The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus, Finborough Theatre, London, review: an intellectual pantomime

Poet Tony Harrison’s play ‘The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus’ gets its first London production since 1990

Tony Harrison's play is an altogether extraordinary work: an intricate palimpsest, an intellectual pantomime and an impassioned critique of cultural elitisim that features clog-dancing, phallus-waving gods; rumbustious rhyming couplets, and a pair of highly strung archaeologists who become weirdly incorporated into the fragmentary Satyr play by Sophocles (the Ichneutae) that that they have discovered.

Trackers was premiered in the ancient stadium of Delphi in 1988 and two years later appeared in the Olivier. It has not had a major London revival since then. So the theatrical year gets off to a bracingly counter-intuitive start now with this punchily persuasive production by Jimmy Walters that manages to convert a piece associated with big public arenas into a powerful close-up assault. How the various strands hang together tonally could, at times, be clearer, and the fine company could give the audience permission to laugh more often. But I did not find the experience overbearing and the spirit that animates the writing comes over rich and strong.

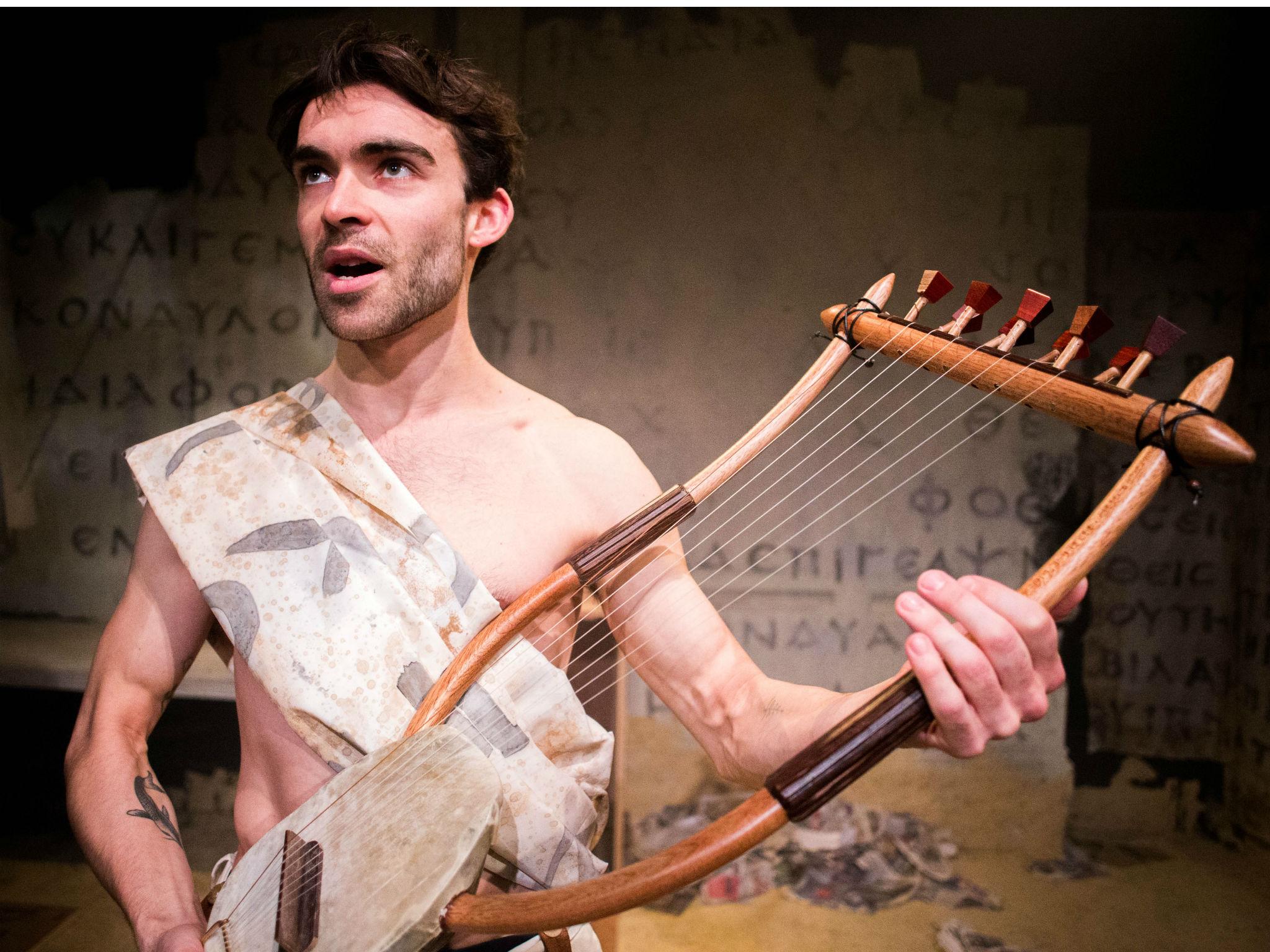

We begin in 1907 in Egypt where the two archaeologists, aided by their felaheen, are sifting through the rubbish tips in search for fragments of papyrus. The relatively equable Hunt (Richard Glaves) is patiently interested in all the bits of mundane petitions from, say, the homeless of the period that they unearth. The manically driven Grenfell (Tom Purbeck) is haunted by the thought of the literary masterpieces that might by mouldering unnoticed: “How can a person sleep/while Sophocles is rotting on an ancient rubbish heap?”. Near to collapse, Grenfell becomes possessed by the spirit of Apollo who threatens to pursue him till he finds the play in which the god has a starring role. In a startling coup de theatre, the bare-chested satyrs burst out of packing crates, with their woolly phalluses and stompy dances, and the piece ingeniously interlaces the scholars’ “tracking” of the lost Sophoclean play with that play's own story of the satyrs' tracking of Apollo's missing cattle.

It's eventually discovered that the precocious infant Hermes (Dylan Mason in a sagging nappy of papyrus fragments) has stolen these creatures and has used their body parts (along with a tortoise shell) to fashion the first lyre. By this stage, Purbeck's Apollo has become the deeply unpleasant god of cultural exclusivity, appropriating the lyre and snobbishly suggesting that the satyrs are too lowly to appreciate any music it might make. As a rebuke to that, in what is perhaps the finest sustained sequence of poetry in the piece, Glaves (who has metamorphosed from Hunt to Silenus) gives a magnificently excoriating account of how Marsyas, brother satyr, was flayed alive for displeasing Athene with his virtuoso prowess on the flute: “It confounded the categories of high and low/when Caliban could outplay Prospero”. Athene did not like the way her cheeks looked while practising

Picking up the references to the homeless in those scraps of petitions in the early scenes, Trackers becomes a troubled meditation on what it is to be exiled from one’s culture. The dispossessed satyrs have their descendants, it’s suggested, in the dossers living rough in cardboard cities in our own times. I’m not sure, however, that it is exclusion from high culture that leads to people becoming literally homeless. A flaunted ignorance of such culture does not, these days, stop anyone from being comfortably domiciled. I found the spectacle of the down-and-outs about to drown under bits of Greek (the excellent, resourceful design is by Phil Lindley) less haunting than the climactic sight of Glaves's beaten-up and derided Silenus deciding to go into territory forbidden to satyrs and mount the tragic stage. For a tragedy is what Trackers becomes. Recommended.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments