Blitz: The bombs that changed Britain

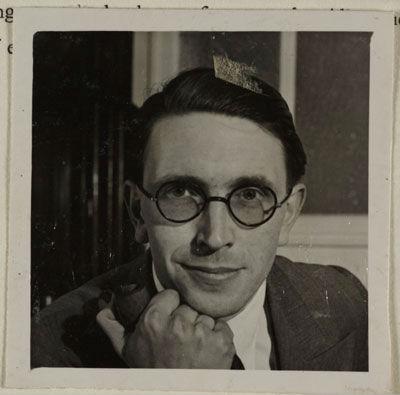

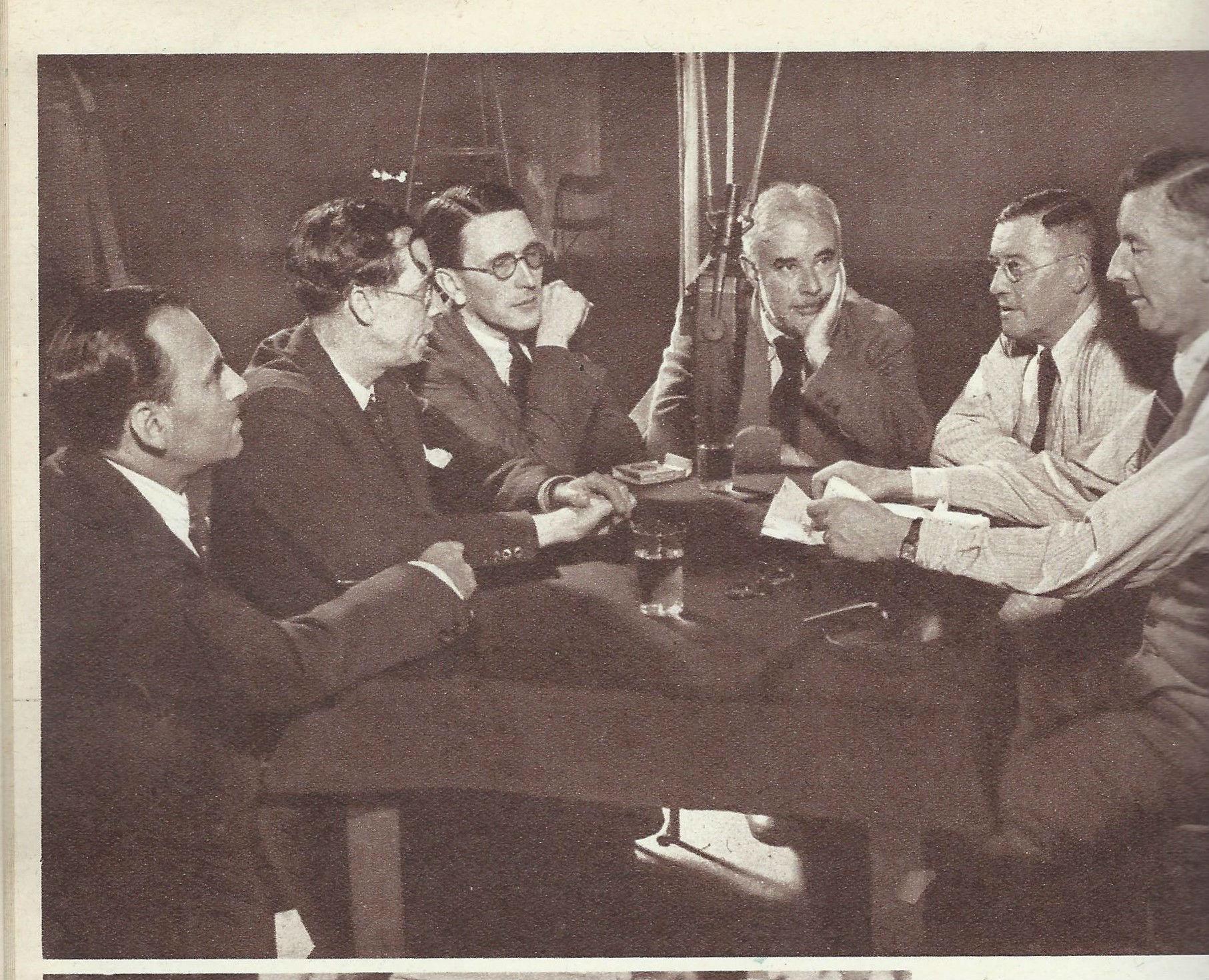

As a new BBC series shows how the welfare state was built on the devastation in London's East End, The Independent’s Simon Calder reveals the story of his journalist grandfather Ritchie, who saw the destruction first-hand

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As with 9/11, so with the start of the Blitz. On a God-given September day with gentle sun shining through a crystal-clear sky, unimaginable violence ensued.

On that bright Saturday, 7 September 1940, the “Lightning War” began. Wave after wave of Luftwaffe bombers flew in over the North Sea and Essex. They swooped down over east London to unleash their deadly cargo on the docks, where much of the Second World War logistic effort was concentrated.

Besides ships and supplies, London’s Docklands was home to hundreds of thousands of people who kept the Empire’s lifeblood pumping. Their terraced homes were often only yards from the quaysides. On “Black Saturday”, as it came to be known, East Enders found themselves living beneath the bombsights of Dornier, Heinkel and Junkers aircraft.

Nazi Germany kept up the murderous assault through the night. Just before 6am on Sunday, a bomb fell through the roof of 8 Martindale Road in Canning Town. It failed to explode. But this single impotent bomb signalled hideous potential threat to Dockland communities. As the BBC Two documentary shows with first-hand testimony, news cuttings and some meticulously kept official records, tragedy was soon to follow.

As the dust settled on Canning Town that Sunday morning, my grandfather, Ritchie Calder, took a taxi to the scene to survey the damage of the opening gambit of the Blitz. He was a 34-year-old journalist for the left-wing Daily Herald. What he discovered horrified him: shocking disorganisation, compounded by official lethargy.

“Many services and preparations which could have been foreseen had to be hastily improvised while bombs were dropping and people were suffering,” he wrote.

Many residents survived the air raids, but had their homes destroyed. 8 Martindale Road became the location for a terrifying amount of high explosive.

The displaced occupants became, in official parlance, refugees. But rather than being evacuated from the danger zone, they were taken no further than South Hallsville School – a few streets away – in the middle of the area taking the brunt of the bombing.

In the early hours of Tuesday morning, 10 September, what Ritchie Calder described as a “calculable certainty” came to pass.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“Major occurrence 0349 West Ham at South Hallsville School,” read the first despatch. “Badly damaged. 600 refugees accommodated here. Stated to be in panic. Casualties unknown.”

The next despatch attempted to put the first figure on that “unknown”; “at least 200, mainly children”, it mourned. A message sent by rescue workers on the scene was blunt: “Cancel the buses. Send us morgue vans and ambulances.”

Ritchie Calder had grown up in a world at war. He was eight when the Great War began, 12 when it ended, and 33 when the Second World War started.

“Goering’s arson-squadrons,” as he described the Luftwaffe raids, moved the front line to the cities of a nation that was pitifully unready for the onslaught.

The authorities had prepared for the wrong war. They anticipated that chemical weapons would be unleashed on civilians. But Hitler’s preferred weapons of mass destruction relied upon the brute force of high explosives and incendiary bombs.

As politicians dithered, officialdom only intensified the suffering of survivors who had lost everything.

Each refugee, always desperate and often bereaved, faced a battle with bureaucracy. They had to navigate through a tangle of red tape that must have seemed impenetrable, visiting a succession of offices in order to procure everything from new identity cards to Government-issue clothing.

Ritchie Calder paced out the painful journey that the destitute had to make, and recorded the walking distance as eight-and-a-half miles.

He was an avowed patriot – though some disputed his profound belief in Britain as he raged against the system.

“It has been my job to expose the faults and to discover the remedy, and in that capacity I have been a constant and often violent critic,” he later wrote.

Remarkably, amid the chaos of a war that Britain was in very serious danger of losing, the establishment began to forge a decent, humane social policy that treated the common man and woman with the dignity they deserved.

The government, shamed into fresh thinking, began to create the foundations of a Welfare State on the rubble of East End terraces. Soon, bombed-out civilians were able to start reassembling their lives at hurriedly established bureaux which we would now see as one-stop shops.

By the time the military tide had turned and it seemed that liberty would prevail, plans for a National Health Service had emerged.

By then, Ritchie Calder had been recruited for the war effort. In recognition of his writing skills, he was invited to head the Political Warfare Executive. He wrote Carry on London (a morale-boosting book, not a comedy film) and delivered compelling messages to the Home Front, the armed forces serving abroad, and the enemy – who promptly responded by bombing the Calder family home.

But no one knew better than Ritchie how to start again.

‘Blitz: The Bombs That Changed Britain’ is a four-part series that begins on BBC2 at 9pm on Thursday 23 November. The series producer is Tim Kirby

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments