Life as a Bradford sex worker: has anything changed for prostitutes twenty years on from Band of Gold?

The gritty ITV drama gave a human face to prostitution, but in a city still scarred by memories of the Yorkshire Ripper and Crossbow Cannibal, what is the reality for those in the oldest profession?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It might be difficult to comprehend, in these days of Broadchurch and True Detective, Nordic and Nordic-inspired dramas starkly titled with uncompromising words such as killing, and unforgotten, and missing, but TV drama wasn’t always so gritty.

Indeed, it’s just 20 years since the final run of the ITV series about prostitution in Bradford, Band of Gold… which pretty much set the template for the bleak and grim flavour of crime dramas we can’t get enough of today.

Band of Gold was shocking in the extreme for TV viewers, and came from the pen of Kay Mellor, a Leeds-based writer who then was beginning to make her name inside TV circles by writing for Coronation Street and Brookside.

It’s an oft-told tale how Band of Gold came about. Mellor and her husband were on their way to a party and drove up Lumb Lane, in the Manningham area just outside Bradford city centre. It was November and Mellor saw a young woman, dressed in a tiny miniskirt, freezing in the winter night, standing on the street. The woman looked straight into the car as they drove past; Mellor was shocked by how young she was.

The image refused to leave Mellor, and a few days later she went back to speak to the women, though she never found the girl whose eyes she had met. But their stories fascinated her, and she resolved to write a drama about their lives.

Which was, relatively, the easy part. The tough bit was actually getting someone to make it. She got the BBC interested, but the male executives got cold feet. Mellor told this newspaper in 1996: “It took a woman, Sally Head at Granada, to say that it would be a winner. ITV still hovered for a while. It was probably Band Of Gold’s vocational framework that finally won the day: if you can have firemen, soldiers, doctors and policemen, why not prostitutes?”

Even when it was made, with a stellar cast including Cathy Tyson – who had made her big-screen debut playing a more upmarket sex worker in the film Mona Lisa – singer Barbara Dickson, Geraldine James, and a young Samantha Morton, Mellor still thought “about six people would watch it”. The first episode, broadcast in the now traditional gritty drama slot of 9pm on a Sunday, drew 15 million viewers.

“When I watched Band of Gold, I thought, at last, a drama that puts the women front and centre, rather than them being just a blurred-out image of a woman leaning into a car,” says Cat Stephens, referencing the time-honoured newspaper photograph style used to illustrate any story about prostitution for decades. “The series focused on the women’s lives rather than them being just stereotypes. We’re the sort of people who usually are just plot devices, the people who are murdered in the first scene of a movie.”

When Cat Stephens says “we”, she is talking about sex workers, a job she’s done for the past 15 years. She’s also a volunteer with the International Union of Sex Workers, which campaigns for the human, civil and, yes, labour rights of those who work in the sex industry. Unlike the women portrayed in Band of Gold, Stephens doesn’t work the streets, and says that those who do account for a minority of UK sex workers.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

“We think there are around 80,000 sex workers in the country,” she says. “But for obvious reasons that’s pretty wobbly data, and probably a bit out of date, but that’s the sort of figure we have. And estimates for the numbers of women who work on the street range from as low as 3,000 up to 22,000… even at the top end that’s just a little more than a quarter.”

But they are there, of course. And over the past two decades, has anything changed from the gritty days of Band of Gold, which though drama was based on fact? For those involved in managing the impact sex work has on the local community, things have changed… but not necessarily for the better.

Cllr Andrew Mallinson is a representative of Bradford Council on the West Yorkshire Police Crime Commissioner’s Panel, scrutinising the work of the police force including its policing of sex work and prostitution. Around 18 months ago, Cllr Mallinson suggested that Bradford should follow the example of Liverpool and neighbouring Leeds, and make designated zones for prostitution in the city.

“I wasn’t suggesting we legalise it, but having prostitution in a known area would be beneficial, I thought,” he says. “People would be aware of these zones, could avoid them if they wanted to, and they would be easier to contain. I tried to talk to the police and they absolutely refused to hear me out. I asked senior officers to accompany me to Leeds to look at how it was working there – but nothing.”

It’s possible that some circumstances are more severe than they were back when ‘Band of Gold’ was shown. There is severe deprivation, particularly in housing conditions, which might serve to push more people into sex work

As a councillor, Mallinson is aware of the impact of prostitution on local communities. “It can be intimidating for people who live in areas where it’s going on, and once an area gets a reputation that can stick a bit… even 20 years on from Band of Gold, if you go for a job and say you live on Lumb Lane, that might cause eyebrows to be raised.

“There are periodic zero tolerance policing initiatives but all that does is move it on to another street a mile, two miles away, and then when things have quietened down they come back.”

But the Conservative councillor isn’t just concerned about residents. He says, “I think over the past 20 years attitudes have changed, and hopefully the police and local authorities are a lot more concerned about the welfare of the women who are working in the sex industry. There is a lot more consideration of the problems that can drive women into this sort of work, be it drugs, or alcohol or debt. There’s more thought about the human element of it rather than just as criminal behaviour.

“That said, I think there are issues that are facing women working in the sex industry that might be worse than they were 20 years ago. There seems to be more of an influence from Eastern Europe these days, and that seems to change the complexion in that there is possibly a more aggressive manner in which the trade is plied. And there is a lot of sexual abuse and exploitation of women still.

“It’s possible that some circumstances are more severe than they were back when Band of Gold was shown. There is severe deprivation, particularly in housing conditions, which might serve to push more people into sex work.”

Cllr Mallinson remembers Band of Gold well, particularly some of the responses within Bradford that were unhappy about a perceived negative portrayal of the city on national TV. He says, “But I think it portrayed the issue very well.”

Band of Gold’s broadcast was flanked by two international news stories that also showed Bradford and its sex industry in a less than positive sheen, but which had a far, far more horrific impact for the women involved.

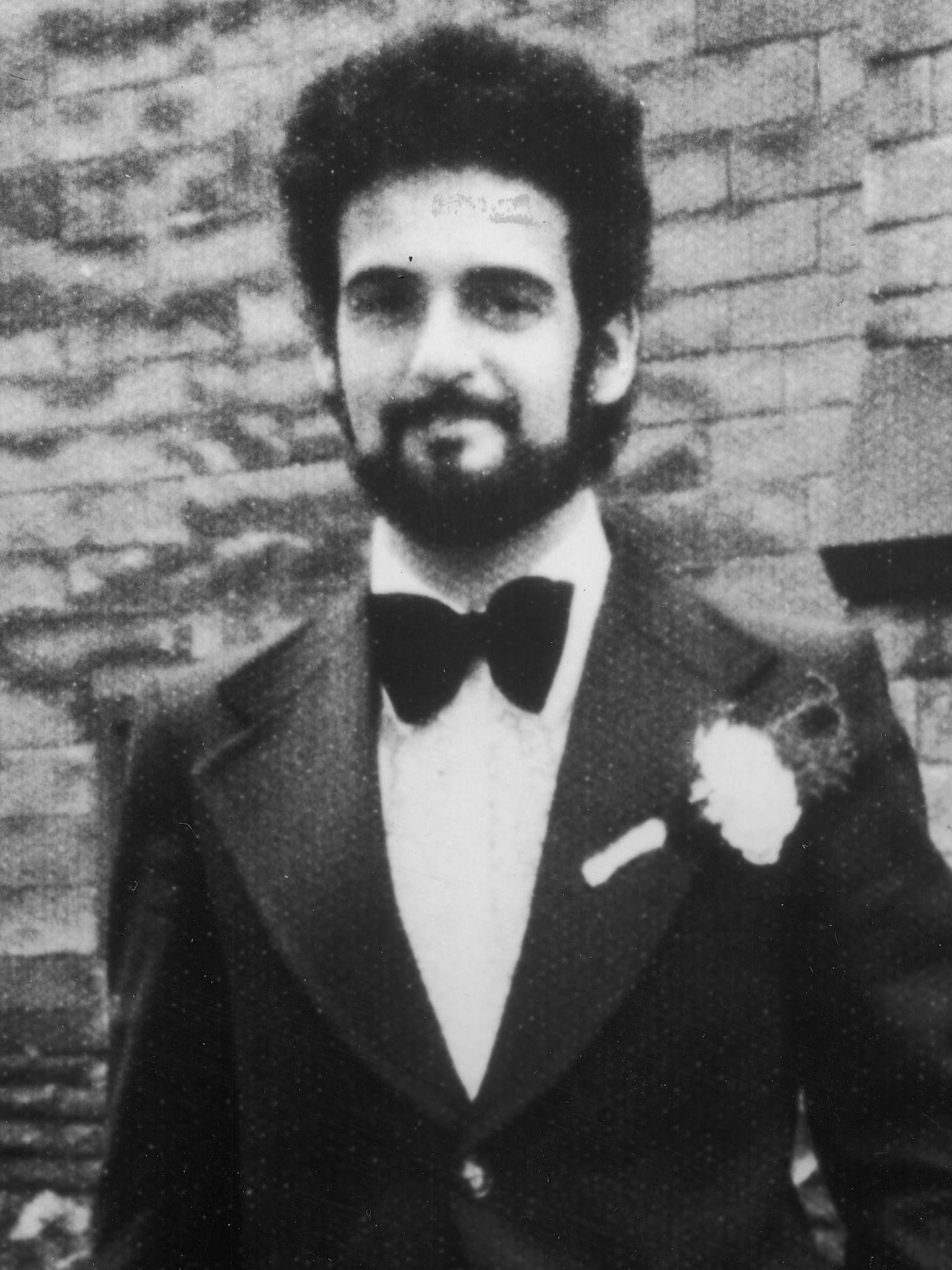

In 1981, Bradford lorry driver Peter Sutcliffe was convicted of murdering 13 women and attempting to murder seven others. The so-called Yorkshire Ripper claimed he was on a mission from God to kill prostitutes. And in 2010 Stephen Griffiths – revelling in court in his tabloid appellation of the Crossbow Cannibal – was jailed for life for the killing of three sex workers in Bradford.

Perhaps they could have happened anywhere. But they happened in Bradford. Still, both sets of killings were the work of disturbed individuals. Surely rare dangers for women working the streets. Not necessarily, says Cat Stephens, who points to the Policing and Crime Act 2009 as actually making things worse for the women on the streets.

“The Act created a definition of ‘persistent’ offending and said this meant four lots of contact with the police over a year without being prosecuted,” she says. “But effectively this meant that if a street sex worker had been spoken to by the police a month ago, she would go out of her way to avoid them, meaning she might go to less well-lit areas, wouldn’t want to be seen talking too long to men so might jump in a car before checking them out properly, and would be more easily persuaded to go to unfamiliar areas to have sex.”

Equally, tougher enforcement on customers ultimately leads to an increased likelihood of violence and contact with more undesirable and unpredictable customers. With greater fear of prosecution, those with most to lose – married men with families, men with “respectable” lives or jobs – are less likely to take the risk. Those with less – or nothing – to lose will not be put off visiting the red light districts. Perhaps the Peter Sutcliffes and Stephen Griffiths of this world.

That said, says Stephens, the biggest threats of violence for sex workers do not come from punters but from the general public. When the Lumb Lane area featured in Band of Gold was the haunt of sex workers in real life, there were stories of residents getting up vigilante patrols to move the problem on themselves.

“What this means is shouts of abuse, cups of urine thrown from car windows, and actual assaults that lead to hospitalisation,” she says. “And often this never leads to any prosecution. It’s almost as though the police turn a blind eye.”

Although the sex worker-turned-union-volunteer and the Conservative councillor might seem, on the surface, poles apart in terms of ideology, they both tend to think the answer to the ongoing issue of prostitution is essentially the same: decriminalisation.

Band of Gold might have been a TV drama that ushered in a new era of “gritty” television, but for the women who still work the streets in Bradford and beyond two decades on, fiction has nothing on real life.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments