Company Wayne McGregor, Sadler’s Wells, London, review: There’s a new breadth and intimacy to this choreography

McGregor's latest work 'Autobiography', which explores dance and genetics, breaks fresh ground

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

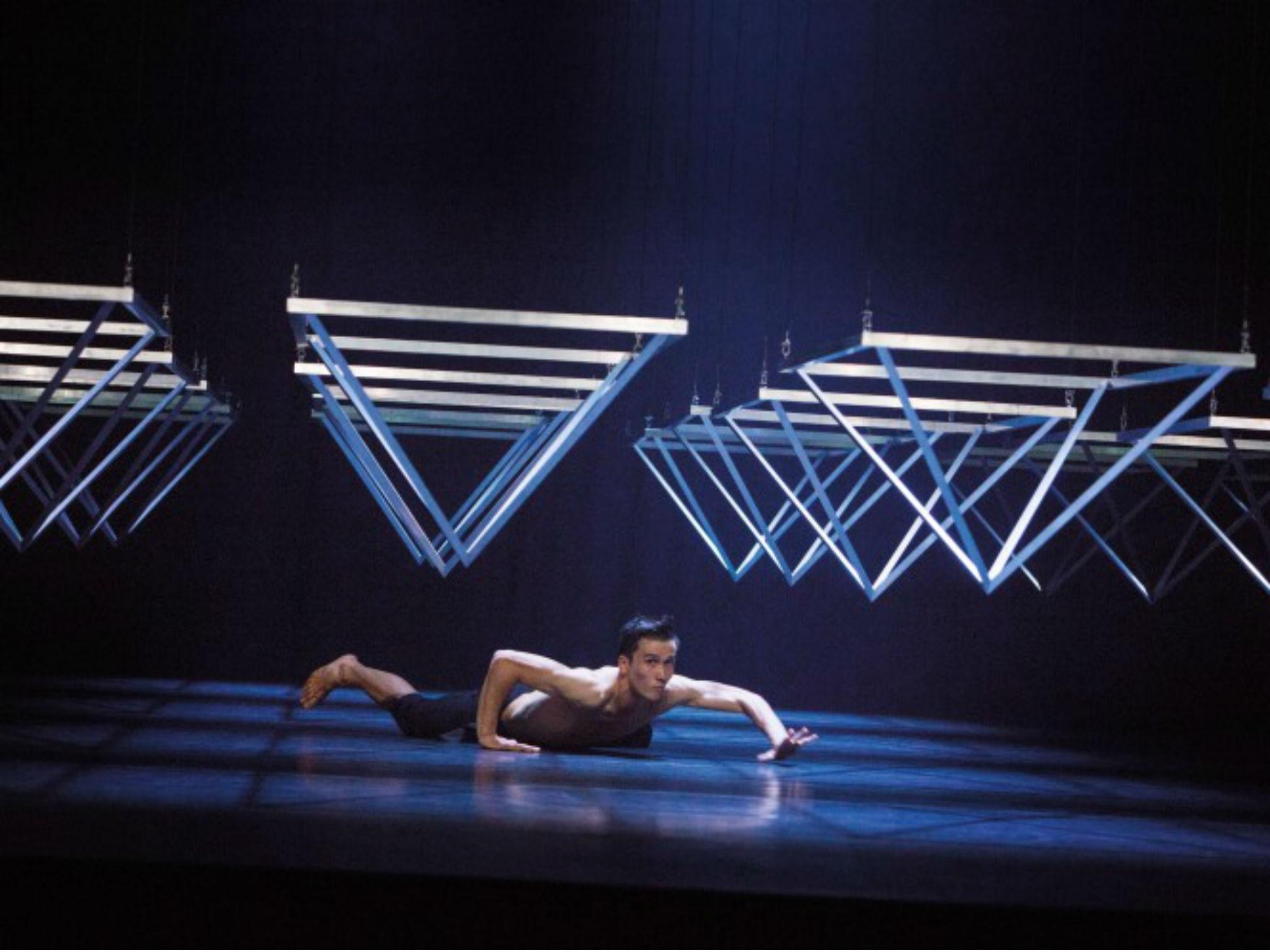

Your support makes all the difference.Titled Autobiography, Wayne McGregor’s latest work deliberately avoids the traditional narrative of life writing. There’s no where-I-grew-up here: instead, abstract dances play out under bright lights. The order is chosen by random selection, shaped by the sequence of the choreographer’s own genome. The elaborate setup has some lulls, but it allows McGregor to break fresh ground. There’s a new breadth and intimacy to this choreography.

In a 25-year international career that has taken him from art collaborations to Harry Potter films, McGregor has always been fascinated by science. His collaborations with neuroscientists, heart surgeons and others have often fed into highly stylised works. The connections aren’t necessarily literal or obvious. Autobiography, the first of a series exploring dance and genetics, is firmly in this tradition, but finds a different emotional range.

As ever, McGregor’s dancers are sleek and swift, but they’re also given space to be individual. Jordan James Bridge has a hip hop flicker to one whirling solo; there’s catwalk flair to Louis McMiller’s strut. In duets and trios, there’s a sense of spontaneity and interaction: tenderness, competition, response.

The framework is stark. Ben Cullen Williams’ set is a bare black stage with a metal network hanging overhead. Lucy Carter’s lighting is striking but aggressive. She makes sculptural use of bright lights and laser beams, including shining them painfully into the audience’s eyes.

The 19 dancers wear black, white and flesh-coloured layers by Aitor Throup, deconstructed neutrals. Surtitles announce the name and number of each randomly chosen sequence. The chance order is a nod to choreographer Merce Cunningham, an acknowledgement of McGregor’s dance influences.

The music, by former steel mill worker Jlin, is a lively mix of industrial sound, dance rhythms and unexpected changes of direction. In one sequence, dancers bring on chairs and sit listening to birdsong. Another is set to stately baroque strings.

McGregor responds with his own variety. There’s much less of his trademark twitchiness, less emphasis on the dancers’ relentless flexibility. This time, there are grand, slow sequences, changes of pace. Dancers have time to colour and shade their steps. Jacob O’Connell leaps boundingly high, then curls through a sumptuously slow bend. One group glance up when Williams’ set lowers, then decide to dive under it. There’s time to breathe, to react. Autobiography may not concern itself with the narrative of McGregor’s life, but it allows its dancers to be personal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments