Are we witnessing the death of ‘distinctive’ British TV?

ITV had a huge hit with the powerful real-life drama ‘Mr Bates vs The Post Office’ back in January, but the broadcaster believes that it’s getting harder and harder to make ‘very distinctively British’ shows. Katie Rosseinsky explores why series like this might be a dying breed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Cast your minds back to the very start of the year and you might remember how one show dominated the national conversation. Mr Bates vs The Post Office was a hard-hitting dramatisation of the Horizon scandal, a miscarriage of justice that saw hundreds of subpostmasters wrongly prosecuted for theft. The four-part ITV series had an immediately galvanising effect. A petition calling for the victims to be better compensated gained hundreds of thousands of signatures. The government put forward new legislation to exonerate them. Later, former Post Office CEO Paula Vennells handed back her CBE. Mr Bates was lauded as a shining example of TV’s power to change the narrative off-screen. It also became ITV’s most-viewed drama in over a decade, beating Downton Abbey’s 2010 launch; to date, 13.5 million people have watched it.

All in all, a runaway success, right? Beyond the critical acclaim, the news stories and the viewing figures, the reality is a bit more complicated. The channel in fact lost around £1m on the series – in no small part down to the fact that it was a tough sell to foreign broadcasters. Earlier this week, ITV told the culture, media and sport select committee that “rising costs and stagnating commissioning budgets mean that margins for very distinctively British content are narrowing”, all at the very same time that “international customers want content that travels well globally”. The UK has a strong history of powerful and purposeful dramas shining light on social issues: from Jimmy McGovern’s Hillsborough, which dramatised the fight for justice for the victims of the football stadium disaster, to more recent series like It’s A Sin, exploring the impact of the Aids crisis, and Time, another McGovern show, this time highlighting our broken prison system. So could programmes like these soon become a thing of the past?

Answering that question requires digging into the perfect storm that has hit the UK’s much-vaunted entertainment production industry. Just a few years ago, the market was booming, with streamers flocking to the UK to make films and high-end TV series, taking advantage of skilled crews, great VFX facilities and generous tax credits. Demand for crew was so high in this country that anecdotes of British workers jumping ship to other, better-paid streaming projects in the middle of a shoot became commonplace. In 2022, the combined production spending for film and high-end TV – defined as a series that costs more than £1m per episode – reached a staggering £6.27bn in the UK, the highest amount on record. Eighty-six per cent came from foreign investment. The sector was, it seemed, one of few to bounce back stronger than ever in the wake of the pandemic.

Since then, though, there has been a major plot twist: the industry’s fortunes have taken a sharp turn for the worse in the UK. There’s not one standout villain to blame, just a combination of difficult circumstances, many of which are impacting the global industry more broadly, too. The cost of living crisis (including skyrocketing energy bills) has ramped up production costs for film and TV makers everywhere. Fears about cash-strapped audiences cutting back on streaming subscriptions spooked Wall Street last year, prompting budget cuts and show cancellations at many of the big US entertainment companies (the very same companies that were driving the UK production boom). And then there was a historic double whammy: a Hollywood writers’ strike was followed by similar industrial action from members of the acting union, Sag-Aftra, prompting filming to come to a halt around the world.

On this side of the Atlantic, there have been some UK-specific issues to contend with. The BBC license fee was frozen between 2022 and 2024; and the broadcaster has claimed that the recent below-inflation increase means that “our content budgets are now impacted, which in turn will have a significant impact on the wider creative sector across the UK”. Last year, Channel 4’s commissioning slowdown made headlines. Plus, TV ad spend is currently in the doldrums (in part thanks to our diffuse viewing habits) meaning even less money to spend on new programmes. Late last year, Channel 4’s chief executive Alex Mahon said that “this level of advertising fall has only been deeper during the 2008 recession”. It’s the industry’s majority freelance workers who are really feeling the pinch. When Bectu, the union for the entertainment and media industry, surveyed its members in February, they found that 68 per cent of film and TV workers were not currently employed, marking only a 7 per cent improvement since September last year (when the actors’ strike was still in full swing). Eighty-eight per cent were concerned about their financial security over the next six months.

This depressing picture leaves British television increasingly reliant on those all-important international sales (or, in some cases, co-productions with foreign broadcasters to share the costs). But when those international companies are also struggling with budget cuts, it’s tough to tempt them with a very British story full of local quirks and character actors. “It is harder and harder to make the economics work in a way that is less true of dramas with obvious global appeal,” ITV has said.

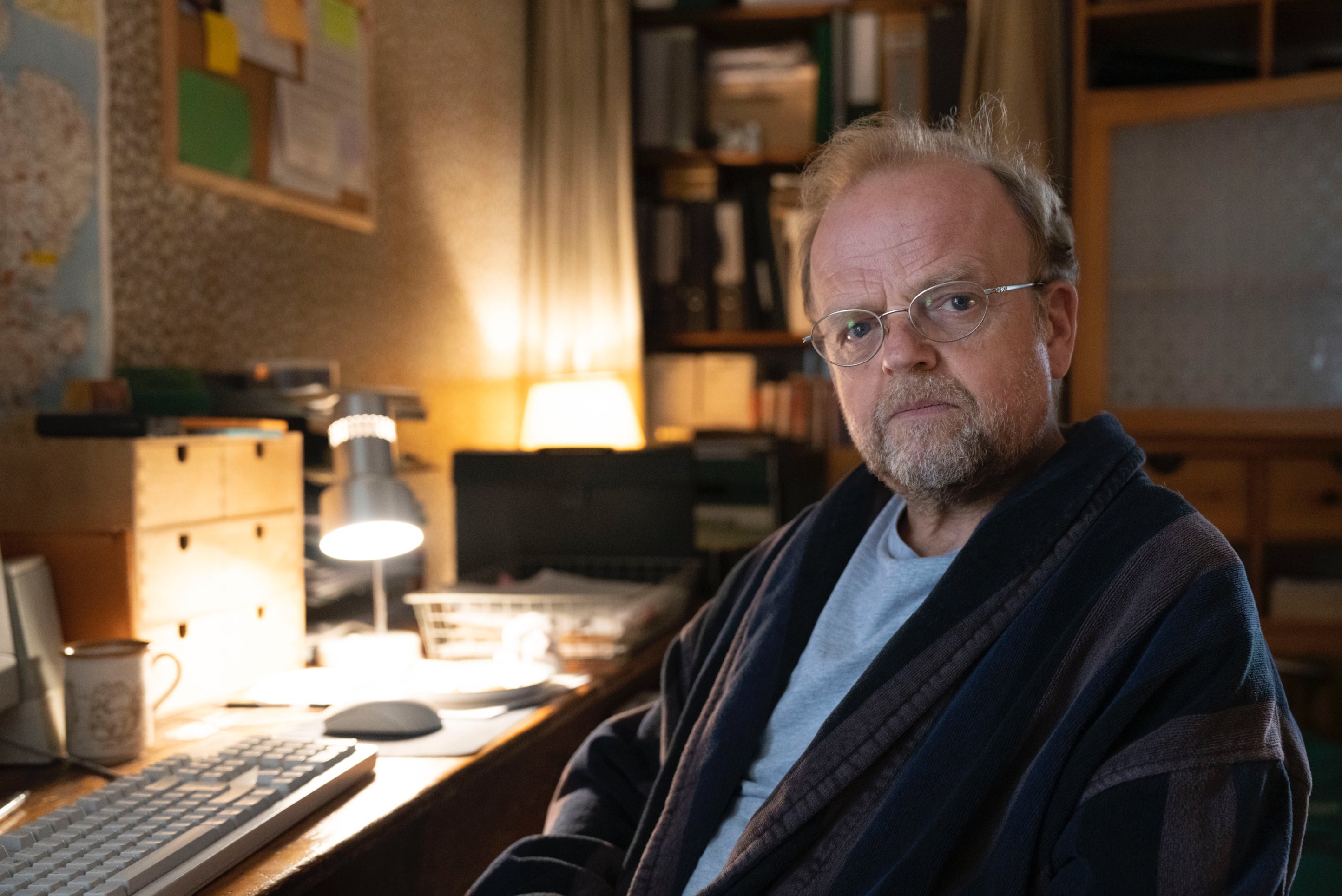

In this tough landscape, it’s clear to easy why a broadcaster might shy away from a “niche” UK story that doesn’t easily fit into a sellable genre (unlike, say, a thriller such as the London-set Bodyguard, the broad strokes of which would probably work if they were transplanted onto a different backdrop). Take Mr Bates. As ITV’s head of media and entertainment, Kevin Lygo, bluntly put it: “If you’re in Lithuania, four hours on the British Post Office? Not really, thank you very much.” BBC prison drama Time and The Sixth Commandment, a sensitive dramatisation of the Maids Moreton murder case that recently earned lead actor Timothy Spall a Bafta, are among the best, most moving shows of recent years. Yet they feel quite anomalous in their nuanced depictions of specifically British stories; it is hard to imagine them being as well-watched elsewhere.

It is harder and harder to make the economics work in a way that is less true of dramas with obvious global appeal

It seems like the tricky current market might be accelerating the homogenisation of telly, a process that’s arguably been in the works since the streaming boom kicked off. You’ve probably seen its uncanny effect: where a show ostensibly takes place in a specific location, but the characters and setting feel strangely unspecific. Think of Harlan Coben’s thrillers on Netflix, filmed in the northwest of England but dissonantly American in their overall feel. Or Sex Education, where the high school in question looks more Glee than Grange Hill.

Of course, the idea of “distinctively British” TV is a contested one (and can be used as a distracting political football). In 2021, Tory minister John Whittingdale announced his intention to compel public service broadcasters to produce a certain amount of “distinctively British content”, citing shows like Downton Abbey, The Great British Bake Off, Only Fools and Horses and Fleabag. It’s safe to say his plans didn’t go down too well. Many noted that the examples weren’t entirely representative of our national culture – and that the industry already had a problem with only platforming certain stories and certain behind-the-scenes creators too. It also didn’t help that Whittingdale included Derry Girls, a show set against the backdrop of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. There are scores of other TV productions from recent years that didn’t make it to the minister’s narrow list, but are still testament to the power and breadth of British creativity: I May Destroy You, Happy Valley, Steve McQueen’s Small Axe … hell, even Love Island in its heyday. Beyond those culture wars, though, it would be a real shame to see British shows losing their distinctive character – and not just because it could stop important stories like Mr Bates from reaching a mass audience.

An emphasis on “global appeal” might stymie the work of screenwriters new and experienced, forcing it to fit into a tidy, marketable mould. That feels pretty short-sighted, as it’s often the “niche” series that give great talents space to breathe. Jesse Armstrong, showrunner of HBO’s Emmy-winning critical smash Succession, got his start on Peep Show, a show that would only have been commissioned by Channel 4 (and one that, I’d argue, gets right to the heart of a certain “distinctive” British male psyche).

ITV have said they commissioned Mr Bates knowing that it would be a hard sell, because they “felt the responsibility to tell the postmasters story was important”. They clearly made the right choice – it’s hard to put a price on the show’s impact. But for how much longer will our broadcasters be able to make these gambles?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments