La Damnation de Faust review, Glyndebourne Festival Opera: An extraordinary work

The warp and weft of the staging is a stunning amalgam of sound and vision

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You couldn’t ask for a better example of creative possession than Berlioz’s musical response to Gerard de Nerval’s poems on Goethe’s Faust. “I wrote it when I could and where I could,” said Berlioz of the emerging score of La Damnation de Faust. He wrote it night and day, everywhere he went, in a frenzy of excitement. It was to be a concert work, not an opera, but it’s as an opera that it’s now increasingly presented, despite the fact that its internal logic, though dramatic, is not at all theatrical. It has the momentum of a dream, and the art-form with which it has most in common is film.

This is why Richard Jones’s new Glyndebourne production works so perfectly, because Jones has seized the chance – or taken the liberty – of imposing his own somnambulistic narrative on Berlioz’s loosely linked succession of scenes. Because Berlioz begins the action, such as it is, with Faust dreaming of the beauty of the plains of Hungary, Jones can open with the framing device of a stagey address to the audience in which Mephistopheles explains why he is going to destroy the “idiotic” Faust.

And here much of the work is set in a Ruritanian school for army cadets, which allows its own brand of comedy. The fact that Jones’s take on the plot is fairly preposterous matters little: what counts is the warp and weft of his staging, which is a stunning amalgam of sound and vision for which his production team – designers Hyemi Shin and Nicky Gillibrand, lighting designer Andreas Fuchs and above all choreographer Sarah Fahie – deserve accolades.

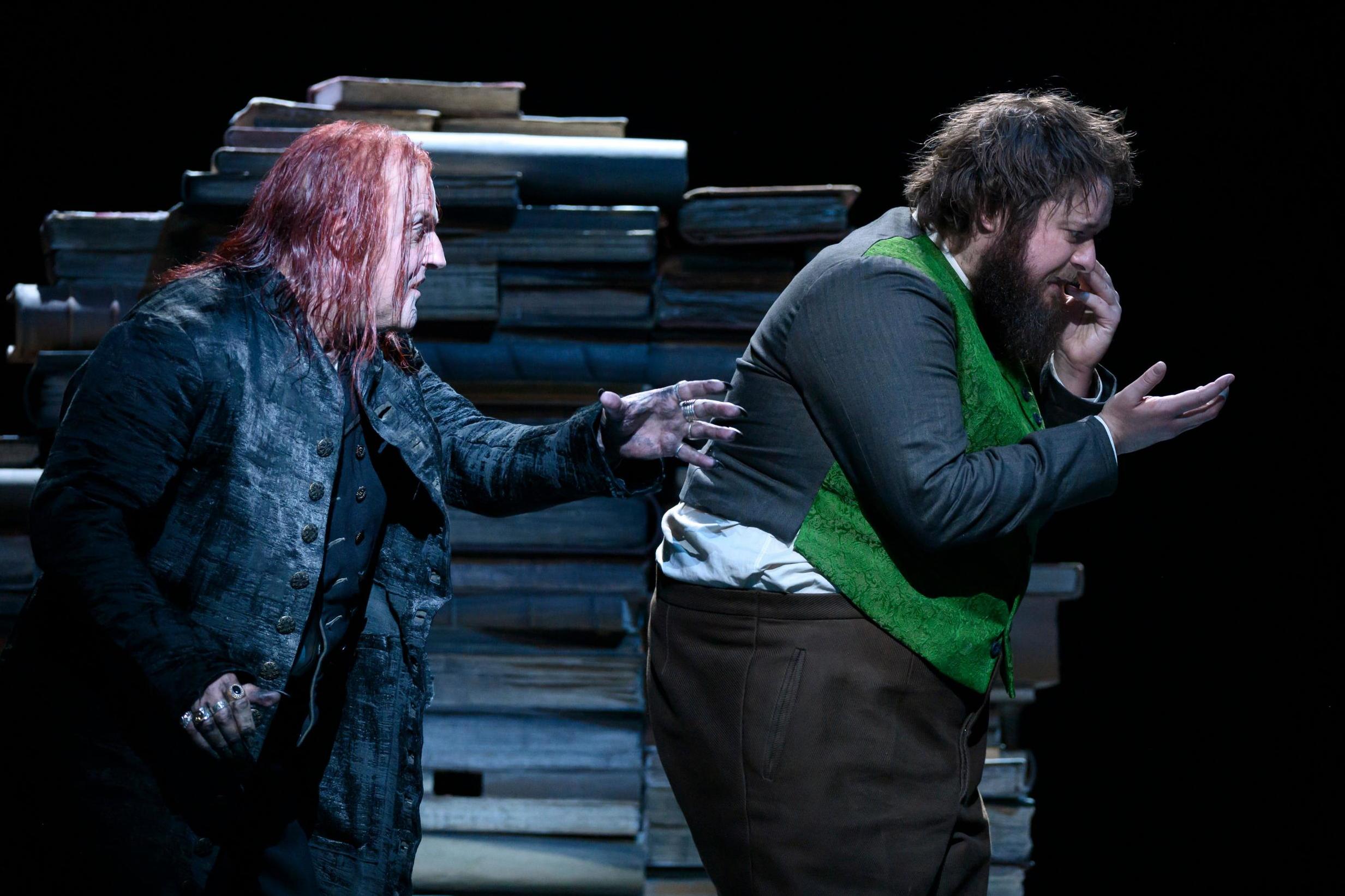

The curtain goes up on a square black box, along the top of which sit rows of horned and brightly painted devil figures, while other devils limber up like athletes below. If it all looks like fun, it remains so as Christopher Purves’ Mephistopheles addresses us in orotund tones redolent of the old Comédie Francaise. While the music maintains a swooning momentum, the physical action is fast, fanciful and often comic, but somehow the two meld powerfully, rather than neutralising each other. At times the air seems thick with tumbling, flying bodies; the chorus and dancers alternate between slow-mo, freeze-frame and frenzied movement as though they constitute one single multi-limbed organism. And the forces Jones deploys are huge: a chorus of 64 singers, a children’s chorus of 35, 14 actors and four principal singers.

But those four are what this extraordinary work is all about. The excellent Ashley Riches dominates the tavern scene imperiously. Christopher Purves makes a convincingly sly Mephistopheles, even if the expected swagger is somewhat muted. But Julie Boulianne’s Marguerite is gloriously sung, her sound replete with grace and power. And Allan Clayton’s Faust is vocally all that could be desired, even in the almost impossibly high notes of his duet with his lover. His lyrical singing has an unforced beauty which never flags, despite the fact that he’s onstage at almost every moment. The mercurially kaleidoscopic score is rendered with fastidious attention to detail by the London Philharmonic under Robin Ticciati’s direction. A lovely evening.

Until 10 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments