The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Bernardine Evaristo: ‘I’m grateful I was the first – but a Black woman hasn’t won the Booker prize since me’

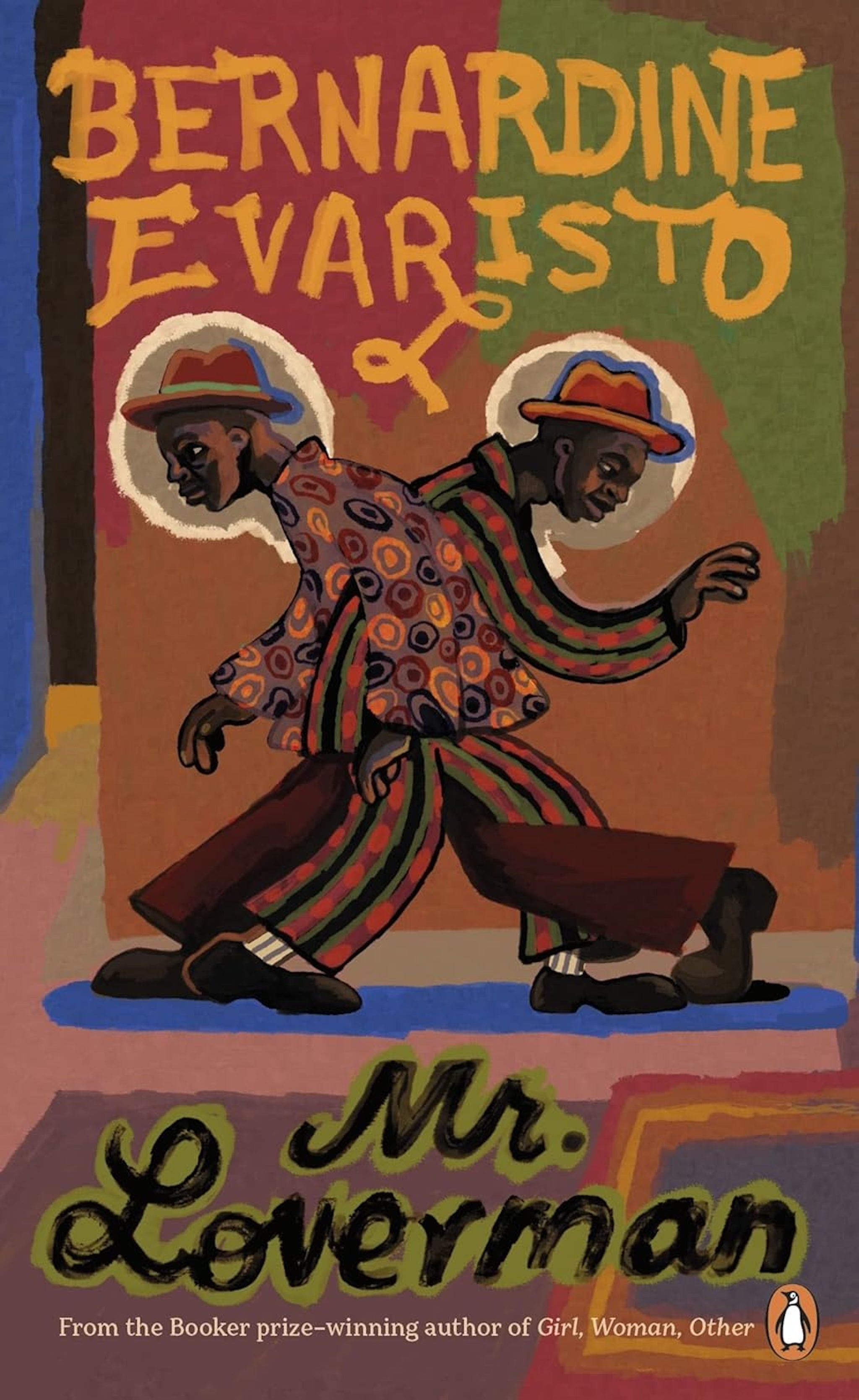

The author of ‘Girl, Woman, Other’, who won the top literary prize in 2019, talks to Annabel Nugent about the moment in her career that made the world take notice, why she is channelling rage into energy, and her novel ‘Mr Loverman’ being adapted for the BBC

When she was 20, the British author Bernardine Evaristo did not own a television. She made the decision to forgo it, she once said, so as not to become a “passive spectator of other people’s success”. From next week, however, telly becomes an integral part of her success as Evaristo’s novel Mr Loverman gets its very own adaptation, courtesy of the BBC.

Evaristo, now 65, isn’t the type of writer to turn up her nose at such opportunities. “Some would say they don’t want their creativity sullied by another medium, but I don’t think I’ve ever felt that,” she says. “No, I’ve always thought it’d be wonderful.” It was a matter of time, really. Evaristo is that rare author whose books have had such a profound impact that she has made the crossing from writer to cultural figure.

She published her first novel, Lara, in 1997 – but it wasn’t until 2019, 22 years and six books later, that the world really took notice. Telling the story of a dozen women, most of whom are Black British, Girl, Woman, Other spanned 100 years and pulled the veil back on subjects such as prejudice, motherhood, sex, race, politics, and art – by then, all familiar themes for Evaristo. What had changed was her audience, newly alert to such issues thanks to the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements. The world, it seems, had finally caught up to her and in 2019, Evaristo made history as the first Black woman to win the Booker Prize. A year later, she was awarded an OBE.

It’s not only Evaristo’s commercial cachet that makes her work suited for a TV adaptation. Her writing, a loose-limbed meeting of prose and poetry, brims with the sort of vigour arguably always destined for the screen.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Mr Loverman, her 2013 novel being brought to life next week. The adaptation stars Lennie James as Barrington, a rambunctious, trilby-hat-wearing, 74-year-old West Indian transplant living in Hackney with his wife Carmel. His true love, however, is not Carmel but his best friend Morris, with whom he has had an affair stretching far back into their youth as boys growing up under the parched sun in Antigua.

Barrington is one of those characters that jumps off the page – a bon vivant who materialises, clear as day, out of dialogue like: “I ain’t no homosexual, I am a… Barrysexual!” (Several snatches of the script are lifted from the book, too good to leave behind in pulp.) Barrington appeared to Evaristo in a similar fashion – such an irrepressible force in her mind that she scrapped a book that was three years in the making to write Mr Loverman instead.

She had, though, anticipated receiving “challenging” feedback on the novel when it was published more than 10 years ago – given that she herself isn’t a seventysomething closeted Caribbean man. “I wondered if I would get it, but it’s not come my way,” Evaristo says happily.

This brings us neatly to the debate du jour: how closely must one’s identity reflect who they portray? James, for example, is also not Antiguan – nor is he gay. Was that something Evaristo was aware of when she learnt he had been cast? She starts to answer, then changes her mind. “I don’t know if I can say this… No, I probably can’t,” she says, switching tack to speak on the subject more generally.

“As creatives, the joy of being a writer or a performer is that you should be able to step inside the shoes of a variety of characters,” she says. “If I were to limit the kinds of fiction that I write to people who come from my demographic, I’d be writing things people wouldn’t want to read.”

Novelists, she adds, are held to a different standard than other writers. “Think of a multidemographic series like Eastenders,” she says. “The logical conclusion to those people who think you should only write from your own community is that you must have 50 writers, each writing exactly who they represent. It’s just ridiculous. It doesn’t make sense.” Certainly, Evaristo could not have embodied all 12 of the women in Girl, Woman, Other.

When Evaristo won the Booker Prize for that novel, her triumph was the result of a five-hour deliberation after which the judges chose to anoint not one winner but two, with Margaret Atwood sharing in the prestigious prize. Together, they took the stage hand in hand to accept the award.

In the weeks afterwards, a BBC presenter discussing the event failed to recall Evaristo by name, referring to her only as “another author”. The irony was not lost on people – and nor was it lost on Evaristo. “I actually found it quite entertaining that he should illustrate part of the problem of the erasure and invisibility of people like myself in this society [so perfectly], that he couldn’t even retain my name in his head,” she says now. You have to laugh, is her point.

For her part, she has never seen her co-victory with an asterisk. “I have nothing negative to say about it at all,” she says. “It changed so much in terms of my career. Put it this way, I don’t think it could have gone any better had I won the prize on my own.”

Girl, Woman, Other launched a second act for Evaristo, one that she admits she had been seeking for years. “I’d been ambitious all my life and I wanted my career to move to another level. At a certain point after I had published several books, I used to say to people, ‘I think I’m going to have to win a big award in order for me to get the kind of attention that I feel I want for my work,’” she says.

I didn’t really care any more about what people knew about me

What is important, and what remains remarkable to Evaristo, is how she won it – on her terms, zero concessions. “It’s a very satisfying experience, actually, because I felt I won it as a Black woman who had written what I think is a radical, experimental, queer, inclusive text,” she says. “And that wasn’t supposed to happen, and it didn’t happen until it happened with me.” The jury is partly to blame; the prize waited nearly 20 years for its first Black or Asian judge. “I am grateful that it happened for me, and that it signalled a breakthrough for Black women,” she says. “Although a Black woman hasn’t won it since…”

While most people new to the spotlight (and scrutiny) of public attention might retreat to the shadows in a spin of existential vertigo, Evaristo doubled down on the exposure. Her next book, Manifesto, was an exuberant memoir that laid bare snippets of her history that interviewers like myself might try for years to elicit: the crushing disappointment of a stalled career; the vicious racism her family faced in 1970s Woolwich; her abusive relationship with an older woman she called “The Mental Dominatrix”.

She had always given interviews about her work, but they “intensified and accelerated” in the wake of her win. “I didn’t really care any more about what people knew about me,” she says. Writing Manifesto felt like the logical next step. “It would be a way for me to put in my own words something of my life and my creativity and how I’d reached this point in my career.” She is pleased to have written it – “because if anybody wants to know about me, they can just go to that book and find out!”

Born to a schoolteacher and a welder, Evaristo and her seven siblings shared one room, until they moved to a bigger house where Evaristo claimed the attic with one of her sisters. Growing up in the Sixties and Seventies in southeast London, Evaristo faced the sort of racism you’d expect a mixed-race girl growing up in the Sixties and Seventies to face. Name-calling. Bricks through the window.

Those experiences and feelings of injustice hardened into political action when she enrolled at college, where Evaristo was one of five Black women on her theatre course. “We began to develop an intellectual understanding of how racism operated, as opposed to just the experience of having gone through it as young people,” she says.

Her first play, The N-Word, was brief and featured only a few words –she jumped onto the stage and shouted the slur at the audience, said something to the effect of “Too Black, not Black enough; too white, not white enough” and then leapt off stage. “An explosion of rage” is how she described it. Certainly, there was plenty to be angry about. “It was definitely useful,” she says of the emotion now. “For myself coming of age, you’re suddenly alert to the injustices in society.”

That coming of age dovetailed with the heyday of her “lesbian era”. Alongside the joyful, sexy portrayal of Barrington and Morris’s relationship in Mr Loverman is a darker homophobia that exists in the city. Happily, this was not her own experience of London. “That definitely did happen in the Eighties, but it didn’t happen to me,” she says.

Still, she and her girlfriends would always be careful about showing affection in public. “I’d say that probably a lot of gay people are still careful about that today. I do not see a lot of gay couples walking hand in hand, maybe in Soho or parts of Hackney, but generally speaking, no.” (Today, she lives with her husband, the writer David Shannon, on the outskirts of west London. They met in 2006 on a dating app.)

When I cut off the dreadlocks and looked a little less androgynous, there was less hostility in the air around me

While she thankfully wasn’t subject to the same violent homophobia as her protagonist in Mr Loverman, Evaristo says she did notice one thing in how people perceived her in those years. “I had dreadlocks for a while. My look was very androgynous, and people used to seem scared of me,” she says. “When I cut off the dreadlocks and looked a little less androgynous, there was less hostility in the air around me.”

There was none from her family, at least. “My family were fine. My siblings were all fine. We’re a very, very liberal family,” she says. “I would say that my father was probably homophobic, but it didn’t affect how he related to me.” Regardless, their opinions would not have changed anything. “I was always going to do my own thing,” she beams. “I was leading my own life, and I was definitely the kind of person who was going to do what she wanted to do. Nobody could tell me otherwise.” She laughs.

Is that still true? “Definitely!” she says. “Although I’m wiser… wiser and much more careful about what I say – in case you hadn’t noticed! And much more strategic. You have to learn how to negotiate this world; when you’re young, you’re putting your foot in it, right, left and centre.”

These days, she has mostly let go of anger – or more accurately, she has metabolised it into something that is more productive. “Rage into energy,” she explains, narrowing her eyes. “Anger is something that can make you self-immolate, but it’s energy that drives my creativity and my activist projects, and which keeps me feeling mentally healthy, robust, and resilient.”

At this stage in her career, Evaristo finds herself in an interesting position. After a lifetime spent writing on the margins, she is now established – part of the establishment, even. In addition to her OBE, she is also president of the Royal Society of Literature – the second woman and the first Black person to hold the position since it was founded in 1820.

“I hold establishment positions, for sure. I can’t deny that. But at the same time, I am a big proponent of inclusion and I take that with me in everything that I do,” she says, when I ask how she feels about her induction. “If I can make a difference in that sense, then I will. So yes, I may be part of the establishment, but by no means does that suggest I’m buying into the status quo.” She pauses for emphasis. “Because I’m not.”

Episodes one and two of ‘Mr Loverman’ will air from 9pm on BBC One on 14 October, with all episodes added to BBC iPlayer the same day

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments