IoS dance review: Royal Ballet Triple Bill, Royal Opera House, London The Lock In, The Brook Theatre, Chatham

Three works by Kenneth MacMillan are a welcome reminder of what ballet can do. In another dance universe, folk and hip-hop unite to stunning effect

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Silence doesn't sit easily in a ballet. And it's the absence of music – or any sound at all other than the urgent smack of mouth-on-mouth in an illicit clinch – that galvanises the opening of Las Hermanas (The Sisters). It was made in 1963 and it's still shocking.

At the centre of The Royal Ballet's latest triple bill is Kenneth MacMillan's grim, graphic concentrate of Federico Garcia Lorca's play The House of Bernarda Alba, the story of five sisters house-bound by social propriety and a bitterly repressive mother. Part of the shock comes from the clash of expectations. The realism of Nicholas Georgiadis's set with its creaking staircase and dusty cacti does nothing to prepare you for the bleak shape-making of MacMillan's choreography, or the vicious twang of Frank Martin's harpsichord-concerto.

These young women don't walk across a room – they creep on their pointes, jealous, suspicious, desperate for escape. At one point they form a neat pile of seated bodies on their mother's lap, a warped inversion of the image of emerging womanhood in the great early modernist ballet Les Noces. A suitor is introduced: a smirking specimen, all balls and no brain. The eldest sister, rigid with nerves, is nonetheless determined to surrender to him, not knowing that the youngest already has.

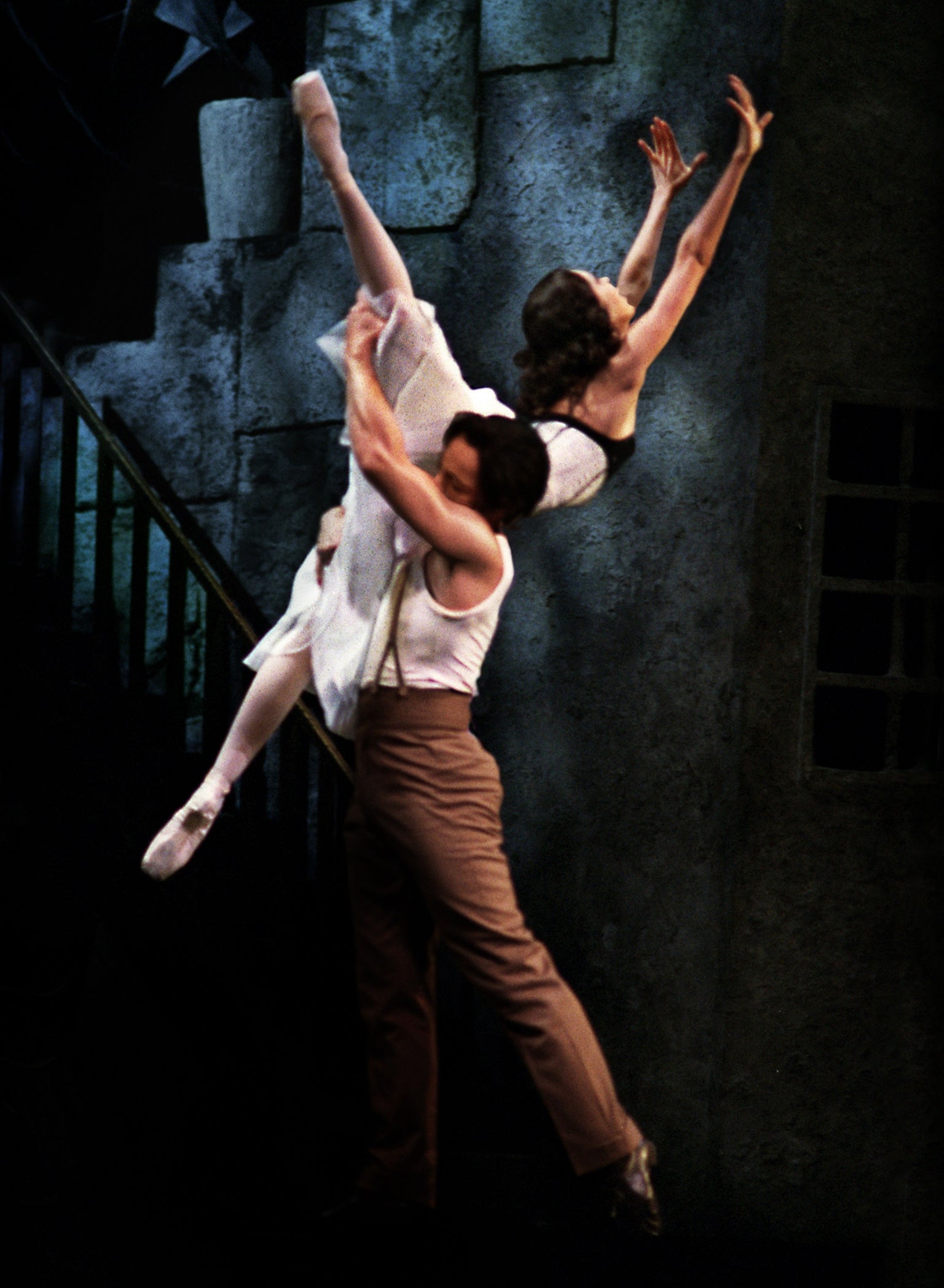

Alina Cojocaru is on searing form as the spinsterish elder sister, Beatriz Stix-Brunell stunning as the burn-in-hell youngest, virtually spatchcocking herself in her abandon with Thomas Whitehead's bonehead of a lover. This is about as nasty as ballet gets, and brutish, not to mention short.

Hard to believe that the other two works on the programme sprang from the same imagination. Concerto, from 1966, is a pure-dance response to a Shostakovich piano concerto whose outer movements zip along without a care in the world. MacMillan divides his cast into three teams decked out in fruit-gum colours, the reds intersecting the orange and lemon teams in great diagonals of joyous leaping. Marianela Nunez and Rupert Pennefather preside over the slow movement with melt-in-the-mouth control.

Requiem, by contrast, is a great cathedral of a piece, sombre in its references (its creation prompted by the sudden death of a close friend) but transporting, whatever your religious position. Gabriel Fauré's luscious setting of the Requiem Mass draws from MacMillan images of surpassing imagination: a cloud of furious shaking fists; women's bodies held aloft and travelled like fleeing souls; a male solo in which a cramped cheek-stand reads unmistakably as a foetus. At one point the dancers simply gather round an intensifying patch of white light into which they disappear, one by one. No choreographer alive today is addressing the big questions of birth, death, being and not being. It's good to be reminded that ballet can do this.

It's good, too, to see England's oldest street-dance forms not just alive and kicking, but devolving. Morris men with their flowers and bells aren't exactly up there with breakdancers as models of cool. But an ambitious new touring show, The Lock In, might just change that.

The inspiration comes from Damien Barber, frontman of the award-winning folk band The Demon Barbers, who supply the floor-shaking live music that alone justifies the price of the ticket. The show opens with the wail of police sirens as three youths – a hip-hop crew in fact – burst into a seemingly deserted pub to escape the law. After strutting their skills-set, they discover they are not alone. The pub's regular clientele includes a trio of female Lancashire cloggers, a longsword and rapper-sword team (not that kind of rapper) and a set of Cotswold Morris men.

At first wary of each other, a keen competitiveness takes hold, aggressive, then increasingly friendly, as each faction finds points to admire in the other. Before long they're sharing and swapping techniques, spurred on by the fiery, beat-driven music, and the plosive blandishments of beatboxer Grace Savage. You'll rub your eyes in disbelief, but stripped of their silly outfits, even the kerchief-waving Morris dances manage to look tough and manly. The Lock In makes for a rousing night out.

Triple bill: (020-7304 4000) to 5 Dec. 'The Lock In': UK tour resumes in February 2013 (thelockindanceshow.co.uk)

Critic's Choice

Birmingham Royal Ballet is nearly always first off the blocks with its Christmas number, and its revival of David Bintley’s glamorous Cinderella production is already packing houses. This is a straightforward take on the story, complete with crinolines, wigs and life-size amphibian coachmen, lizardtails poking from their frock coats. The transformation scene is a dazzler, but the best magic comes from Prokofiev’s darkly glittering score. At Birmingham Hippodrome, to 9 Dec.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments