston is optimistic. “It’s a possibility,” he says. Months ago, he brought it up with the show’s creator, Linwood Boomer. “He said he would think about it, and he got his writers together. If they can come up with a great idea, a legitimate idea, then he’ll pursue it. But if not, then nah. I don’t need a job. I’ve got plenty of jobs. I don’t need it, but I’d want it if it was a great idea.” Over time, the legacy of many a nostalgic comedy show has become tainted by reports of on-set feuds and bad behaviour. Malcolm, however, remains pure. “It was seven years of glory,” grins Cranston. “Going to work every day and making yourself and others laugh. That was my job.” It’s like getting to kiss that really pretty girl all those years ago, he says.

After Malcolm ended in 2006, Cranston seemed destined to play the Hal type for ever. He escaped this fate largely thanks to TV writer Vince Gilligan, whom he’d worked with on a 1998 episode of The X Files. Gilligan wanted Cranston to be the star of this new show he was working on called Breaking Bad, about a chemistry teacher who starts making meth. By then, though, millions recognised Cranston as a goofball father of five. Casting the dad from Malcolm in the Middle as a meth magnate was a hard sell. But it paid off – and then some. It was only a matter of months between the end of Malcolm and the beginning of Breaking Bad, but the gear-change was so extreme that it felt like a second act in his career.

For five years, from 2008 to 2013, Cranston poured himself into the role of Walter White, as the character’s moral compass slowly but surely crumbled. The transformation was so jarring that Anna Gunn, who played Walt’s wife, told The New Yorker she felt genuinely “alone and scared and angry” whenever Cranston’s character turned on her during scenes. A number of co-stars can attest to those same feelings. But Cranston isn’t a Method actor – for all his sincerity when speaking about his craft, he makes it clear that it is also just that. His craft. Not his life. As important as it is for him to be able to delve into that trove of experience and pull out pain and cruelty, it’s equally important that he can find his way out again.

Cranston compares it to rolling out your mat before yoga. “Your body knows what you’re about to do,” he says. “It’s the same thing for an actor. When I go to work, my body knows where we’re going, and it knows how to get there, and then you flip that switch and cleanse yourself of the toxicity of those emotions you don’t want to carry into your regular life.” Actors aren’t born knowing how to use the switch. It’s a skill, and like any skill, it must be practised. “It’s definitely something you have to learn at first,” says Cranston. “Sometimes you’re playing a mean character and you take it home with you – until hopefully your partner tells you to knock it off.” The switch is about self-preservation – especially if you’re attracted to darker roles, as Cranston evidently is. “You need it to live a normal life,” he explains. “I don’t want to live in the characters I play. I would be completely exhausted if I had to take them home with me.”

Home is a special place for Cranston. A space of security and stability that exists in direct contradiction to his job. “Acting feels tentative,” he says. “It doesn’t feel like it’s foundationally structured to last long.” The number one thing, he explains, is to “make sure your personal life is as sane and as structured as possible. If you have that, then in your creative life you can go anywhere, because there is this invisible tether back down to sanity.”

Cranston recalls an evening at an awards show some years ago. He was wearing a tuxedo; his wife was in a beautiful gown. Photographers and fans were shouting his name. Hours later, he gets home, pays the babysitter and takes the rubbish out, trying desperately not to get the bin juice on his patent leather shoes. “I smiled, because that’s the way life should be. Sometimes people want your picture,” he says, laughing. “Other times you’re taking out the rubbish.”

‘Your Honor’ season two is streaming now on Paramount Plus

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments