Thomas and Mary: A Love Story, by Tim Parks; book review

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

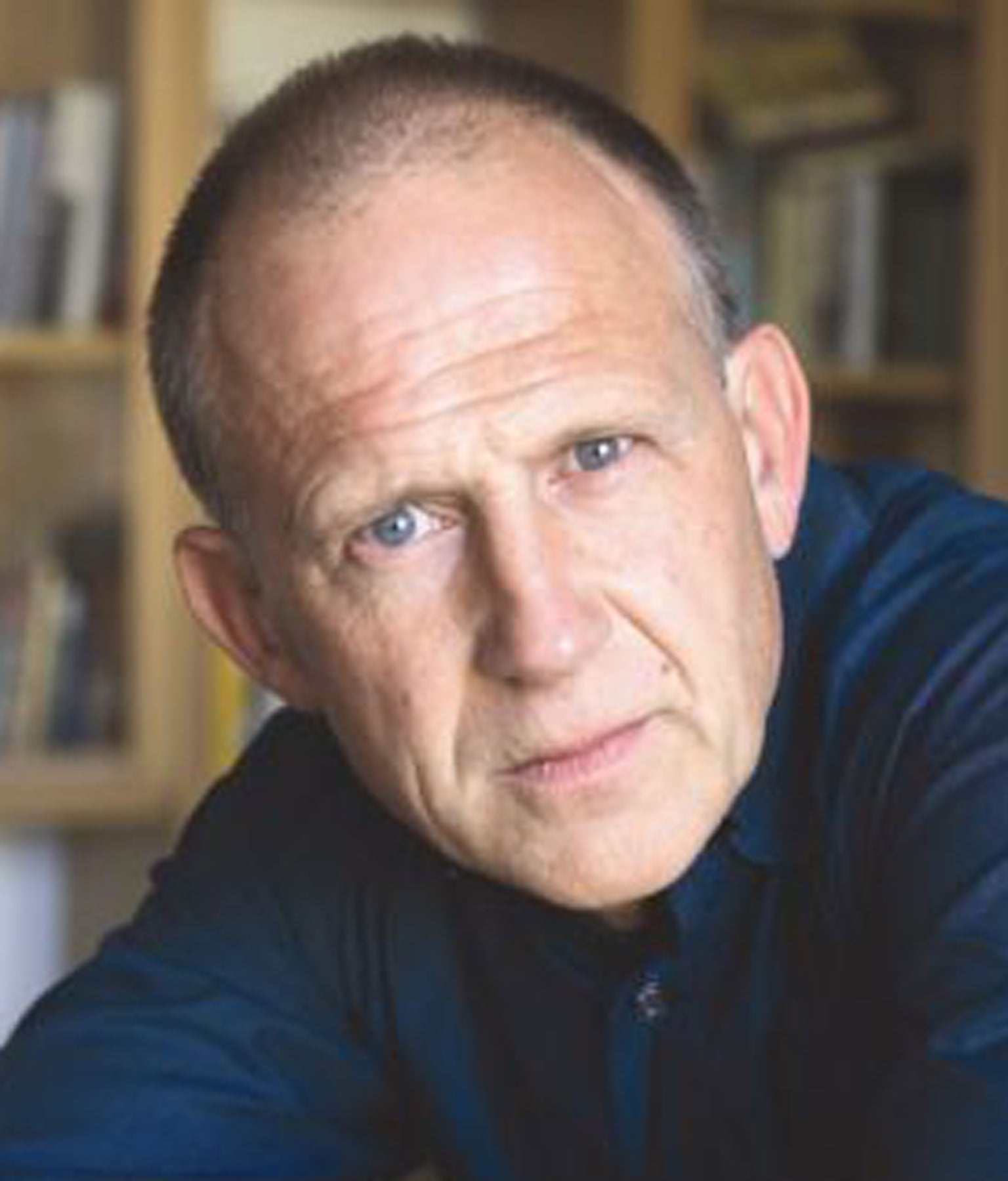

Your support makes all the difference.At first glance, Thomas and Mary: A Love Story doesn’t seem like a love story at all. There is no grand romance, no heartbreak, no passionate longings nor evil deceptions. Just a slightly disgruntled married couple, Thomas and Mary, who have been together thirty years and are not sure where to go next. But an exploration of this deadlock is precisely where the magic of Tim Parks’ new novel lies. Thomas and Mary are in that sticky place, where things are neither clearly good nor bad, but there is a vague sensation that things could, perhaps should, change. In this darkly funny work, Parks offers a story that doesn’t shy away from the complexity of relationships, and from the ineffability, indeed, impossibility, of the unmade decision.

The novel begins with short, simple sentences that reflect the banal, mechanical nature of the couple’s relationship: "Monday evening, 10.30. Thomas is sitting of the sofa with his laptop reading for work. Mary has been talking to a friend". The reverberations of their muted conflict travel onwards, affecting their parents, their friends, and in a particularly engaging section, their teenage son, who stews in self-loathing and seeks escape in the arms of an alluring, dope-smoking girlfriend. The danger of remaining in a state of limbo is highlighted through the threat of mortality, reflected in the deterioration of an ailing parent. And as the novel proceeds, the reader cannot help but will for something to give way.

Parks resists the novelist’s temptation to provide a clean narrative arc. Real life is more complicated than that. Every truth has multiple perspectives; you pull at one end, and the other changes. "How to tell a story that is quicksand?" Thomas wonders while trying to unpack his relationship. The answer, Parks seems to offer, is to talk around the inexplicable. What it is that needs to shift in the relationship perplexes reader and protagonists alike, but instead of easy answers, we are offered only the facts. Thomas dreams of earthquakes and storms; Mary buys a dog on which to lavish her love. There are small infidelities and rebellions, masking deeper discontent. And as the situation develops, there is a growing sense that we have less agency in our lives than we imagine, that perhaps all we can really do is observe life unfold. In this, Parks once again defies novelistic convention, allowing his characters to experience rather than to act. Thus, as movement begins to manifest, Thomas is described as "imagining he hadn’t yet quite taken a decision that life had taken for him more than a decade ago". And when some semblance of resolution does arrive, as in life, the results appear both unexpected and inevitable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments