Shakespeare: Staging the World, British Museum, London

The Bard's glorious, grisly, world springs to life. Verily, it's a triumph!

The skull of a bear that died in a baiting session – the dog tooth marks still visible centuries later – is just one reminder that in Shakespeare's world the division between civilisation and savagery was far slimmer than today. Now, newspaper headlines fret about gun-toting gang culture, but in the first Elizabethan era few educated gentlemen were to be seen without a rapier and dagger, and – as the exhibition commentary reminds us – they were ready to fight at any provocation.

For the great paradox of Shakespeare's legacy is that while we remember him through his words, it is his ability to convey the visceral as much as the cerebral aspects of life that preserves him in our cultural bloodstream. This beautifully curated exhibition gives us enjoyably idiosyncratic access to the different worlds that informed the vision that he presented at The Globe, but the aggression that shaped them is never far below the surface.

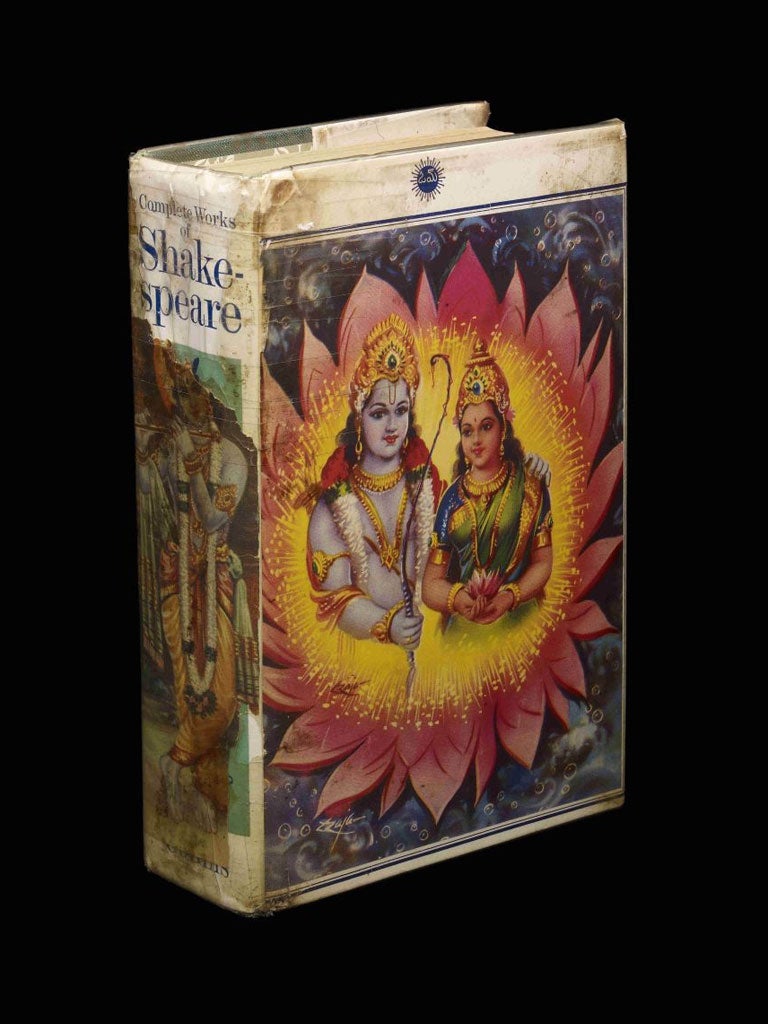

Copies of the Bard's complete works open and conclude the exhibition, and the final one (known as The Robben Island Bible because it was shared between imprisoned ANC activists) is annotated by Nelson Mandela and others. There is also, tantalisingly, the only surviving example of a manuscript in Shakespeare's handwriting, which is the closest the exhibition gets to the scholastic minefield of his identity. This extract from Sir Thomas More, which he co-authored, reveals a neat, looping hand, meat for amateur and expert graphologists alike.

The display encompasses real and imaginary worlds. It starts in London with a 1647 map where the main features are St Paul's Cathedral, London Bridge, the Tower of London, and the Globe, amusingly mislabelled as a bear-baiting house. In many ways this map functions as a metaphor for our relationship with the Bard's world. While the names are similar, they evoke different architecture: St Paul's is in its pre-Wren incarnation and spireless, and London Bridge, groaning under a cluster of buildings, is the only Thames crossing. Shakespeare: Staging the World cleverly shows how a historical understanding of the places and things that Shakespeare knew peel away layers of meaning in his plays.

The most grisly of these objects is a reliquary containing the right eye of Edward Oldcorne, a Jesuit priest who was executed because of his (highly disputed) connection to the Gunpowder Plot. Shakespeare wrote Macbeth one year later, and "the Scottish play" can be read in part as a direct warning of the gruesome end that can come to regicides. Macbeth is also, of course, a demonstration of how the Bard used both historical and mythical worlds to displace political messages that would have been unpalatable in acontemporary theatre. A section on the classical world shows how the affair in Antony and Cleopatra parallels aspects of the romance between Elizabeth I and the Earl of Essex. (As well as burying the allusion in mythologised history, Shakespeare waited till Elizabeth was safely dead to produce it.)

Paintings that form a dialogue with the Bard's world include a gilded medieval portrait of a magisterial Richard II that conflicts starkly with Shakespeare's picture of the flawed monarch. By contrast, the stern gaze of Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud – the Moroccan ambassador to the court of Elizabeth I – suggests a source for the playwright's concept of the noble Moor Othello.

No exhibition could properly evoke Britain's greatest cultural export without reminding us of the rhythm and impact of his language. Luckily, the British Museum's collaboration with the RSC means that filmed monologues from his plays (with actors including Antony Sher, who also narrates the audioguide, and Paterson Joseph) resonate around the displays, while managing to be unobtrusive.

This is a triumph of detail and invention, both impressively scholastic and beguilingly playful. The exhibits may be in glass cases, but they provide a vivid conduit to the Bard's multi-layered universe.

'Shakespeare: Staging the World' (020-7323 8181) to 25 Nov

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments