The 20 most defining moments of the BBC, from Prince Andrew’s Newsnight interview to The Office

The launch of Ricky Gervais’s mockumentary and the car-crash interview are just some of the most iconic moments in the corporation’s history. Nick Hilton looks back on the milestones that have made the BBC what it is today

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The BBC is 100 years old. It was formed back in 1922, the same year that the Soviet Union was founded. And while the USSR perhaps shaped the course of 20th-century history more than any other entity, it also collapsed in 1989 – whereas the BBC is going strong to this day. So who’s to say which has the more profound legacy?

It would’ve been hard to predict in 1922, when Lord Reith was tasked with putting together a consortium of British wireless providers, the way that the corporation would develop. The past century has seen the BBC grow from a small-time radio organisation to a global media superpower. The BBC has become one of the world’s biggest digital news sources, it has broadcast coronations and weddings and funerals, Olympics and Euros and World Cups. All to millions of viewers. It has won Oscars and Emmys, broken stories that have rocked governments, and announced wars. And through all of this, it has remained a national fixation. Love it or hate it, revere it or reform it, the BBC has defined the past century of Britishness.

And at the heart of this national obsession is an organisation that has changed with every passing year. Here is a (non-exhaustive) list of 20 moments that have defined the 100-year life of the BBC.

First charter in 1927

The BBC spent the first few years of its existence in a muddy blur, half government initiative and half private enterprise. It wasn’t until 1927 that the first charter was put in place, and Lord Reith was formalised as its first director-general. But more importantly than any of that guff, the 1927 charter guaranteed the BBC’s editorial independence – a pledge that has shaped not just its output over the past century, but also every argument about its future.

Launch of the Natural History Unit

Part One: The BBC has never suffered for lack of nerds, and in 1957 a young David Attenborough was placed in charge of the Travel and Exploration Unit, an outpost of BBC broadcasting that would ultimately become the famed Natural History Unit. Early features included Zoo Quest, in which Attenborough and the staff of London Zoo travelled around the world capturing animals (a premise that would, thankfully, not be allowed in 2022), and Animal Magic, a children’s show that paved the way for The Really Wild Show.

Part Two: Attenborough spent decades fooling around with chimps in jungles of varying states of deforestation, but it wasn’t until Life on Earth in 1979 that he secured his signature essay style. That trademark would later be refined with much more ambitious series (shows where Attenborough was relegated to a disembodied voice, and not allowed to canoodle with orangutans) like 2001’s The Blue Planet and 2006’s Planet Earth. Now, the BBC’s Natural History Unit is world-beating. For many global viewers, the BBC doesn’t mean news or sports or public service broadcasting, but 4K HD shots of penguins sliding on the ice or elephants blowing water at one another.

The Office

When, in July 2001, BBC Two aired an unheralded mockumentary about life at a paper company in Slough, few expected it to change the face of comedy. Fast forward two decades and it’s clear how much of an impact The Office, Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant’s toe-curling sitcom, has had. Not only did it change commissioning tactics, paving the way for cringe-inducing shows such as This Country and Fleabag, it made global stars out of cast members like Gervais and Martin Freeman, and opened the floodgates for 20 years of American remakes of British sitcoms. If grief is the price we pay for love, then Derek is the price we pay for The Office.

Launch of BBC Two

Until well after the Second World War, British television was just two channels: BBC and ITV. The BBC was the eat-your-vegetables channel, while ITV was pure soda-and-sweeties. As a result, the civil service sad-acts decided that the BBC would get an extra channel on which to push its normie agenda. Hence the birth, in 1964, of BBC Two. It was the handsome adaptation of John Galsworthy’s The Forsyte Saga, broadcast a few years later in 1967, that cemented the channel’s place in the British public’s hearts.

Move to Salford

It may have taken the best part of a decade to happen – plans were first announced in 2004 – but the migration of the BBC’s production to Manchester, and, particularly, the brand spanking new MediaCityUK in Salford, symbolised a change of agenda for the Beeb. The years of the Islington set were over; the age of the Timperley gang had begun. The diversification of the workforce, from one urban hub to another, came just in time to watch regional news collapse in every corner of the UK.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Desert Island Discs

In 1964, the sound of tropical birds caused outrage on Radio 4. These flashy substitutes had been brought in to replace the iconic herring gulls in the theme music to Desert Island Discs, the long-running Radio 4 interview show. Herring gulls are natives, predominantly, of the Atlantic, and are about as unsexy as birds go – but the commitment of listeners to their squawking speaks volumes for their devotion to the format. Armed with just eight musical tracks, a book and one luxury item, a celebrity becoming a BBC castaway is a prestigious abandonment. As is the job of anchoring the programme: Roy Plomley’s legendary 40-year stint saw him hand over to Michael Parkinson, Sue Lawley, Kirsty Young and now Lauren Laverne. All are BBC icons in their own right.

London Olympics

The opening ceremony of the London Olympics, a patriot fever dream directed by Danny Boyle, may have aged like cheese in a sauna, but the 2012 Games will be an important part of the BBC’s legacy. The success of both the athletes and London as a host city owes a debt to the quality of coverage, without which events like Super Saturday at the Olympic Stadium would’ve been about as memorable as, uh, anything that happened last year in Tokyo.

Beeb.com/BBC.com

Part One: For many years, I knew the “Habanera” from Bizet’s Carmen only as the theme tune to Beeb.com. What is Beeb.com, you might ask? Well, in the words of the song: “It’s Beeb.com, it’s plain to see/ It’s internet shopping from the BBC.” The service was part of a turn-of-the-millennium drive to bring the BBC into the digital age, but the shopping service ended in 2002. Now, the idea of the BBC providing a competitor to Amazon seems deliciously antiquated; a sign, perhaps, of how fast things have changed in a decade.

Part Two: According to a Press Gazette study, the BBC’s website (snappily named: BBC.com) is the world’s most visited English-language digital news website. That’s a pretty astonishing turnaround from the early days of the BBC’s online output, where it wasn’t just Beeb.com that was heading for disaster. Few will remember the BBC Networking Club, a £12-a-month social network, or BBCi, an interactive digital “umbrella brand” (whatever that means). After a decade chasing the public sector’s tail, the BBC settled on a digital offering that works: the same trusted news resources it perfected on TV and radio, just on the web.

CBBC

It’s hard to believe that it wasn’t until 2002 that the BBC launched CBBC, a channel dedicated to children’s programming that has been a balm to parents everywhere. Even then, it shared its channel with BBC Three, meaning you had to make sure the kids were tucked up in bed by 7pm or they might end up watching Little Britain. Now it has been joined by a pre-school alternative, CBeebies, ensuring that parents can plonk their sprogs in front of the goggle-box from Day One.

The Golden Ages of EastEnders

Part One: Every great soap opera has its Golden Age, when it goes from waiting-room watching to appointment viewing. But when you’ve been on as long as EastEnders, the BBC’s flagship evening serial, you might end up with more than one. In the mid-Eighties, Britain was gripped by the relationship drama of Dirty Den and Angie Watts, which culminated with the serving of divorce papers in the middle of the 1986 Christmas episode.

Part Two: Another epoch was reached in the new century, as EastEnders’ iconic intro came to include the vast white disc of the millennium done, nestled in a kink in the Thames. The drama over “who shot Phil Mitchell” lasted for more than a month in 2001, transforming the soap opera into a weeks-long whodunit. With a revolving cast of suspects including Lucy Benjamin, Martin Kemp and Tamzin Outhwaite, this was EastEnders in its pomp.

Match of the Day (and return in 2004)

Part One: Younger viewers of Match of the Day have probably been struck by the thought: why is it called “match” of the day when it depicts all the matches of the day? Well, in 1964, when the programme first aired, it picked out a single match (in this case, Liverpool vs Arsenal) to broadcast highlights of. The 1960s – if you are entirely new to the idea of football – was a profitable time for the English game. After Bobby Moore lifted the World Cup at Wembley in 1966, MotD became a BBC One regular until 1988, when the rights went to ITV. But that’s not the end of the story…

Part Two: Dun dun dun duhhh, duh duh duh duh duh (can you tell that’s supposed to be the theme tune?). In 2003, the BBC regained the rights to broadcast Premier League highlights, meaning that since the 2004-05 season, viewers of BBC One have had uninterrupted coverage of the day’s highlights package. At the same time, Match of the Day 2 was launched due to the increasing number of English clubs playing midweek European football, which pushed the weekend schedule ever more onto a Sunday. With Sky, BT, Amazon and others all jostling for the Premier League’s broadcast rights, it’s a small miracle that the BBC continues to show its Saturday (and Sunday) night highlights reel.

Queen’s coronation

Though newborn children may not remember her, until September 2022, Great Britain was ruled by Elizabeth II. But before she was the beloved matriarch of an entire nation, she was a true television star: her coronation in 1953 was one of the single most influential moments in British broadcasting. Fuzzy figures from the event suggest that the coronation had 17 viewers to every TV set in the British Isles. The event is also widely credited (though the data seems a little shaky) with increasing television ownership in the UK, and it certainly normalised the idea of communal watching of this nascent technology. Other major state events like the weddings of Charles to Diana and William to Kate, and the funerals of Princess Di, the Duke of Edinburgh, and, spoiler alert, the Queen, have followed the broadcasting protocol laid down in 1953.

Jimmy Savile

It’s not been all rainbows and butterflies for the BBC. Perhaps no incident demonstrates the tendency towards systemic failings more than the case of Jimmy Savile, for years a venerated DJ, game show host and knight of the realm. After his death, it was revealed that he was a sex offender on an almost unprecedented scale. What’s worse is that organisational cover-ups during his lifetime were followed by posthumous carpet sweeping: a Newsnight investigation was shelved, and ITV ended up publishing the exposé. It was a horrifying and deeply unedifying chapter of the Operation Yewtree investigation into historic sex offences, which saw a number of BBC “legends”, like Rolf Harris, Dave Lee Travis and Chris Denning, arrested. The soul-searching following these revelations in 2012 has determined the modern history of the BBC.

Doctor Who regeneration

It is entirely un-British of me, but I’ve not watched a minute of Doctor Who. I gather it is an alien-based children’s show, but what inspires an almost religious devotion in its watchers is the fact of its 2005 resurrection. Having been off the air for 26 years, since Sylvester McCoy’s Doctor whizzed off in his Tardis, Whovians were afraid the show would never return. Enter Russell T Davies and Christopher Eccleston, and a now decades-long run that has made the sci-fi serial one of the great arrows in the BBC’s quiver.

“Reassurance of the pips”

I asked a friend, who works at the Beeb, what he thought was the defining moment of the BBC’s century-long history. “The reassurance of the pips,” he replied, simply. The pips are the Greenwich Time Signal broadcast as six beeps at a one-second delay to mark the precise start of each hour. It is the sort of quirk beloved by radio nerds and subsumed into the subconscious by the rest of us. But more even than the sound of squawking seagulls or Chopin’s “Minute Waltz”, the pips are the signature sound of BBC radio.

Paxman vs Howard, Newsnight I

“Did you threaten to overrule him?” With one simple question (albeit repeated 12 times in quick succession) Jeremy Paxman skewered the then home secretary Michael Howard for his involvement in the case of a sacked prison governor and set the standard for the BBC’s interrogative current affairs broadcasting. Paxman may have the most iconic moment, but he follows a tradition set by Robin Day, and a baton passed to political bloodhounds like Andrew Neil and David Dimbleby.

Maitlis vs Prince Andrew, Newsnight II

Newsnight, however, is not just there to give politicians a hard time. There is perhaps no better example of the frostiness that can occasionally set in between the BBC and the establishment than Emily Maitlis’s 2019 interview with Prince Andrew. In this, now famous, exchange, the prince claimed not to be able to medically sweat and used the Pizza Express in Woking as a dubious alibi. But more than anything, the interview exposed how hot the crucible of BBC political journalism is – and how someone without media training can get incinerated by the slightest contact.

Martin Bashir, Princess Di on Panorama

Maitlis’s interview with Prince Andrew changed the course of his fortunes (he was subsequently stripped of his titles and stood down from public engagements) but no encounter with a royal has been as consequential, or as controversial, as Martin Bashir’s 1995 interview with Princess Diana. “There were three of us in this marriage,” she told the reporter. “So it was a bit crowded.” With those words, the royal family was plunged into crisis. Bashir was one of the BBC’s most daring stars – his 2003 set of interviews with Michael Jackson could also, plausibly, feature on this list – but also one of its most slippery. In 2020, shortly after joining as director-general, Tim Davie issued an apology for the subterfuge used by Bashir in securing the Diana interview.

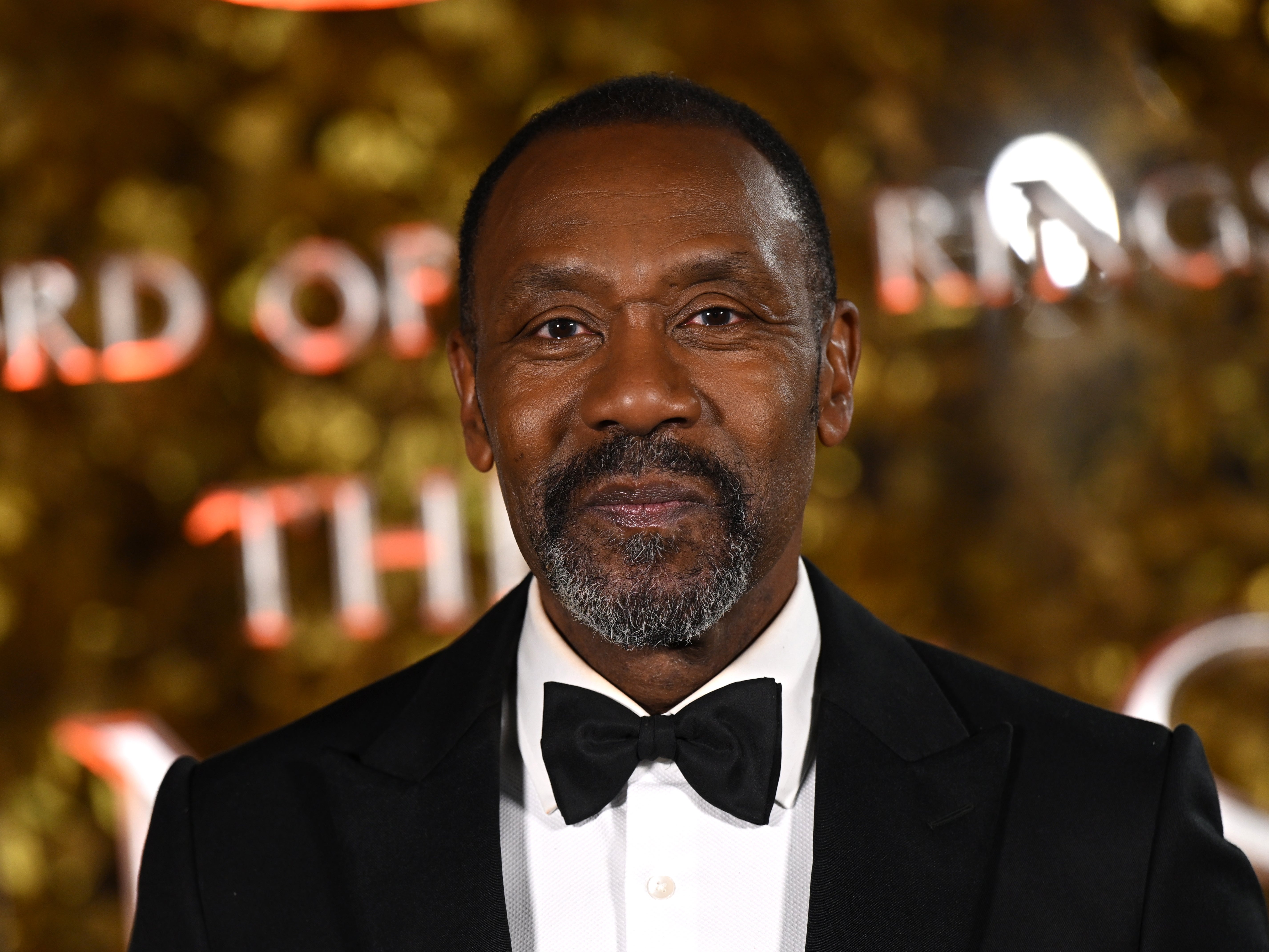

Comic Relief (Ali G, Posh and Becks)

Back in 1985, Richard Curtis, of Notting Hill fame, and Lenny Henry, of being-Lenny-Henry fame, decided to organise a charity fundraiser for famine in Ethiopia. Hence the birth of Comic Relief. In 2015, after 30 years of the event, it was announced that £1.4bn had been raised for charity. Perhaps the standout moment in the event’s history came in 2001 when Ali G (alter ego of comedian Sacha Baron Cohen) sat down with the Beckhams, then the golden couple of British public life. The routine now seems incredibly dated and offensive, but at the time it was a jaw-dropping crossover and a true watercooler moment.

Grace Archer’s death

What happened if you were a voice actress in a hit radio soap petitioning for equal pay in 1955? You got killed off, of course. That’s what happened to Ysanne Churchman, aka Grace Archer, who upset the show’s legendary creator, Godfrey Baseley, with her demands. Grace’s exit has gone down in history as perhaps the essential moment in more than 19,500 episodes of The Archers, a streak that has made it the longest-running serial of any kind in human history. It is a strange, old-fashioned piece of comfort-listening that has endured the tides of fashion since it first aired back in 1950, the year that George Bernard Shaw died, and fuel rationing came to an end. Nothing represents the longevity of the BBC, or its quality of timelessness, better than the residents of Ambridge.

The end of the licence fee?

The extant Royal Charter for the BBC expires in 2027, and the current government has pledged that that moment will also spell the end for the licence fee, the method of funding the corporation. The licence fee, which is presently fixed at £147 per year, has been attacked by Conservatives for a number of years – but even the opposition parties recognise that, in the age of on-demand streaming, there is a need for reform. In January 2022, Nadine Dorries, then the culture secretary, announced the licence fee would end in 2027, and even though she’s subsequently been given her ministerial P45 (and a possible seat in the Lords) it seems likely that 2027 will indeed mark the end of an era for the BBC.

The defining moment of the next 100 years of the BBC’s existence, therefore, might be coming sooner than expected. What would a BBC without the licence fee look like? Scaled-down? Riddled with advertisements? Solely available to deep-pocketed subscribers? What we can be sure of is that public service broadcasting of the next century will look very different to the one that’s come and gone.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments