The Lady from the Sea, Donmar Warehouse, London, review: Full of finely angled performances

Elinor Cook’s sharp adaptation moves Ibsen’s play from the icy fjords of Norway in the 1880s to the sticky heat of the Caribbean in the 1950s

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

The Lady from the Sea is one of the strangest and most haunting of Ibsen’s works. It’s as though a play of bourgeois realism, such as A Doll’s House, with its concern for finding a true and just basis for marriage has been crossed with a starkly symbolic pre-Freudian folk tale about the sufferings of a stranded mermaid. Seeking security, Ellida Wangel has settled for life as the second wife of a decent but dull provincial doctor and as the stepmother to his two resentful daughters. But she feels stifled and pines for the sea, consumed with dread and longing by the memory of the mysterious sailor whose spell she came under when she was 16. Guilty of murder, he was forced to flee, but the two were betrothed by the ceremony of throwing rings into the waves and now, many years later, this blatant symbol of unbridled desire has returned to claim her. Which life will she choose?

In his first production since he was appointed artistic director-elect of the Young Vic, Kwame Kwei-Armah gives us a strikingly fresh sense of the fascination of the piece and of its forward-looking wisdom about gender relations. Elinor Cook’s sharp adaptation shifts the play from the icy fjords of Norway in the 1880s to the sticky heat of the Caribbean in the 1950s. Race does not become an overt issue, but the relocation to a post-colonial British island manages to update the proceedings, while also emphasising the social expectations that make this less of a paradise than it looks for the female characters in the play. They all feel as trapped and as cut off from the great ocean of life as the carp, imported from Europe, in the ornamental pond. Seawater would kill these fish, but at least they would have tasted freedom for a moment...

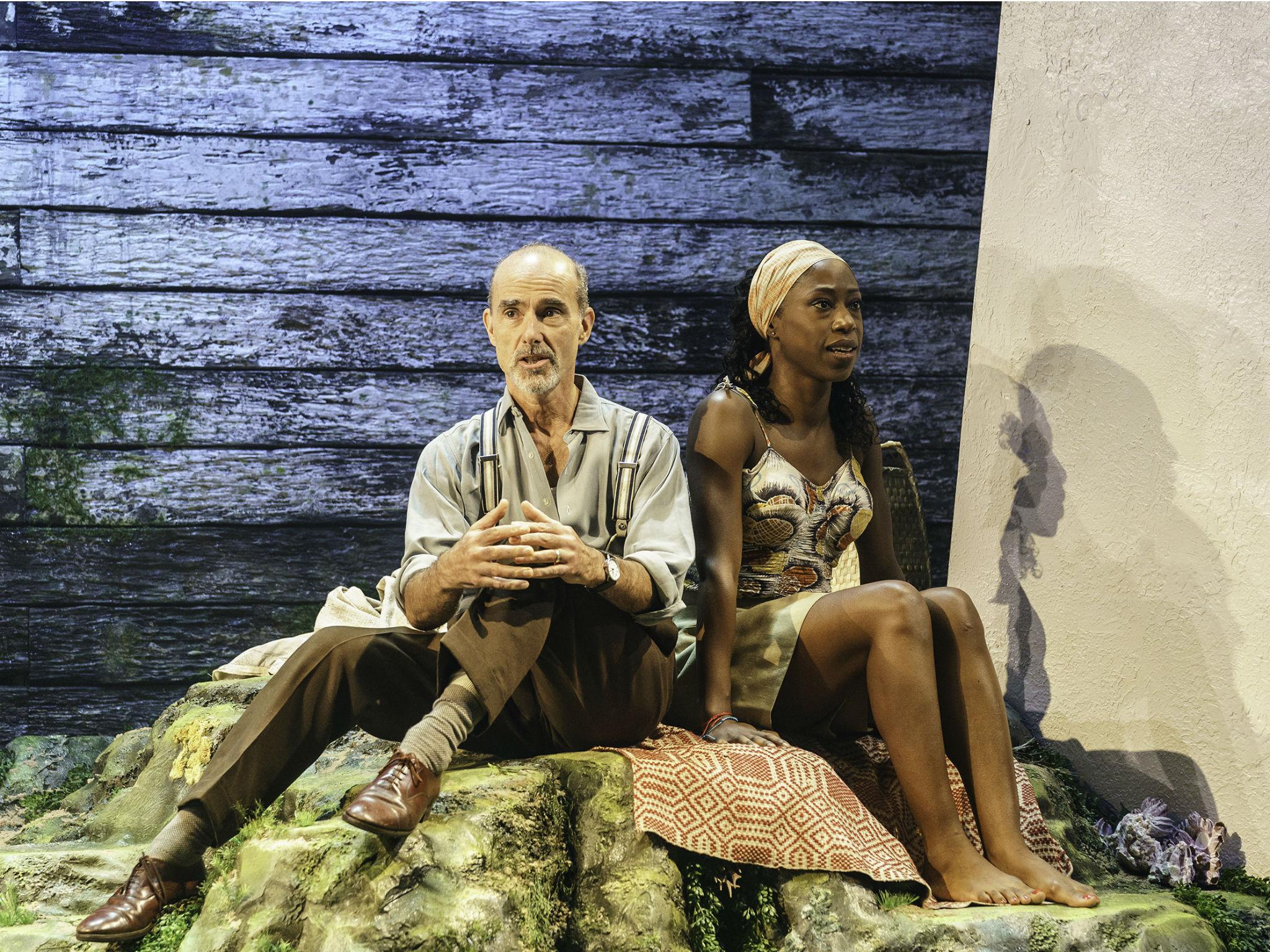

Nikki Amuka-Bird’s impressive Ellida is no otherworldly dreamer but an intelligent modern woman, fished out of her natural element and wrestling with some terrible demons, such as the thought that – impossibly but horribly – her baby son who died had the eyes of the Stranger. Finbar Lynch nails the genuine, professional but unimaginative solicitude of her doctor husband who has infantilised Ellida through his cosseting, leaving her with less responsibility than his daughters for running the household. Crucially, what she craves is that she should now have complete freedom to choose between the two competing forms of existence and in the charged moment when the doctor finally understands what she means and releases her from her vows, the hold of the Stranger (who looks like a ghostly figment of strapping manliness in Jake Fairbrother’s performance) is summarily broken.

The production is full of finely angled performances. Helena Wilson makes a particularly strong impression as the spiky, clever Bolette, who is here achingly torn between the desire for further education in Europe and a sense of duty to stay and look after her father. Usually, you feel that this character might be entering into the sort of bargain that was her stepmother’s big mistake when she accepts the hand of her former tutor, Arnholm. In Cook’s version, though, Bolette is much more astute about men who may think that they want to free women but “just want us to be duller, weaker versions of themselves”, while Tom McKay’s watchful and perceptive Arnholm is able to suppress his ego and have her best interests at heart. This indefinitely postponed marriage bids fair to rest on a secure foundation.

Attractively designed by Tom Scutt and lit with a subtle feel for the play’s eerie tensions by Lee Curran, this version of Lady from the Sea draws on its Caribbean setting for some fine moments of humour. I liked that among the many jobs (decorator, dance teacher, steel band member etc) that Jim Findley’s “Renaissance man” Ballestred, is holding down, there’s attending to the coiffure of women whose hair-dos have drooped because of the humidity. Recommended.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments