Giasone, Iford Manor, Wiltshire<br/>Counterpoise, Charterhouse, London

Cavalli is back in fashion again – and on the basis of one stirringly staged, pocket-sized production amid terraces and wisteria vines, he deserves his new fame

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Built in 1914, the cloisters in the Peto Garden at Iford Manor seat only 90 people. Ticket prices for Iford's opera season are high, around £90, though not high enough to cover costs. It should be a place for champagne picnics and corporate entertainment. Instead, it's a place for six-foot-tall lager-drinking rabbits, lustful squaddies, buxom blondes and tour guides welcoming us to Colchis, the "sun, sea and sex resort".

If the terraces and wisteria of Iford suggest a mini-Garsington or Grange Park, its informal atmosphere and shoestring production values are closer to those of Graham Vick's site-specific work with Birmingham Opera Company.

Played in the round in a space scarcely bigger than a generous hotel room, with a gap in the audience for an orchestra of two violins, viola da gamba, theorbo, double-harp and harpsichord, Martin Constantine's production of Cavalli's Giasone for the Early Opera Company offered a sort of Big Brother intimacy, every bead of sweat and smudge of mascara magnified.

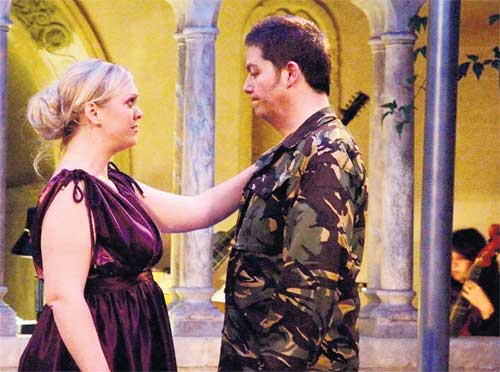

Clad in cruise-crew uniforms, Apollo (Mark Chaundy) and Cupid (Joanne Boag) debate Jason's future while the hero himself (Stephen Wallace) enjoys an energetic tumble with Medea (Madeleine Shaw). A television stands in one corner, a fridge in another, the fixings for Medea's post-coital Bloody Mary – what else? – laid out on its surface. "Weakened by the skirmishes of love", as Ronald Eyre's wry, elegant translation has it, Jason has forgotten his promises to Hypsipile (Sinéad Campbell) and abandoned his quest for the golden fleece.

Cavalli's opera is no action movie. Save for Medea's jagged incantation (which is where the rabbits come in) and the obligatory shipwreck, its subject is erotic obsession, traced in languidly swaying ground-basses, pressing suspensions from the violins, unhurried ariosi and chromatic laments. Although baroque convention demands restoration of order and a dose of comic commentary from a hairy-chested nurse (Rob Burt), a stuttering servant (Nick Sharratt) and a worldly-wise maid (Boag again), the glances between Medea and Jason at the close of this production indicate that their mutual obsession is not over.

That Giasone was once Italy's most popular opera is not hard to believe. Directed from the harpsichord by Christian Curnyn, seamlessly edited down to just over two hours of music, and beautifully played by Oliver Webber, Hannah Tibell, Emilia Benjamin, Richard Sweeney and Joy Smith, this was a musical delight, most especially in the duets and quartets.

Shaw's bright, expressive mezzo and Wallace's masculine, grainy counter-tenor were well matched, their passion believable, their words clear. Burt, Boag, Chaundy, Jonathan Brown (Orestes) and Sharrat offered witty and confident support, Campbell pathos, poise and perhaps a degree of steely passive-aggression Cavalli would not have anticipated from a stock-in-trade tragic heroine.

With a new production of La Calisto coming up at the Royal Opera House, it seems that Cavalli is back in fashion. Can the same be said of the melodrama?

Counterpoise's packed City of London Festival performance featured Liszt's The Sad Monk, Wagner's Gretchen, Strauss's The Castle by the Sea, James Francis Brown's Chapel of Rest arrangement of the Siegfried Idyll for violin, trumpet, saxophone and organ, and a new melodrama by Edward Rushton, On the Edge.

Melodrama thrives on overstatement. Its natural habitat is dark and stormy. Adapted from Sir Arnold Lunn's memoirs by librettist Dagny Gioulami and accompanied by video-artist Syl Betulius's Rorsachian images of climbing figures, On the Edge subverts all melodramatic conventions.

Pizzicato harmonics, muted reports from the trumpet, glancing figures from the piano evoke splintering sunlit ice. Gioulami's arrangement of Lunn's understated descriptions of nearly losing his wife Mabel on their alpine honeymoon is tongue-in-cheek, there are death tolls of various avalanches, and a "voom sound" that signals danger to an alpinist.

Crisply narrated by Eleanor Bron and deftly played by Alexandra Wood, Kyle Horch, Deborah Calland and Helen Reid, On the Edge seemed less a revival of an all-but-extinct musical form than a tribute to an all-but-extinct breed of Englishman.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments