Theatre review: Much Ado About Nothing

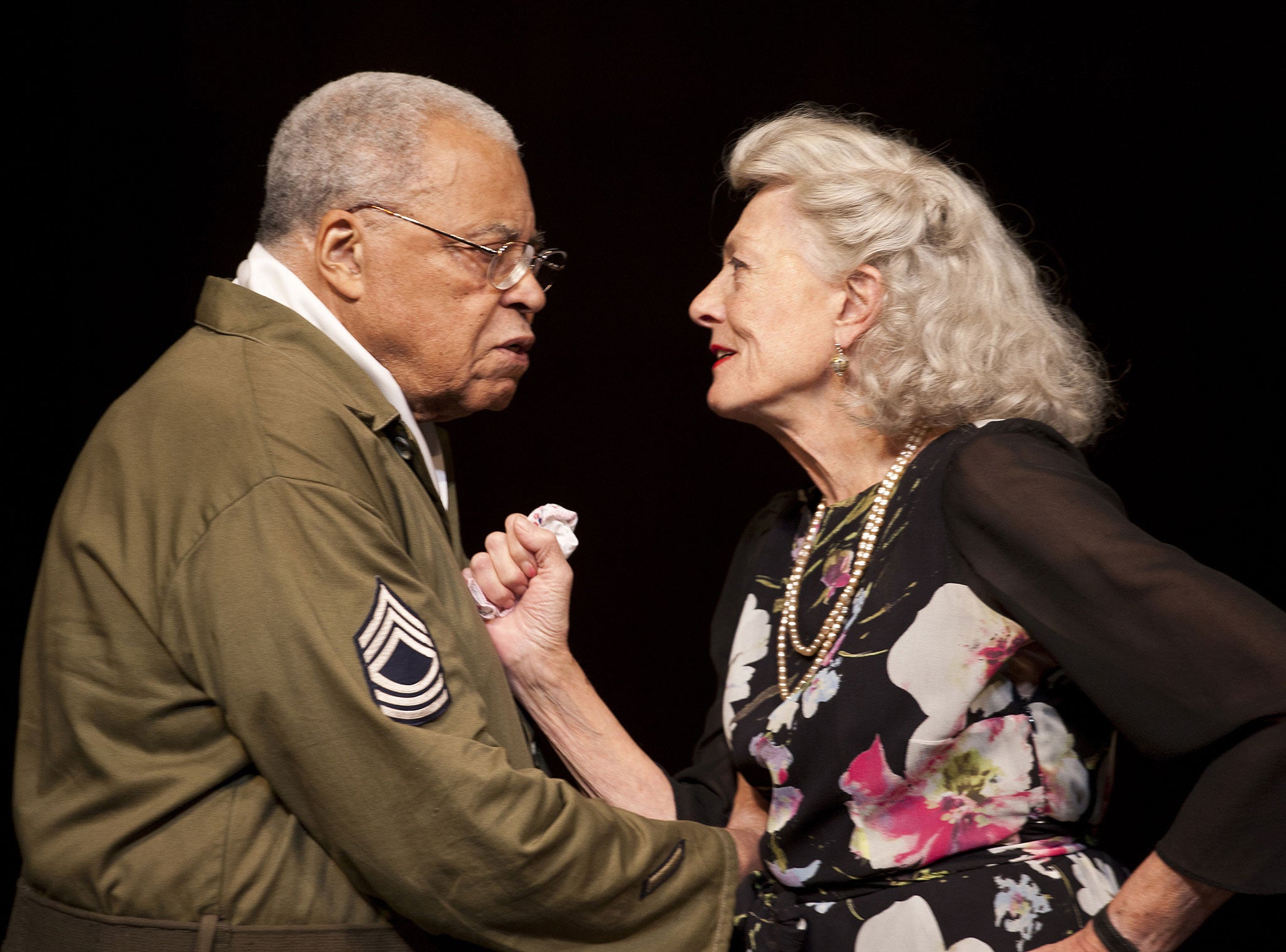

James Earl Jones and Vanessa Redgrave fail to sparkle

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Admirers of the chemistry between Vanessa Redgrave and James Earl Jones in Driving Miss Daisy can scarcely have dreamt that the next time they saw this pair on stage it would be as Beatrice and Benedick, the sparring, reluctant lovers in Much Ado About Nothing. But Mark Rylance was so impressed by their affinity that he has built this production around them. It's a bold experiment that was always destined, one felt, to be either a transcendent exercise in age-blind casting (these great veterans have a combined age of 158) or a misconceived mess. I regret to say that it is very much the latter.

What one had not anticipated was that it would be dreary as well as incoherent. Since Jones is American, Rylance has had the idea of presenting the troops as a company of black GIs billeted in rural England in 1944. The literal-minded objections to a world in which nieces look longer in the tooth than their uncles and in which the army evidently has no retirement age would matter less, if Redgrave and Jones were able to produce verbal fireworks. Beatrice and Benedick are often portrayed as on the verge of middle age, their witty skirmishes springing from a defensiveness about their feelings, but here there's no spikiness or sparkle to the rallies.

Fumbling and slow, Jones is, to put it mildly, not in command of the witty rhetorical patterning of the speeches. He's an engaging presence, but the un-funniness of the performance is exacerbated by the ineptitude of the staging. In the great gulling scene, he winds up completely concealed in a wooden cart which is bizarrely self-defeating when the comedy of the episode depends upon our being able to see his shocked reaction to the deception. Carrying a brace of dead rabbits and a shot-gun on her first appearance, Redgrave is not much better. She has a certain creaky swagger, but her delivery feels vague, woolly and under-powered and quite at variance with Benedick's view that "she speaks poniards, and every word stabs".

The spirits aren't exactly lifted by Ultz's drab brown design which divides the acting area awkwardly with a rectangular arch. The 1940s setting allows for a couple of welcome musical respites – a lovely bluesy harmonica-led rendition of "Sigh No More" and a "GI Jive" dance finale which the leading couple sit out, hidden by the copy of The Times that they are reading. It's painful to see two such great actors in a context that does them no favours. They generate good will because of who they are, but the production which has been tailored as a vehicle for them can't, alas, be pronounced road-worthy.

To 30 November; 0844 8717628

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments